Language, Power, and the Long Erasure of a Plural Past

Bangladesh’s education system was taken nearly wholesale from the British colonial apparatus. As such, we are encouraged to begin with colonialism and the so-called Bengali Renaissance, only to end there as well. Everything before that, nearly a millennium of political sovereignty, cultural production, linguistic evolution, and social experimentation, is smushed into a few vague references or erased entirely. What remains is a unilinear narrative in which time moves from ancient India to British modernity, in which Muslim rule is figured not as a constitutive phase of Bengal’s becoming but as a civilizational break. This is not an innocent omission. It is a narrative architecture carefully constructed through colonial historiography and later internalized by postcolonial elites. The result is selective amnesia: Bengal is remembered without remembering itself. To understand how this happened, we have to excavate Bengal’s deeper past: its shifting capitals, its changing language, and the political decisions that determined who could speak and write, who counted as members, and who could belong.

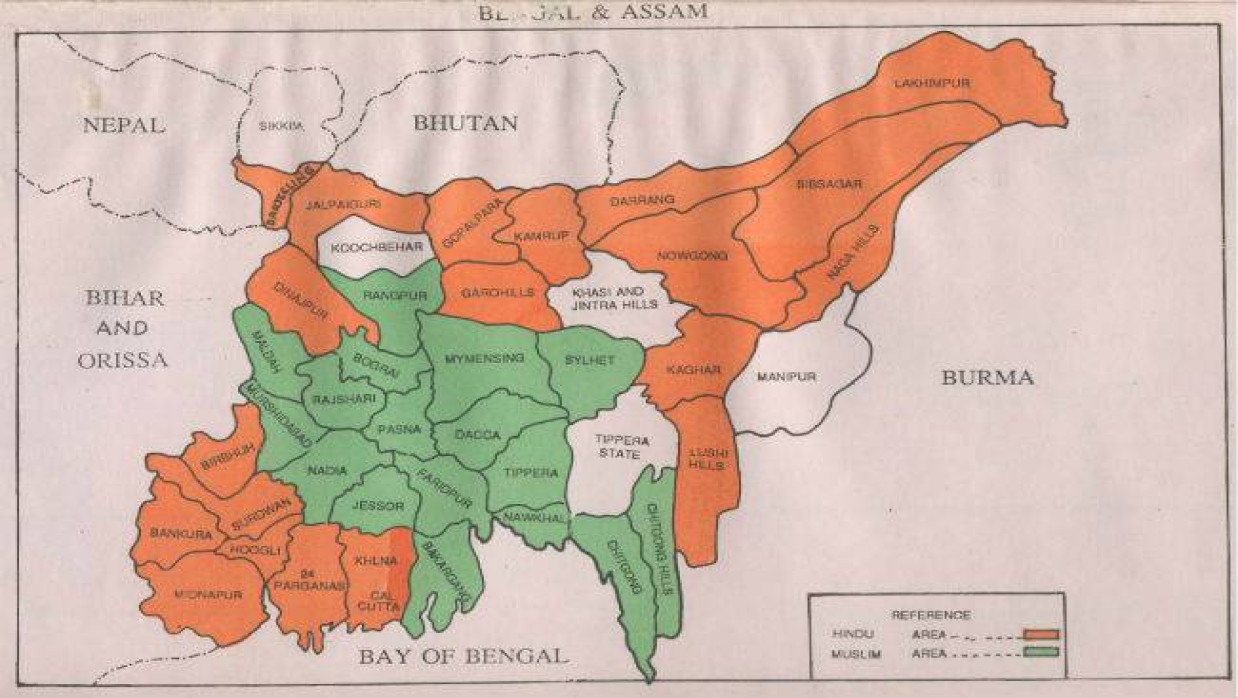

Before Kolkata: The Geography of Power in Bengal

Before Kolkata was established as a colonial metropolis, Bengal had other, older cultural and political capitals. When Kolkata was a swampy sprawl of fishing villages, Dhaka and Murshidabad were major cities full of artisans, traders, scholars, administrators, and political powerbrokers. Dhaka was a cosmopolitan city home to people of diverse ethnic and religious identities, while Murshidabad, under the Nawabs in the eighteenth century, became one of the richest cities in the world. The point is not just antiquarianism. This historical geography matters because it directly undercuts a deeply ingrained assumption in both Bengali and Indian historiography: that modernity and culture, that political and intellectual life, radiated outward from colonial Calcutta. In reality, Calcutta’s ascent in Bengal was a pyrrhic victory that coincided with the engineered decline of older, competing centers of Bengali power and patronage. Colonial histories reversed cause and effect. British rule was cast as the wellspring of Bengal’s awakening rather than the force that displaced and dismantled its indigenous institutions.

Language Before the Nation: The Early Evolution of Bangla

Bangla did not suddenly emerge in the nineteenth century as a fully fledged literary language. It had long roots, stretching back into the first millennium, when a language of Magadhi Prakrit origin passed through Apabhramsa into the early vernacular forms. Buddhist monks, who roamed eastern India from the seventh to the twelfth centuries, composed poetry in an embryonic form of Bangla. Their works were written in verse, but they mixed popular speech with philosophical investigation. These poems later came to be known as the Charyapadas; they are the oldest known examples of Bengali literature. Yet these monks suffered persecution under the Sen dynasty. Sens were orthodox Hindu rulers who ruled Bengal before Muslim sovereignty. They imposed Sanskrit as the only legitimate language of religion and governance. Bangla was profane, vulgar, unfit for sacred or scholarly usage. Translating Hindu scriptures into the vernacular was not just frowned upon; it was criminalized. Chroniclers recount harsh punishments being meted out to those found doing so.

This is a crucial historical irony: the earliest attempt to suppress Bangla as a literary language came not from Muslim rulers but from an elite Sanskritic order anxious to preserve its cultural monopoly.

The Sultani Period: Bengal’s Forgotten Golden Age

Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah and other independent sultans who ruled Bengal between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries presided over a period of extraordinary linguistic and cultural creativity. Far from supplanting local speech with Persian or Arabic, they actively patronized Bangla. Poets, translators, and scholars who wrote in the vernacular received support from the courts, which helped solidify Bangla as a language of literature and public life. It was during this time that Krittibas Ojha, under royal patronage, composed the Krittibasi Ramayan. This was no marginal project. It was the first major vernacularization of the Ramayana into Bangla, and it would become the definitive version for centuries. The text was foundational for Bengali theatre, devotional practice, and literary imagination across religious divides. Think of it: A Muslim-ruled court sponsored the translation of a Hindu epic into the local language, making it accessible to ordinary people. This alone shatters the persistent but entirely specious claim that Muslim rule was inherently hostile to Bengali culture. We can go further.

Patronage, Not Persecution

The sultani period was also the age of Mangalkavya, Vaishnava poetry, baul/brittany songs/narrative ballads with an admixture of Islamic/Hindu/local folk elements. Arabic and Persian chronicles from the period also enthuse over the beauty of Bangla, while inscriptions show a multilingual polity in which Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, and Bangla coexisted. It was not secularism in the modern sense, but it was pluralism in practice. Power did not require cultural homogenization. Instead, legitimacy was manufactured through accommodation and patronage.

That this period is barely mentioned in school curricula and standard historical accounts is telling. Its memory, its very existence, upends the neat binaries of colonial history.

The Nalanda Myth and the Politics of Blame

One of the most persistent stories used to depict Muslim rule as barbaric is the claim that Ikhtiyaruddin Bakhtiyar Khilji destroyed Nalanda University, burning its vast library and extinguishing Buddhist learning in the region.

But the story doesn’t hold up. There’s no mention of it in contemporaneous sources. Archaeology doesn’t show a sudden, complete annihilation. In fact, Nalanda was in decline long before the raids, as donations dried up and trade routes shifted. The accounts that do mention it come centuries later, embellished to fit a satisfying narrative arc: Muslim invasion as civilizational disaster.

The myth endures because it’s so easily weaponized. History is pressed into service against contemporary insecurities. Stories that confirm our ancestral biases get retold. And the facts get quietly discarded.

Colonialism and the Reinvention of the Past

British administrators and scholars played a decisive role in reframing Bengal’s history. By elevating the Bengali Renaissance, a movement centered largely among upper-caste Hindu elites in Calcutta, they presented colonial rule as a catalyst for enlightenment. Everything before was cast as stagnation.

This was not accidental. A narrative that portrayed Muslims as destroyers and Hindus as natural allies of British modernity helped stabilize colonial control. It also justified the dismantling of Muslim-led institutions and the redistribution of land and power.

Over time, this historiography was internalized. Bengal’s past was taught through colonial lenses, even after independence.

Literature, Secularism, and the Problem of Exclusion

Colonial-era Bengali literature, for example, mirrors this narrowing of the cultural imagination. Muslims figure in it only rarely. When they do, they are more likely to be caricatures: either rustic buffoons or symbols of feudal backwardness. At the other extreme, a secularism developed that defined itself by erasing religious difference rather than by a pluralist embrace.

“Bengali” became not just a linguistic but also a moral and aesthetic category, implicitly (or sometimes explicitly) coded as Hindu. Muslim lifeways, rituals, and intellectual traditions were thereby placed on the margins, if not cast as incompatible with Bengali life.

Atheism and humanism had their place in this world. But secularisms that fully accounted for Islamic worldviews as a constitutive element of Bengali life were rare. The upshot would be a profound political alienation in the century to come.

Language as a Site of Power

The history of Bangla literature cannot be written without asking certain questions of power. Who writes? Who gets patronage? Which texts are preserved, and which are forgotten? The answers have always had less to do with language than with politics.

Under Muslim sultans, Bangla expanded because it was patronized. Under the Sens, it contracted due to oppression. Under the British, it was appropriated and recast to serve a new colonial public sphere, centered in Calcutta.

To make these points is not to romanticize any age, but only to insist on historical honesty.

Recovering Bengal’s plural past is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is a necessary step in coming to terms with who we are and who we have been taught to forget. Only when we acknowledge the full arc of Bengal’s past can Bangla truly belong to all of us who speak it.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published