By Shweta Desai

By Shweta Desai

Shaukimal Prajapati is a Pakistani Hindu who has found shelter in India, but never succeeded in finding a place that he could truly call his home.

“I am a Hindu in Pakistan, but a Pakistani in India,” the MSc graduate from Pakistan’s Sindh Agricultural University, laments.

Prajapati’s plight embodies the adversity that is commonly experienced by thousands of Pakistani Hindus like him, who have fled perceived persecution and harassment to take refuge in Hindu-majority India, only to be rebuffed and treated with suspicion.

Hindus form the single largest minority in Pakistan, accounting for 1.6 percent of its total population of about 180 million. About 95 percent of Pakistan’s Hindu population is concentrated in its southern provinces of Punjab and Sindh.

However many have complained of being targeted and discriminated against. Hindus in Pakistan say they are subjected to abductions for ransom, rape, forced religious conversions and even forced marriages of young girls.

“I was a Hindu in a Muslim country and there was no space for my future there,” explains Ramesh Pawar, 32, who some three months ago packed his suitcases and left his ancestral home in Pakistan’s Karachi with his family to take the cross-country Thar Express train to India.

In recent years, the exodus of Hindus from Pakistan has reportedly accelerated and India’s border state of Rajasthan is one of their favourite destinations. There are now about 400 refugee settlements in cities like Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Bikaner and Jaipur.

The four-hour journey to India by the Thar Express train is increasingly being viewed by many Pakistani Hindus as a passport to a secure career and a better future.

Ashok, a social worker, is a recent arrival from Pakistan. Unlike many others, he had a stable job back home. Yet, he felt insecure and left. “There was a huge risk of survival every night as a minority. [I] didn’t feel safe to leave [my] wife and kids at home, while working outside,” he says.

Assad Iqbal Butt, a member of the Human Rights Commission Pakistan (HRCP), an independent body campaigning for human rights, says that Hindus face increasing hostility in Pakistan.

“The Hindus in Sindh are largely traders, businessmen and landlords. By targeting them for ransom with death threats and abductions, forceful conversions and marriages, the extremists are able to spread fear and drive them to migrate, thus taking over their houses and business.”

Butt felt there was a “collective fear and collective silence”. He said the situation of the Hindu community was so dire that people lived in perpetual threat.

“When the state itself has failed to protect the rights of its own people, who dare to stand for the minorities, what hope does the minorities themselves have? What will they do if not flee,” he asks.

Emails to the Pakistani embassy in New Delhi for an official response received no response.

According to HRCP, religious intimidation against Hindus has caused both internal displacements from the Frontier Provinces and Balochistan to the cities around Karachi and Hyderabad, and external migration which saw around 600 to 1,000 families in 2012-2013 flee to India.

Birth of two nations

According to Seemant Lok Sanghatana, a Rajasthan-based organisation fighting for the rights of Pakistani Hindu immigrants, almost 120,000 Pakistani Hindus are now known to live in India, and approximately 1,000 migrate annually to Rajasthan alone in the hope of securing Indian citizenship.

Those fleeing mostly travel with valid documents and visas.

“Yes, they are coming with an intention to not go back, but they are returning to their land of forefathers,” says Hindu Singh Sodha, who himself undertook a gruelling 50km horse ride in 1971, to cross over into India.

He was fleeing increased persecution at a time when the two countries fought a bitter war that led to the bifurcation of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

But animosity towards religious minorities dates back even further. Since the British left India in 1947 – dividing the land into Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India – minorities on either side have often felt unwanted and unwelcome in the land of their birth.

Hindus, for example, in the border regions of Punjab and Sindh woke up to find themselves as Pakistanis.

“They have become victims of the hostility of the India-Pakistan relations,” said HRCP’s Butt.

|

But fleeing hatred and suspicion just by crossing international boundaries is easier said than done.

India refuses to recognise fleeing Pakistani Hindus as “refugees”. According to the 1951 Refugee Convention, a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality is taken into consideration to define a refugee.

India, however, is not a signatory to the convention.

And though India offers assistance to asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Somalia and Sudan, the same option is not extended to those from Pakistan.

Attempts to get a response from the Indian Ministry of External Affairs on the issue failed with emails being ignored.

“There is no intervention by the Indian government or international agencies for the plight of Pakistani Hindus,” complains Sodha.

A refugee status would have helped Hindus from Pakistan to acquire residence permits and find employment.

In its absence, they are forced to wait for seven years before they can apply for citizenship under the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955.

Until 2005-06, about 13,000 Pakistani Hindu migrants staying in Rajasthan had been granted Indian citizenship. The numbers have dwindled in the last three years though, with only 915 being granted citizenship.

So having crossed over into India and with no intention of returning home, the sole identity for many continues to be, ironically, their Pakistani passports. And on its expiry, they become stateless citizens.

“They have become victims of the hostility of the India-Pakistan relations. In Pakistan, they are targeted because they are Hindus and in India they are vulnerable because they are Pakistanis,” says HRCP’s Butt.

Prajapati, who fled Pakistan, experiences such vulnerabilities on a daily basis. “We somehow feel stranger here. When our nationality is revealed, there is a change in people’s attitude.”

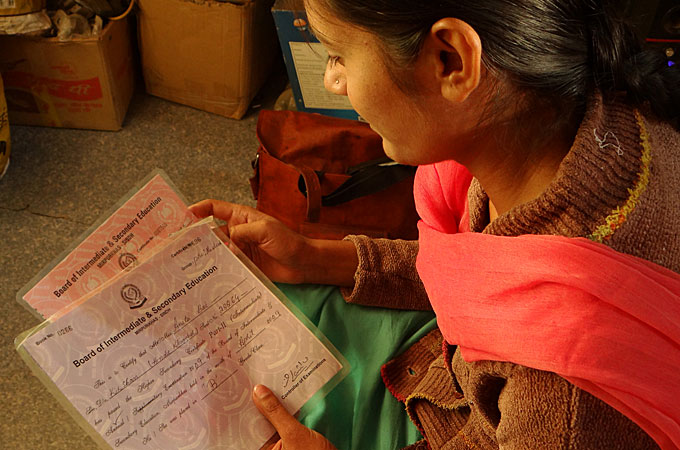

Sunita, his young niece, who migrated to India in 2012, had completed a year studying in the Maulana Azad Institute of Pharmacy in Jodhpur when her admission was cancelled a day before her examination.

“I was told that my secondary school certificate from Sindh Pakistan is not recognised in India, I won’t find admissions for studies here.”

Pawar, who came three months ago, is also finding the going tough in India.

“I am qualified enough to work on my merits in India, but no one is willing to hire me once they know I am from Pakistan,” he says.

“My life was dark in Pakistan where I had to hide my identity as a Hindu. And now in India, my life continues to be in darkness as I have to hide I am Pakistani.”

*Some names have been changed to protect the identity of interviewees.

source : aljazeera

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published