Speaking at the inauguration of India’s first dedicated military university in May 2013, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh saw his country “well positioned to become a net provider of security in its immediate region and beyond”. While no particular emphasis was put on the word “beyond”, it is apparent that the Indian military’s security footprint is expanding beyond the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) with specific exercises being conducted to protect Indian overseas energy assets in areas like the South China Sea (SCS). In fact, Indian strategic community seems rather comfortable with the emerging coinage Indo-Pacific that sees the Indian and Pacific Ocean theatres as a continuum and is acquiring out of area capabilities such as aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines that would allow it to project credible force throughout this consolidated sphere.

However even as Indian security thinking catches up with its extending geo-economic interests, the fact remains that India continues to be flanked on its main land borders by two nuclear armed rivals, Pakistan and China, who describe their friendship as “taller than the tallest mountains and deeper than the deepest seas.” The Sino-Pakistani nuclear relationship shows no signs of abetting and there are deep suspicions in New Delhi with respect to potential coordination between the two countries in military operations along India’s northern frontiers in Kashmir. Moreover border incidents between India and Pakistan and India and China have multiplied in recent times and in 2009, the Minister of Defense formally asked the Indian Armed forces to prepare for a two-front scenario.

That India sees itself as a “net” provider of security is in itself reflective of its civilian leadership retaining the option of undertaking punitive operations across its frontiers and indeed in the Indian Ocean against enemy sea lines of communication (SLOC). Such a situation can come to pass in the event of another 26/11 style attack by terrorist elements based in Pakistan or if say a 2013 Depsang like intrusion by China refuses to be winded down via negotiations. Indian military planning in recent years therefore predicates itself on creating the ability to carry out simultaneous offensive conventional operations against both Pakistan and China against a nuclear backdrop.

Indeed India has moved from a “defence” to a “deterrence” posture with respect to China as well in addition to its similar longstanding posture (i.e. deterrence) against Pakistan. In the event of a two-front war Indian forces will no longer merely look to “hold” Chinese forces as they concentrate offensive elements against the Pakistanis before switching forces from West to East following a collapse of Pakistan’s defenses.

This Indian doctrinal shift vis a vis China ultimately stems from failed attempts at enduring détente between the two sides since 2003 when a National Democratic Alliance (NDA) ruled India recognized the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) as a part of China in return for the latter dropping Sikkim from its list of territorial claims. The United Progressive Government (UPA) has sought to carry forward this legacy by engaging Beijing in continuous dialogue since it took power in 2004.

But after the 2005 Bush-Singh nuclear accord, the Chinese began upping the ante on the diplomatic front with respect to territorial disputes with the Chinese Ambassador to India publicly stating in 2006 his country’s claim over the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and not just Tawang as was widely believed to be the Chinese position till that time. The subsequent period has seen a major increase in Chinese “transgressions” across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) leading up to a bloodless Chinese Army intrusion in April 2013 which penetrated into Indian held territory far beyond even the current Chinese claim line in the Ladakh region.

This period has also been marked by a rapid build-up of dual use infrastructure by the Chinese on the Tibetan Plateau besides the Chinese military undergoing massive conventional force modernization. From the Indian perspective the new infrastructure allows the Chinese to build better equipped forces far more rapidly and at multiple points than ever before. Indeed heightened Chinese activities on the LAC derive from the new “last mile connectivity” that they now have on various points along it.

The Indian Army(IA) which earlier had a thought process of keeping its own side of the LAC a wilderness so that ingressing forces simply overextended their supply lines, now feels that the Chinese have built up enough supporting frontier infrastructure to move in much deeper and at multiple points before they get bogged down. Moreover, the new infrastructure on the Chinese side is actually allowing them to launch patrols all the way to their claim line and beyond in what is Indian held territory with a view to perhaps extending their LAC road networks even further.

India therefore has been upgrading its own LAC infrastructure in recent times to both prevent the Chinese from nibbling away at territory by being able to orchestrate counter patrols, as well as laying the back end support enablers for mounting its own offensives into the Tibetan Plateau if required. The IA believes a defensive battle against quickly concentrated Chinese forces at a point chosen by the latter is an inferior alternative to mounting a counter offensive of its own at a time and place of its choosing with a view to grabbing Chinese held territory that can later be used as bargaining chip in negotiations.

Besides the investment in new border road networks (progressing too slowly for most critics), strategic tunnel projects, re-activated airbases and advanced landing grounds this shift in mindset has also manifested itself in the May 2013 Cabinet go ahead to the IA’s first ever dedicated Mountain Strike Corps (MSC) based in Panagarh in the Eastern Indian state of West Bengal. Significantly, the final nod for the $10-12 billion spend spread over the next 7-8 years for raising this new formation was given right after the Depsang intrusion took place. The large outlay for the MSC represents not only manpower costs since the IA is adding new personnel strength after a long hiatus but also specific equipment costs related to the acquisition of integral heli-lift capable artillery, aviation assets and tactical missile firepower suitable for use in a mountainous environment that constitutes in the main India’s de facto border with China.

The MSC for some represents a return of “threat” orientation in military force planning since it involves not just standard conventional force modernization but the incurring of significant multi-year liabilities for force component accretion seemingly dovetailed to a specific context. In the new millennium Indian military writing has often talked about graduating from a “threat” oriented security system that concentrates on a large scale ground war against Pakistan in the plains to one that looks to bring in new “capabilities” in terms of platforms and training that have the flexibility to cater to a range of threats some of which might just be emerging.

Unsurprisingly, the Indian Navy (IN) which prides itself on “capability” based planning has been rather strident in its opposition to the setting up of the MSC since it has seen its raising as a threat to its own plans for expanding its capital acquisition budget in a period when the Indian defense budget has somewhat stagnated in dollar terms on account of a weak rupee. The overall defense budget itself which stands at $37.16 billion (at current rates) for 2014-15 (interim) has stayed well below 2 percent of Gross Domestic Product for the last few years.

The IN long described as India’s Cinderella service came into its own in the first decade of the 21st century beginning around the time when NDA Defense Minister George Fernandes overtly announced in 2001 that the Indian government had made the development of India’s Navy a strategic priority. Once again this policy was carried forward by the UPA government as well and today the IN operates stealth destroyers and frigates of Indian and Russian origin, an Akula-II class nuclear attack submarine, INS Chakra, leased from Russia, an ex-US Navy Landing platform dock, two aircraft carriers (ACs) with the recent delivery of the INS Vikramaditya by the Russians, and a soon to be operational domestically built ballistic missile nuclear submarine, INS Arihant. Three more follow-ons to the INS Arihant are in various stages of construction and India’s first indigenously built AC, INS Vikrant, was launched in 2013 with delivery aimed for 2017.

The IN which sees itself as a key protector of Indian overseas interests believes that a country (i.e. India) whose trade is overwhelmingly seaborne (about 95 percent) and is pursuing a global strategy for energy and food security must embrace a much deeper oceanic approach to its security planning. With China increasing its strategic petroleum reserves to over a 100 days of self-sufficiency in the event of conflict, the IN probably realizes that mere interdiction of Chinese SLOCs in the IOR will not suffice as a deterrent to the Chinese Navy moving against Indian interests in the SCS.

Active protection of Indian assets in faraway seas and the ability to project power in the Chinese littoral has now emerged as part of its scenario planning. Indeed the advocacy by retired navy thinkers close to the government for acquiring a bigger nuclear submarine force (both SSNs and SSBNs) than what currently seems on the anvil clearly supports such a view. The emphasis on nuclear submarines is understandable since such boats have both the endurance and stealth required for fighting in distant seas characterized by enemy anti-access/anti-denial (A2/AD) networks such as the ones being built by the Chinese in the SCS.

But platforms such as nuclear submarines do not come cheap and involve back end infrastructure in the form of extremely low frequency (ELF) communication networks in addition to satellite based battlespace management systems such as the recently launched GSAT-7 which is the IN’s first dedicated satellite. Moreover the IN also has in progress extensive surface fleet augmentation plans in the form of larger and more capable destroyers and frigates, new LPDs, anti-submarine warfare (ASW) corvettes in addition to a projected doubling of the number of aviation assets under its control.

In the last three years the Indian economy has registered far more modest growth rates than it did in the first decade of the new millennium even as the UPA government indulged in a raft of populist policies to shore up its electoral prospects while trying to keep the overall fiscal deficit under control. This has left far less room for capital expenditure growth in the Indian defense budget leading to tussles within the military centered on the semantics of threat versus capability oriented planning. The decline of the rupee vis a vis the dollar in the same period has naturally not helped matters either with the total capital spend available to the military—though greater in rupee terms—has stagnated around the $15 billion mark on an annual basis in the last few years even as all three services continue to be import dependent to various degrees.

This is particularly true of the Indian Air force (IAF), the most import heavy service and one that has consistently garnered the largest share of capital expenditure in the defense budget. Indeed the Army-Navy discord ultimately stems from the fact that the capital expenditure on the IAF is veritably sacrosanct since India depends greatly on airpower capability to deal with its two primary military rivals. In 2011, the government actually cleared the raising of the IAF’s sanctioned combat aircraft strength from 39.5 squadrons to 42 precisely to cater to the demands of a two front scenario. In fact, both India’s biggest weapons import plan as well as joint international development project are for the IAF, being the multi-role medium range combat aircraft (MMRCA) tender (for which the Dassault Rafale has been shortlisted) and the Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft (FGFA) program with Russia respectively. The MMRCA contract is expected to be worth up to $15-20 billion.

The IAF of course also sees itself as a “capability” based force and could argue that its recent acquisitions can be used for a variety of scenarios. For instance the C-130s and C-17s being purchased from the United States via the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) route and the Mi-17 medium helicopters being brought in from Russia are being used for both forward deployment along India’s mountainous borders, while India’s road and rail infrastructure catches up, as well as to support deployments in new bases in the Andaman and Nicobar (A&N) Islands which can host fighters that would provide additional air cover to Indian fleets in the IOR. In fact the IAF seems to have extricated itself from threat vs capability debates to an extent since it often flies in support of the other two services and exercises jointly with the IA and IN more than they do with each other.

Indian strategic thinking does seem keen to leverage the flexibility of airpower and drawing a direct lesson from American campaigns since 1990 has pushed the IAF towards taking the initiative in transformative concepts by leveraging the digital age to bring in cutting edge Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance (C4ISTAR) technology. Subsequently, the pursuit of superior “situational awareness” has been embraced by the other two services as well such as the IN’s Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) concept and the IA’s Battlefield Management System (BMS) project.

Now although the initial acquisitions in the C4ISTAR domain have been from abroad, such as the three PHALCON AWACS the IAF brought from Israel, it is clear that future “transformation” of the Indian military in addition to standard force modernization must be done through indigenous sources both from an affordability as well as a security standpoint given increasing concerns about electronic components originating from China and elsewhere. Indeed one way out of inter-service battles for allocation in periods of budgetary tightening would be much greater focus on indigenization to extend Indian defense rupees as it were.

The UPA’s last Defense Procurement Procedure (DPP-2013), issued at a time when the government was straddled by a host of defense related scams, made for the first time various types of indigenous procurement categories explicitly preferred over buying global. This also meant that it was now mandatory for every procuring service to justify any move to buy overseas. A 30 percent component indigenization clause on a cost basis for any and every piece of equipment was also introduced in DPP-2013. This was done to leverage various offset requirements that have been in place for overseas buys.

While DPP-2013, would seem to signal a decided shift towards favoring indigenization the fact remains that the immediacy of operational requirements, insufficient defense industrial base and corruption has hamstrung the pace of indigenization thus far and India’s private industry is looking for more than just official reassurance for indigenous preference in defense contracts.

Attracted by India’s substantial military modernization spend, its private sector has been looking to grow its defense practice as a lucrative hedge to downturns in the civilian sector. Domestic industry is particularly keen on over 150 “buy and make” (Indian) contracts which allow Indian companies to bring in foreign technology partners and involve competitive trials between prototypes developed by down-selected development agencies with 80 percent of the cost of prototyping borne by the government. However, though greatly touted by the UPA two flagship buy and make Indian programs, the Tactical Communication System (TCS) and Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) have both seen numerous delays with the former getting off the ground only recently.

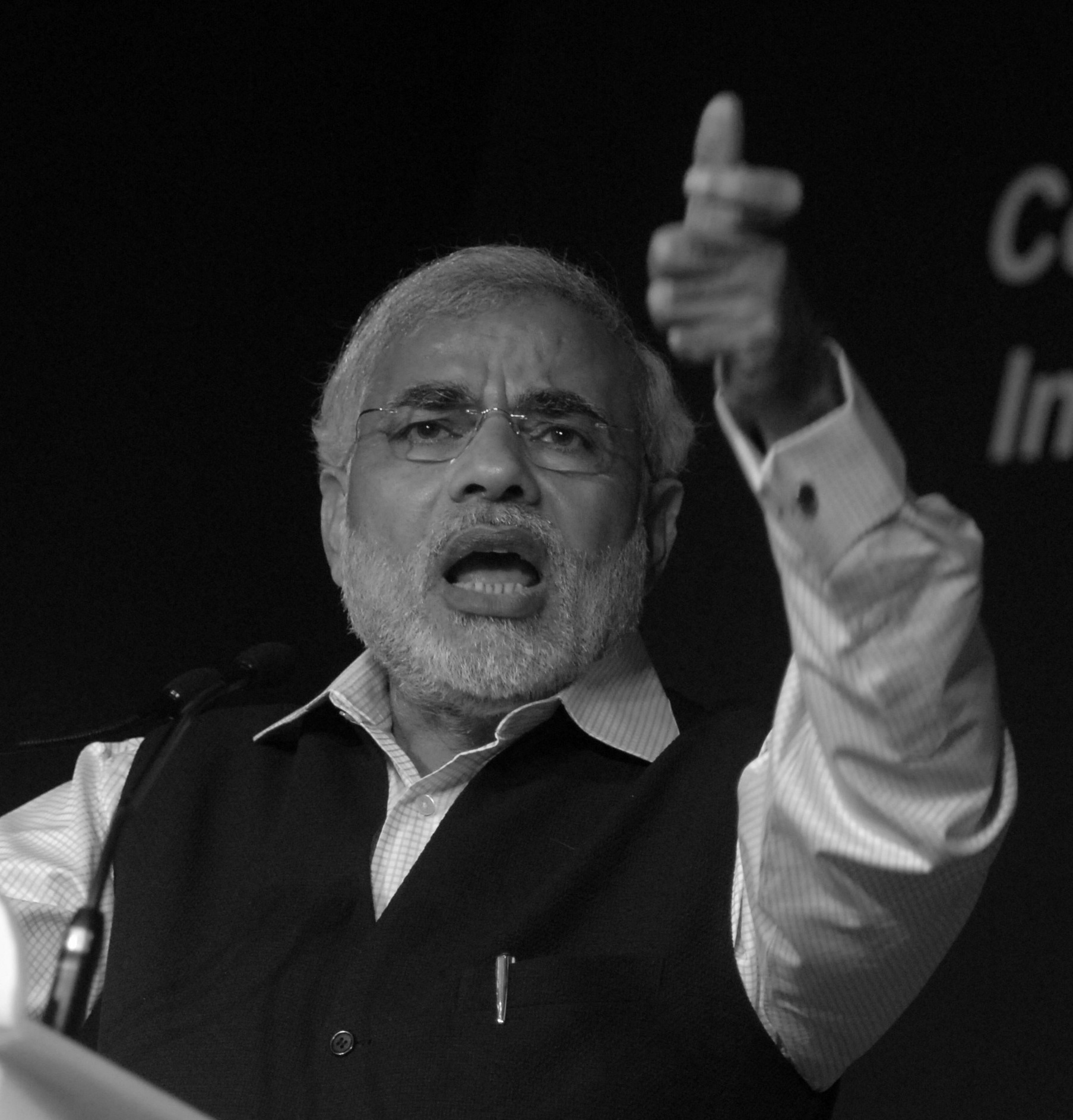

These are precisely the kind of bureaucratic delays that a Narendra Modi led NDA coalition is expected to remove in the perception of industry. Modi has publicly stated not just defense indigenization as a goal for an administration headed by him but defense exports as well. It seems that in Modi’s scheme of things defense indigenization is not just a matter of self-sufficiency in a critical sector but an engine of growth for the economy – a viewpoint emphatically supported by industry which enthusiastically accompanied the Defense Research and Development Organization’s (DRDO) to ADEX-2013 in Seoul, where it made the first ever international exhibition of its wares.

It is worth noting that private sector capabilities in defense have been built in great measure through participation with DRDO in two areas where India has achieved a notable degree of indigenous proficiency — strategic missile systems and electronic warfare (EW). In the coming decade DRDO is keen to make its mark in a range of tactical missile systems both independently as well as by leveraging technology partnerships with foreign entities. Examples of the latter would include the Long Range Surface to Air Missile (LRSAM) project with Israel and the Short Range SAM (SRSAM) project with MBDA of France. The successful Indo-Russian Brahmos missile joint venture provides a sort of template in this sphere although DRDO is keen to partner with private sector players for productionizing these developments.

Also like the Brahmos, which is already in service with the IA and IN with an air-launched version being progressed for the IAF, many of these new tactical missiles will be universal in nature with tailored versions finding their place in the inventories of all three services. Indeed indigenous R&D in India is also leading to several joint developments which in turn are helping reduce the friction over capital expense allocations by leveraging economies of scale. Beyond missiles, this is also visible in the aerospace and EW domains.

Indigenous R&D is now being prioritized as a capacity building exercise that can lead to the capabilities needed to counter emerging threats, such as in the cyber domain. In fact, India is embracing the so-called new triad of cyber, space and special forces with each expected to get a dedicated joint service command of its own. The IAF which has been looking to become an aerospace power is expected to lead space command, the IN will take the lead in building the cyber command and the IA which has the largest number of special force operators will spearhead the new consolidated special operations command (SOC). Besides specific operational elements these new commands are also expected to expedite the development of new technology in these realms.