By:

This article is condensed from a longer paper, available for download here.

Since summer of 2017, troubling reports in Western media outlets about large-scale detentions of ethnic Muslim minorities (including Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz) in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have multiplied (RFA, May 4). These reports include substantial anecdotal and eyewitness evidence describing a network of clandestine “re-education camps” in which detainees can be held indefinitely without process or recourse (AP News, December 17, 2017; Wall Street Journal, December 19, 2017).

The existence of these camps is denied by the Chinese government. In February of this year, during an interview with the Almaty Tengri News, Zhang Wei, China’s Consul General in Kazakhstan, issued what is to date the only statement by a Chinese public official on the reputed camp network. In reference to a CNN report on the camps, Zhang argued that “we do not have such an idea in China” (AKIpress, February 7; CNN, February 3). This article demonstrates that there is, in fact, a substantial body of PRC governmental sources that prove the existence of the camps. Furthermore, the PRC government’s own sources broadly corroborate some estimates by rights groups of number of individuals interred in the camps. While estimates of internment numbers remain speculative, the available evidence suggests that a significant percentage of Xinjiang’s Muslim minority population, likely at least several hundred thousand, and possibly just over one million, are or have been interned in political re-education facilities.

Overall, it is possible that the region’s re-education system exceeds the size of China’s entire former “education through labor” system that was officially abolished in 2013. The article also examines the evolution of re-education in Xinjiang, empirically charting the unprecedented re-education drive initiated by the region’s Party secretary, Chen Quanguo. Information from 73 government procurement and construction bids valued at around RMB 680 million (approximately USD 108 million) along with public recruitment notices and other documents provide unprecedented insights into the evolution and extent of the region’s re-education campaign.

The Inception of “De-Extremification” through Re-Education in Xinjiang

The concept of re-education has a long history in Communist China. In the 1950s, the state established the practices of “reform through labor” (劳动改造) and “re-education through labor” (劳动教养). [1] Later, in the early 2000s, the government initiated “transformation through education” (教育转化) classes for Falun Gong followers. [2]

It was not until 2014 that the “transformation through education” concept in Xinjiang came to be systematically used in wider contexts than the Falun Gong, Party discipline or drug addict rehabilitation. Its application to Uyghur or Muslim population groups arose in tandem with the “de-extremification” (去极端化) campaigns, a phrase first mentioned by Xinjiang’s former Party secretary Zhang Chunxian in 2012 (Phoenix Information, October 12, 2015).

In 2014, the re-education system started to evolve into a network of dedicated facilities. Konashahar (Shufu) County (Kashgar Prefecture) established a three-tiered “transformation through education base” (教育转化基地) system as part of its “de-extremification” efforts (Xinjiang Daily, November 18, 2014). It operated at county, township and village levels. A three-tiered re-education system based on these three levels is likewise mentioned in a 2017 government research paper described below, one whose ideas have apparently found widespread adoption (Harmonious Society Journal via www.doc88.com, p.76, June 2017).

The year 2015 also saw the first media report stating the actual capacity of a centralized re-education facility. Khotan City’s “de-extremification education and training center” (去极端化教育培训中心) was said to hold up to 3,000 detainees whose thinking was “deeply affected” by “religious extremism” (Communist Party News, October 17, 2015).

Chen Quanguo Puts Re-Education into Overdrive

In August 2016, Chen Quanguo became Xinjiang’s new Party Secretary. He came into the job from a position as Party Secretary of Tibet, where he pacified the restive region through a combination of intense securitization and pervasive social control mechanisms (China Brief, September 21, 2017).

A number of separate reports place the onset of massive detentions among the Uyghur population soon thereafter, in late March 2017 (RFA, January 22). This timing coincides neatly with the publication of “de-extremification regulations” (新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例) by the government of the XUAR (Xinjiang Government, March 29, 2017). Directive No. 14 in Section 3 of this document states that “de-extremification must do transformation through education (教育转化) well, jointly implementing individual and centralized education”.

A potentially influential document in this development was a research paper published by Xinjiang’s Urumqi Party School (Harmonious Society Journal via www.doc88.com, June 2017). The paper recommends the creation of “centralized transformation through education training centers” in all prefectures and counties. It lists three types of re-education facilities: “centralized transformation through education training centers” (集中教育转化培训中心), “legal system schools” (法制学校), and “rehabilitation correction centers” (康复矫治中心). Government construction bids confirm this and indicate that these are sometimes part of large new compounds that also host criminal detention centers, police stations or even hospitals and supermarkets (see Table 1).

In May 2017, the first official recruitment notices related to re-education appeared, although evidently most staff were recruited by other means. Karamay, a city in northern Xinjiang, listed 110 re-education center positions for four different “centralized transformation through education classes” (集中教育转化班) as well as 248 police officers for police stations and “transformation through education bases” (教育转化基地) (Zhonggong zhaojing, May 20, 2017; Zhonggong wangxiao, May 20, 2017). Lop and Yutian Counties in Khotan Prefecture advertised “transformation through education center” (教育转化中心) teaching positions (Shiye Danwei Zhaopin, August 2, 2017). Staff and teacher recruitment notices for Xinjiang’s numerous new “educational training centers” (教育培训中心) often required no specific degree, skill, or teaching background. Instead, they frequently preferred recruits who demonstrated strong ideological conformity, army or police experience, or called for “training center policing assistants”. In many instances, training center and police staff recruitments shared the same job posting, and bids show that “training center” compounds often have police stations. [3]

The Costs and Design of Re-Education Facilities

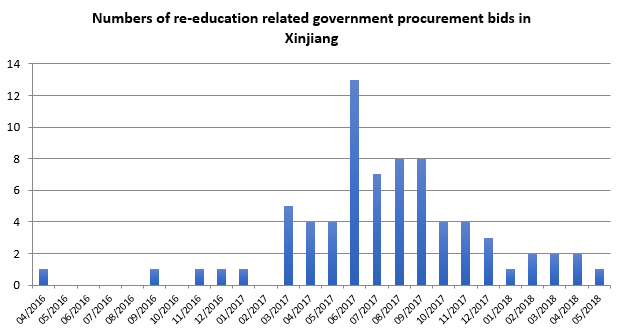

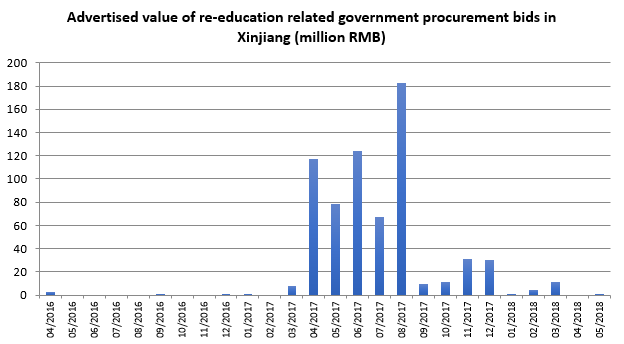

The start of Chen Quanguo’s re-education initiative correlates closely with the release of detailed information in the form of government procurement and construction bids (采购项目 and 建设项目). Nearly all bids were announced from March 2017, just prior to the re-education drive (Figure 1, based on Table 1). Likewise, the values attached to these bids were by far highest in the months immediately after the start of the re-education campaign (Figure 2). While only a fraction of re-education facility construction is reflected in these bids, they do indicate a pattern consistent with re-education policy and implementation.

Figure 1. Source: Government procurement bids (Table 1)

Figure 2. Source: Government procurement bids (Table 1). Values for some projects were not available. For others, advertised values pertained to the construction of several different facilities. In the latter cases, values for re-education facilities were estimated.

Bid descriptions indicate both the construction of new as well as upgrades and enlargements of existing re-education facilities (Table 1). Some pertain to adding sanitary facilities, warm water supplies and heating or catering facilities, indicating that existing buildings are being used to house more people for longer periods of time. Several planned facilities feature compound sizes exceeding 10,000sqm. One bid combines vocational training and re-education facilities totaling 82,000sqm. A former detainee estimated that his re-education facility held nearly 6,000 detainees (RFERL, April 26).

Many bids mandate the installation of comprehensive security features that turn existing facilities into prison-like compounds: surrounding walls, security fences, pull wire mesh, barbwire, reinforced security doors and windows, surveillance systems, secure access systems, watchtowers, and guard rooms or facilities for armed police. One bid emphasized that its surveillance system must cover the entire facility, leaving “no dead angles” (无死角). Several facilities branded as vocational or other educational training facilities also carried bids calling for extensive security installations, with some mandating police stations on the same compound.

Overall, documentation assembled by the author lists 73 re-education facility related procurement bids valued at RMB 682 million in respect to their re-education components (Table 1). [4] Nearly all of these were for regions with significant Uyghur or other Muslim minority populations.

The scale of re-education facility construction can be reflected in local budget reports. For example, Akto County stated that in 2017 it spent RMB 383.4 million or 9.6 percent of its budget on security-related projects, including “transformation through education centers infrastructure construction and equipment purchase” (教育转化中心等基础设施建设和装备购置) (Akto Government, February 2). [5]

While there is no published data on re-education detainee numbers, information from various sources permit us to estimate internment figures at anywhere between several hundred thousand and just over one million. The latter figure is based on a leaked document from within the region’s public security agencies, and, when extrapolated to all of Xinjiang, could indicate a detention rate of up to 11.5 percent of the region’s adult Uyghur and Kazakh population (Newsweek Japan, March 13). The lower estimate seems a reasonably conservative figure based on correlating informant statements, Western media pieces and the comprehensive material presented in the long version of this article. It is therefore possible that Xinjiang’s present re-education system exceeds the size of the entire former Chinese re-education through labor system. [6]

Conclusions

China’s pacification drive in Xinjiang is, more than likely, the country’s most intense campaign of coercive social reengineering since the end of the Cultural Revolution. The state’s “war on terror” is arguably more and more a euphemism for forced ethnic assimilation.

Despite the strain on the local economy and the potentially disastrous long-term consequences for ethnic relations, Beijing’s support for Chen Quanguo’s extreme de-extremification measures is unlikely to wane. Under Xi Jinping, “foreign” religions such as Islam or Christianity have been kept on ever-tighter leashes and directed to “Sinicize” in accordance with “socialist core values” (New York Times, March 24, 2017). In that sense, Xinjiang’s re-education drive is effectively part of a larger, more subtle nationwide campaign.

Xinjiang’s status as the “core hub” of Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative has seemingly made Beijing hell-bent on pursuing a definitive solution to the Uyghur question. The frequently highlighted “successes” of Xinjiang’s re-education system may lead the state to adopt it elsewhere. Just as Xinjiang has become China’s testing ground for cutting-edge surveillance technology, the state may use the experiences gathered from large-scale re-education for its social reengineering efforts across the nation.

As pointed out by the scholar James Millward, we would do well to ponder whether what is happening in Xinjiang will stay in Xinjiang (New York Times, February 3).

Adrian Zenz is researcher and PhD supervisor at the European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal, Germany. His research focus is on China’s ethnic policy and public recruitment in Tibetan regions and Xinjiang. He is author of “Tibetanness under Threat” and co-edited “Mapping Amdo: Dynamics of Change”.

Notes

[1] See Mühlhahn, K., 2009. Criminal Justice in China: A History, pp.215-257. Deckwitz, S., 2012. Gulag vs. Laogai – The Function of Forced Labour Camps in the Soviet Union and China. MA Thesis, Utrecht University.

[2] Compare Tong, J., 2009. Revenge of the Forbidden City: the Suppression of the Falungong in China 1999-2005. Besides combating the Falun Gong, the state also employed “transformation through education” to re-educate Party members, targeting e.g. cadres with “non-conformist” (不合格) or “backward” (落后) mindsets (Li Derong, Baidu Scholar, 2002; Yuan Zhihua and Yi Waiping, Baidu Scholar, 2006). Finally, “transformation through education” is a common concept in the context of coercive isolated detoxification treatments (强制隔离戒毒) given to drug addicts.

[3] Often, neither advert texts nor specific job requirements indicate a relationship with vocational skills training. Kuqa County in Aksu Prefecture, where nearly the entire population is Uyghur, advertised 60 “education and training center” staff positions in the same intake as its convenience police station advert. The advert preferred recruitees with a background in the military or police. Qitai County in Changji Prefecture, with a Muslim population of 26 percent, advertised 200 assistant police positions specifically for its county “training center”. Several other adverts recruited “education and training center” staff in the same advert as other police positions, in nearly all instances without any degree requirement or relevant vocational training knowledge. Rather, Shayar (Shaya) County in Aksu mandated some of its future teachers to have degrees in law or Chinese language, both “skills” that are typically taught in political re-education facilities. Sources: see the long version of this article.

[4] Some bids referenced in Table 1 did not show cost estimates.

[5] Similarly, Charchan (Qiemo) County’s reported budget activities list RMB 105.1 million spending on security-related investments, including the construction of three re-education centers (教育转化中心) (Qiemo County, December 28, 2017). Likewise, Yakan (Shache) County’s 2017 budget report showed a RMB 1.5 million spending item on “legal system transformation through education” (司法教育转化), which likely pertains to operating expenses rather than facility construction. Similarly, Qaghiliq (Ruoqiang) County adjusted its 2017 budget to provide an additional RMB 6 million spending on re-education, likely also pertaining to running costs (Shache County, March 8, 2017; Ruoqiang County, January 29). All of these counties are located in regions with significant or majority Uyghur populations.

[6] Detailed sources and calculations for the statements made in this paragraph can be found in the longer version of this article.