by Punsara Amarasinghe 18 August 2021

Israel faced a series of existing challenges after its formation in 1948 followed by the first Arab-Israeli war, which made Israel triumphant against its hostile Arab nations. Nevertheless, the growing tension on the fragility of the newborn Jewish state provided an austere task for its first prime minister Ben Gurion. Given this geopolitical uncertainty that Israel was facing in its infancy stage, it would be rather tamping to assume Israel’s first prime minister David Ben Gurion was deeply interested in understanding Buddhism as a secular, rationalist value system. Moreover, the religious sphere of Israel was mainly driven by the ritualistic traditions of Orthodox Jewish Rabbis who showed no interest in an ascetic non-Abrahamic philosophy like Buddhism. Yet Ben Gurion’s intellectual curiosity with his secular Jewish standing against Orthodox Judaism widened his gaze to explore Asiatic religious philosophies. His journey to understand Buddhism was shaped by a series of letters correspondences with a Jewish German monk who lived in Sri Lanka and this profound relationship lasted till the Israeli premier retired from politics in 1964.

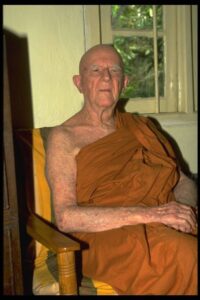

The scholar-monk Nyanaponika Thera was the person who helped the Israeli prime minister to increase his awareness and interest in Buddhism. Venerable Thero was born in Germany in 1901 to a Jewish family with the name Siegmund (Shlomo) Feniger. The awful circumstances that occurred after Hitler came into power forced young Feniger to leave Germany. After having spent few years in various Ashrams in India, Feniger arrived in Sri Lanka to study Buddhism under the tutelage of another German monk Nyanathiloka Mahathera. Feniger was ordained in 1936 and given the name Nyanaponika.

It was pure serendipity of events that led Ben Gurion to be acquainted with Ven. Nyanaponika. After the state formation in 1948, Tel Aviv was well aware of the futility of making diplomatic ties with its hostile neighbours. Thus, Israel adopted its famous doctrine “Strategy of the periphery”, which sought to cement relations with far-east Asian nations. It was in this context Burmese premier U Nu made a state visit to Israel in 1955 as the first foreign head of state to visit Israel. It was by no means a just diplomatic victory for Israel as U Nu’s visit resulted in forming a close friendship between two prime ministers that would last for the rest of their lives. U Nu was the first person, who cultivated Ben Gurion’s interest in Buddhism by gifting him some books on Buddhist teachings. It was further accelerated when Gurion requested U Nu to introduce him to Asian Buddhist scholars. Meanwhile, the Israeli ambassador in Tokyo requested Sir Susnatha de Fonseka, who happened to be Sri Lanka’s ambassador in Japan to assist in finding an erudite Buddhist scholar from Sri Lanka. Indeed, Sir de Fonseka took a keen interest in this matter as he wrote a cable to Sri Lankan government officials in Colombo to approach Ven. Nyanaponika Thera. Followed by the Sri Lankan government’s official request Nyanaponika Thera wrote his first letter to Ben-Gurion in June 1956, which marked the seven years of correspondence between the monk and the prime minister.

In the very first letter, Nyanaponika introduced himself as a simple German Jew living in Sri Lanka as a Buddhist monk. But, this introduction was a modest gesture of the monk as at the time of writing his fame and erudition were well received in the Theravada Buddhist world as one the leading authorities in “Dhamma”. In the opening letter, Nyanaponika Thera alludes to the political turmoil faced by Israel in the aftermath of the Sinai campaign in 1956. Showing his Jewish sentiments beyond the yellow robe, he states

“I was deeply moved that even in these grave days for Israel and with your great burden of responsibility of being prime minister. your interest in the Buddha’s teachings has not slackened”.

At the time of the first correspondence, Ben-Gurion was 70 years old and Nyanaponika was 55-year-old. Despite the age gap between the two, both men had witnessed severe transformations in their ideological convictions. For instance, despite being the first prime mister of the Jewish state, Ben Gurion was not convinced by the Orthodox Jewish culture based on Rabbaic rituals. He was more agnostic and inclined to rely on rationality. This feature of Ben-Gurion’s character aptly reflects in his letters to Nyanaponika Thera from the way Gurion questioned the Buddhist philosophy. When Ven. Nyanaponika highlighted suffering “ dukkha” as the first noble truth, that claim was questioned by Ben Gurion from a different perspective. In his answer, Gurion writes “What I cannot accept, though, is the first noble truth of the Buddha, that life us suffering. There is certainly suffering in life, but to me, life is joy and creative effort as well”. Ven. Nyanaponika was aware of the unfamiliarity of Ben Gurion on Eastern philosophical views or the metaphysics of Eastern religions, thus the answer written by him contained rather rudimentary analysis on the Buddhist concept of suffering followed by a list of literature to increase the prime minister’s curiosity.

Nyanaponika Thera never forgot his Jewish background regardless of his personal transformation into a Buddhist monk. It was conspicuous from his often references to the Jewish nation in his letters to the Israeli prime minister and Thera had attempted many times to use Buddhism as a healing method for the agonies and deprivations faced by the Jews throughout their turbulent times in history. In his letters Thera writes “Among our Jewish people that has undergone and still undergoes so much suffering and yet preserved its inner strength, there might be some to whom the Buddha’s teaching of deliverance from suffering will appeal”

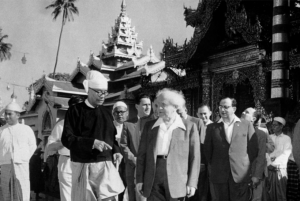

The letter correspondences between Ben-Gurion and Nyanaponika epitomize a benign attempt to build a dialogue between two religious traditions in a liminal period of modern history. Perhaps, it contains every intrinsic value to compare with the famous “Milinda Panha” in Buddhist literature. However, unlike King Milinda, who asked questions from Nagasena Thera, Ben-Gurion did not become a Buddhist at the end of the letter correspondences with Nyanaponika. Instead, he remained his unshaken skepticism while showing eagerness to learn Buddhism. Both of them met in Rangoon in 1961, when Ben Gurion visited Burma as a gust of Burmese Premier U Nu. The time that Ben-Gurion spent in Rangoon brought him an ideal opportunity to discuss with Nyanaponika Thera about the basic Buddhist doctrine and also, he learned Vipassana meditation, which appeared to be bizarre news for Israeli media, who lampooned the Israeli prime minister’s monastic experience as an act eccentricity. Due to the inimical reaction that arose from the Orthodox Jewish clergy in Israel, Ben Gurion was hesitant to make an official invitation to Ven. Nyanaponika to visit Israel. But, he privately invited the monk to visit the Jewish state, which never became true as a result of many bureaucratic errors.

Ben-Gurion’s zealousness in learning Buddhism was not short-lived amid all the political pressure around him. Even though he was not fully convinced by Buddhist concepts such as Rebirth and Karma, Gurion’s interest in learning Buddhist philosophy was not slaked as the correspondence between the two continued for another six years. It is plausible to argue that Nyanaponika Thera could initiate a genuine interest in Ben Gurion, which brought considerable changes to the Israeli premier’s character. In 1957 when the Israeli legislature ( Knesset) was attacked by an Iraqi Jewish immigrant, among the government members injured, Ben Gurion was said to have remained the calmest person.

Ben Gurion passed away in 1973 after retiring from politics and Nyanaponika Thera continued his spiritual journey in Sri Lanka for another two more decades till he passed away in the ripping age at 94. Today many Israeli universities have departments on Buddhist studies and South Asian philosophies as interest among Jewish scholars on Buddhist meditation continues to grow.

( Ben-Gurion in Burma )