by Anoushka Roy 29 February 2020

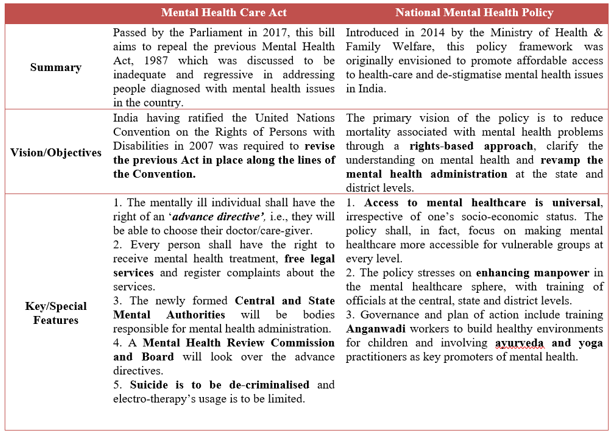

Despite there being inherent resistance to addressing mental health issues in the Indian society, there exists a policy framework for the same in the form of legislation. This fact, however, is known to few, which is where the fundamental problem of mental health as a ‘taboo’ persists in the country. The apparent lack in efforts to create awareness regarding issues under mental health, which is a huge umbrella subject under health, has cumulatively contributed to this hesitation in institutionalising a comprehensive mental health policy for the country. In this context, it is fundamental for us policymakers to understand the scheme in place and how it translates as a policy on ground. The objective of this policy brief would be to give a broad overview of the two most important government mechanisms in place for addressing mental health in the country- the Mental Health Care Act, 2017[i] and the National Mental Health Policy of India, 2014[ii].

What is wrong, then?

Despite the existence of a legal and a policy framework, India’s mental health statistics paint a scary picture. The reasons to be attributed to this are simple for anyone to understand. De-stigmatising mental health is an expensive affair, and an administration which has largely ignored this part of the process is subjecting mental health issues to gross simplification. This section discusses where the legislative and policy framework have gone wrong.

a. Presumptions and Assumptions: The mental health policy framework considers a person having the capacity to make decisions for them if they are able to understand, retain, use information and communicate their decision. However, this places the burden of proving capacity on someone who is already under mental stress. Therefore, it positions a mentally ill patient at a severe disadvantage. Secondly, by decriminalising suicide, the policies assume that every person who attempts suicide is subject to mental health treatment, which might not be the cause for attempting suicide in the first place. Gendered mental health also remains absent from the narrative of the documents.

b. Funding?: While funding remains unaddressed in either of the frameworks, it is important to note that public health is a state subject and requires the state to administer the same. However, neither of the frameworks addresses the allocation of funds to the state. The Central government, thus, shifts the burden of financial administration.

c. Advance Directives are exploitative: It might initially seem that this component helps the patient, but the clause attached to it tells otherwise. If the care-giver refuses to follow the directive, they may or may not apply to the Review Board for modification, making it an optional move and thereby, subjecting the patient to exploitation.

d. Question of Assets: The policies fail to address what happens to the question of assets owned by a mentally ill patient if they are unable to make decisions for the same.

e. Absence of compulsory insurance: Most importantly, none of the frameworks address or quantify on how a mentally ill person may or may not get access to affordable insurance coverage, considering that mental health treatment is very expensive.

In other areas, the policies fail to answer questions about how the professionals would be trained. How much budget would be allocated to the same? What happens to mental healthcare outside hospitals? What happens to healthcare at the community level? Several reports have also questioned the quality of government-run mental health practice centres. Research clearly shows the complete lack of resources on ground during the implementation of the policies. Affordability, therefore, still remains an unanswered question. In conclusion, what is to be understood is the fact that the existing policy framework at the central level is agnostic to the district-level implementation and cuts a shoddy figure in terms of practical feasibility, but does get full marks on a blanket, decorative, black and white document.

Why the need to focus on mental health in India?

Mental health is a complex issue, one that still requires committed investment even in the West. While placing this subject in the Indian context, the issue becomes far more complicated for policymakers because of the stigma attached with mental health in the Indian society. Invisible illness has been time and again discarded by the Indian commons. A simple analysis of the available resources in India would tell us why our country needs to re-think treatment of mental illness. This section will highlight the various narratives as to why mental health is a dire area of research- the resources narrative, the youth narrative and the feminist narrative.

A resource analysis in terms of the availability of doctors versus the demand for psychological/psychiatric attention is glaring and puts any policymaker in a difficult position. In a brilliant academic report compiled by the Department of Economics, UC Santa Cruz, the authors highlight the need-availability gap of out-of-hospital mental illness nurses and doctors in India. They recreate the following table from an erstwhile report[iii]:

It becomes evident that this sheer shortage in resources is seconded by similar figures at the district communities and rural primary healthcare centres, making it an imperative for policymakers in the government to restructure the mental health administration and decentralise it. The World Health Organisation (WHO) also estimates that the economic loss in India due to mental health would be around $1.3 trillion between 2012 and 2030.

The youth narrative is one that we have heard several times. In the 2015 Mental Health Survey of India, the NIMHANS, Bengaluru has reported that 9.8 million teenagers in the age group 13-17 suffer from depression[iv], requiring immediate attention. This stems from the immense pressure that the Indian education system confers on the youth, which is also a separate policy issue.

The feminist narrative, a fairly subdued one, highlights the greater vulnerabilities of women to mental illness as compared to men. Several women suffer from post-natal depression, post-traumatic disorder, economic inequality which heavily contributes to the failing mental health of our women. The WHO reports that 20% of the Indian mothers are hit by depressions because of the patriarchal build of an Indian home. Gender-based violence, lack of decision-making power and lack of economic opportunities are the leading factors for mental trauma amongst India’s women.

WHO reports that 7.5%[v] of India’s populations suffer from some form of mental illness, whereas the treatment gap is over 70%, making it an issue which needs immediate attention and a comprehensive approach.

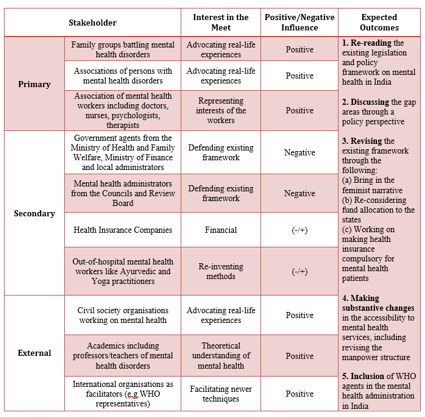

Towards Practical Feasibility: Roundtable for Re-imagining Mental Health Administration in India 2020

This would be the title of the proposed stakeholder’s roundtable on the issues elaborate above. The title makes evident that the reason why the stakeholder meet was taking place is because of a lag in the implementation process of the existing mental health administration in India. The objective of the meet would be to come up with feasible programmes for revamping the existing structure and giving a head-start to the mental health programme.

Ayushmaan Bharat: Election Gimmick or Actual Policy?

Since its launch in 2018, there has been a lot said and written about the flagship health scheme of the present ruling government, Ayushmaan Bharat. There is common understanding among several people that this scheme has been poorly thought through, with only glitter which disguises to be the first step toward ‘universal healthcare’ in India. In retrospect, however, a simple analysis of the scheme tells us otherwise. With several states like West Bengal refusing to implement the scheme and high-performing states like Chhattisgarh refusing to continue with the scheme tells us that there is something incredibly wrong with the way this government has approached healthcare policy in the country. This opinion piece focuses on the faults in the scheme and highlights its impact on the country’s health indicators and budget.

At the outset, the scheme has two parts: an insurance cover of 5 lakh rupees per family to 10 crore families and aspires to set up 150,000 health and wellness centres. The latter is only a revision of the erstwhile Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and the former poses that this government has failed in its basic mathematics. If we were to calculate the gross expenditure that this government will incur for the scheme annually, it would come to around Rs 50,000 crore, that is, if a family spends even one lakh out of their allocated 5 lakh rupees. Now, the budget allocated for the scheme is Rs 3,200 crore in 2020, which makes a deficit of Rs 46,800 crore. Essentially, the government did not highlight this deficit while making the budget estimates for the scheme as a result of which the mathematics is unprecedented. This is only as far as annual total expenditure is concerned. Even if the budget allocated is raised to Rs 10,000 crore for 10 crore families, it comes to Rs 1,000 per family or Rs 200 per person on an average per year. That is fundamentally detrimental to a person’s basic right to access healthcare. The scheme says it aspires to be the largest insurance scheme but hides the fact that the coverage of persons is being increased by decreasing per capita expenditure on healthcare.

Another critique of this scheme is that it takes away attention from primary healthcare to only focus on tertiary and secondary healthcare, which is needed, but isn’t the government’s first concern. By shifting focus from primary health services and by allocating Rs 5 lakh per family for a year, it is an undeniable inference that fraudulent activities are bound to step in. Even if we assume that a family does not require half of 5 lakh rupees per year, several reports have shown how forged relationships and beneficiaries are enrolling under each family to make use of the allocated money. This means that the money is being diverted to middlemen and private sector healthcare through a gross loot of public money.

This inherent contradiction between dearth of money at an overall level and abundance of money at a unit level tells us that the government’s policymaking has not been well thought through. In no way can it improve our health indicators because of the growing disadvantage of the vulnerable groups, who still cannot access this scheme given the poor healthcare facilities in rural areas. Additionally, this confuses a budget analyst severely because health being a state subject, poses serious challenges to the budget allocation within the state and the use of funds at the state level. In essence, therefore, the healthcare scheme cuts a sorry figure for policymakers in the government body and refutes the fundamentals of universal healthcare.

Anoushka Roy is currently a post-graduate student of Public Policy at the

National Law School of India University, an erstwhile student of International

Relations at Jadavpur University. Her interest areas include rural development,

migration and global decision-making.

[i] For the full legislation, please read https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Final%20Draft%20Rules%20MHC%20Act%2C%202017%20%281%29.pdf

[ii] For the full policy document, please read https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/National_Health_Mental_Policy.pdf

[iii] To read the full report, visit https://economics.ucsc.edu/research/downloads/mirza_singh_mental_health_04sep1.pdf, page 8. The need factor is calculate with an assumption of 1 doctor for every 100,000 persons, 1.5 psychologists for every 100,00 persons, two social workers per every 100,00 persons and one nurse per 100,00 persons.

[iv] https://yourstory.com/herstory/2019/10/world-mental-health-day-women-suicides