Abdul-Jalilu Ateku, University of Nottingham

All the world’s a stage; And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts. (As you like it, Act II, scene VII, William Shakespeare.)

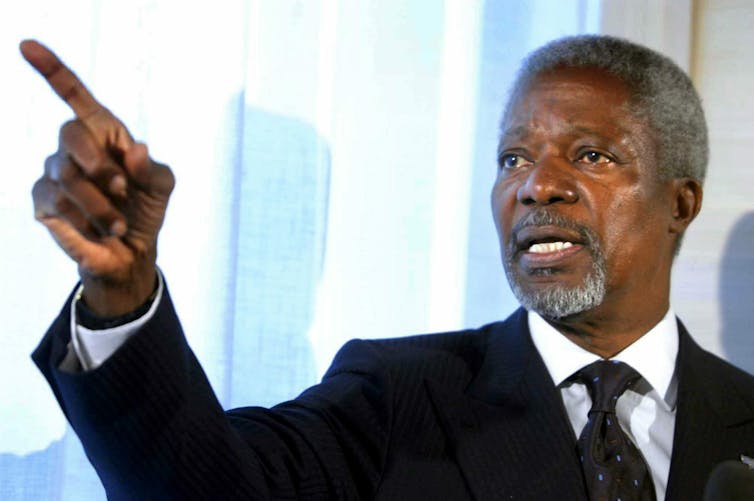

Indeed, Kofi Annan, born in 1938, entered the world in the City of Kumasi in Ghana, and exited the world in 2018 as a humanitarian, a true statesman and a peacebuilder.

He became Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN) a few years after the demise of the Soviet Union. The collapse of the bi-polar world reduced to the barest minimum the constraints imposed by the Cold War rivalry on the world body. It also led to the expansion of its role and responsibilities to address the new challenges and dimensions of security.

Annan’s tenure began a few years after the (re)introduction of two important international security lexicons – peacebuilding and human security. These two were popularised in the UN commissioned works by former Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s An Agenda for Peace (1992) and the Pakistani economist, Mahbub ul Haq. Boutros-Ghali’s initiative expanded the UN’s role and responsibilities to the world. It also redefined global peace and security architecture.

The 1990s was characterised by complex and intractable armed conflicts. The period saw a significant shift from inter-state to intra-state conflicts. There was a rise in the number of

failed states as well as egregious violations of human rights.

As the Under-Secretary-General of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, and later the Secretary-General, Annan’s task of overseeing the implementation of the new security agenda was no doubt arduous.

The fight against poverty

Throughout his life Annan committed himself to peace and security, human rights and rule of law. He was committed to ensuring respect for human rights and improving human security. Both were considered important in improving the quality of living of people. On one occasion he remarked:

…anyone who speaks forcefully for human rights but does nothing about human security and human development – or vice versa – undermines both his credibility and his cause. So let us speak with one voice on all three issues.

He pursued the agenda of improving the quality of people by getting world leaders to commit themselves to addressing the basic concerns of the world’s population – poverty. In his 2000 report, We the peoples: the role of the United Nations in the 21st century, he urged member states to:

Put people at the centre of everything we do …. to make their lives better.

In the concluding part of the report, Annan admonished:

Free our fellow men and women from the abject and dehumanising poverty in which more than 1 billion of them are currently confined.

Throughout his international public service, measures to address the basic needs of people were ever present, both in his words and deeds. Even on retirement, he continued to work for the improvement of the living standards of ordinary people.

The reformist

Annan was a reformist. On taking up the post as the seventh Secretary-General of the UN, he drove the implementation of two management reports on reform. The first introduced a cabinet kind of body which assisted the Secretary-General in the effective running of the organisation.

EPA-EFE/Lynn Bo bo

The second established of the position of Deputy Secretary-General and the reduction of administrative costs to the world body. He presided over reforms intended to make the UN an effective international peace and security interlocutor. In his progress report he made further far reaching recommendations for the expansion of the Security Council and a number of other reforms that brought about significant changes to the UN.

His past experiences shaped his international engagements, especially on international intervention to save humanitarian catastrophes. The failure of the UN to stop the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 and the Srebrenica massacre when Annan served as the head of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations were key events in this context.

Under Annan, the UN General Assembly in 2005 endorsed the doctrine of “Responsibility to Protect” following the incorporation of this doctrine in his report, Larger Freedom.

In the preparation to invade Iraq in 2003, Annan condemned the US and the UK, urging them not to do so without the support of the UN. He believed the intervention didn’t conform with the UN charter, and was therefore illegal.

Reflections

In his memoir which he coauthored with his former advisor and speechwriter, Nader Mousavizadeh, Annan, he reflected on his roles at the UN.

On the Rwandan genocide, one of the significant lapses that dented the UN’s peacekeeping reputation, Annan reported on how he lobbied about 100 governments – and made personal calls to others – to assist with the passage of the Security Council Resolution (918) to dispatch about 5,500 troops to the country. He recalls how he received no single serious offer for troop contribution.

The 1999 independent investigation into what had happened categorically concluded that the UN had failed to prevent, and stop, the genocide in Rwanda. As Secretary-General during the investigation, Annan accepted responsibility of the lapses during the genocide in Rwanda. He said:

All of us must bitterly regret that we did not do more to prevent it,

pointing out that UN peace force at the time was “neither mandated nor equipped” for the kind of forceful action needed to prevent the genocide.

Nonetheless with a deeper refection, Annan said:

On behalf of the United Nations, I acknowledge this failure and express my deep remorse.

Recounting more recently on the genocide in Rwanda and his later diplomatic undertakings after the end of his tenure as the Secretary General, Annan said he’d learnt some useful lessons:

I realised after the genocide that there was more that I could and should have done to sound the alarm and rally support. This painful memory, along with that of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has influenced much of my thinking, and many of my actions, as secretary-general”.

He was to put these lessons into practice as he continued to pursue avenues for peace in conflicts around the world. For example, six months after his appointment as the UN-Arab League Special Envoy to Syria, Annan resigned. His reasons included the stalemate in the Security Council to take measures that could ensure a peaceful resolution to the Syrian crisis as well as the intransigence of both the Assad regime and the rebels towards a peaceful outcome.

And in 2016 he headed the Rakhine Commission which was appointed to look into the Rohingya conflict in Myanmar. The commission’s recommendations were unpopular to both sides. But in 2018 the Myanmar civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi accepted the commission’s recommendations and convened a new board, ostensibly to implement them.

![]()

Annan acquitted himself well as an international diplomat, a humanist and peace-builder. He lived a fulfilled life, and contributed significantly in his chosen career. Kofi ‘Damirifa Duei Duei ne amane hunu’ (Rest in Peace).

Abdul-Jalilu Ateku, PhD Candidate in International Relations, University of Nottingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.