BBC News 20 August 2019

Nuclear-armed neighbours India and Pakistan have fought two wars and a limited conflict over Kashmir. But why do they dispute the territory – and how did it start?

How old is this fight?

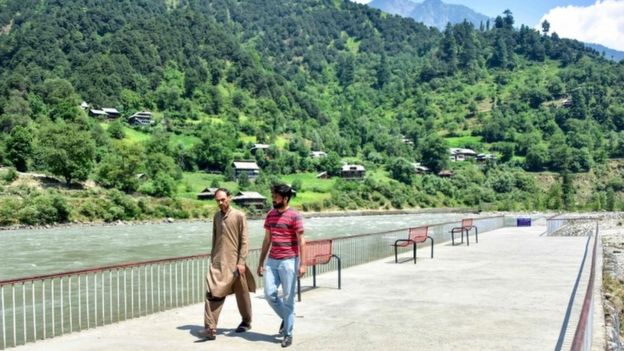

Kashmir is an ethnically diverse Himalayan region, covering around 86,000 sq miles (138 sq km), and famed for the beauty of its lakes, meadows and snow-capped mountains.

Even before India and Pakistan won their independence from Britain in August 1947, the area was hotly contested.

Under the partition plan provided by the Indian Independence Act, Kashmir was free to accede to either India or Pakistan.

The maharaja (local ruler), Hari Singh, initially wanted Kashmir to become independent – but in October 1947 chose to join India, in return for its help against an invasion of tribesmen from Pakistan.

A war erupted and India approached the United Nations asking it to intervene. The United Nations recommended holding a plebiscite to settle the question of whether the state would join India or Pakistan. However the two countries could not agree to a deal to demilitarise the region before the referendum could be held.

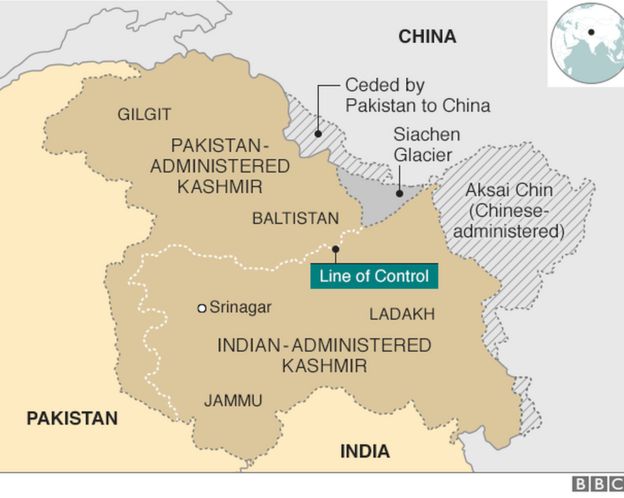

In July 1949, India and Pakistan signed an agreement to establish a ceasefire line as recommended by the UN and the region became divided.

A second war followed in 1965. Then in 1999, India fought a brief but bitter conflict with Pakistani-backed forces.

By that time, India and Pakistan had both declared themselves to be nuclear powers.

Today, Delhi and Islamabad both claim Kashmir in full, but control only parts of it – territories recognised internationally as “Indian-administered Kashmir” and “Pakistan-administered Kashmir”.

Why is there so much unrest in the Indian-administered part?

An armed revolt has been waged against Indian rule in the region for three decades, claiming tens of thousands of lives.

India blames Pakistan for stirring the unrest by backing separatist militants in Kashmir – a charge its neighbour denies.

Now a sudden change to Kashmir’s status on the Indian side has created further apprehension.

Indian-administered Kashmir has held a special position within the country historically, thanks to Article 370 – a clause in the constitution which gave it significant autonomy, including its own constitution, a separate flag, and independence over all matters except foreign affairs, defence and communications.

On 5 August, India revoked that seven-decade-long privileged status – as the governing party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had promised in its 2019 election manifesto. The Hindu nationalist BJP has long opposed Article 370 and had repeatedly called for its abolishment.

Telephone networks and the internet were cut off in the region in the days before the presidential order was announced. Public gatherings were banned, and tens of thousands of troops were sent in. Tourists were told to leave Kashmir under warnings of a terror threat.

Two former chief ministers of Jammu and Kashmir – the Indian state which encompasses the disputed territory – were placed under house arrest.

One of them, Mehbooba Mufti, said the move would “make India an occupational force in Jammu and Kashmir,” and that “today marks the darkest day in Indian democracy”.

Pakistan fiercely condemned the development, branding it “illegal” and vowing to “exercise all possible options” against it.

It downgraded diplomatic ties with India and suspended all trade. India responded by saying they “regretted” Pakistan’s statement and reiterating that Article 370 was an internal matter as it did not interfere with the boundaries of the territory.

Within Kashmir, opinions about the territory’s rightful allegiance are diverse and strongly held. Many do not want it to be governed by India, preferring either independence or union with Pakistan instead.

Religion is one factor: Jammu and Kashmir is more than 60% Muslim, making it the only state within India where Muslims are in the majority.

Critics of the BJP fear this move is designed to change the state’s demographic make-up of – by giving people from the rest of the country to right to acquire property and settle there permanently.

Ms Mufti told the BBC: “They just want to occupy our land and want to make this Muslim-majority state like any other state and reduce us to a minority and disempower us totally.”

Feelings of disenfranchisement have been aggravated in Indian-administered Kashmir by high unemployment, and complaints of human rights abuses by security forces battling street protesters and fighting insurgents.

Anti-India sentiment in the state has ebbed and flowed since 1989, but the region witnessed a fresh wave of violence after the death of 22-year-old militant leader Burhan Wani in July 2016. He died in a battle with security forces, sparking massive protests across the valley.

Wani – whose social media videos were popular among young people – is largely credited with reviving and legitimising the image of militancy in the region.

- The teenager blinded by pellets in Kashmir

- ‘Modi’s Kashmir move will fuel resentment’

- WATCH: The boy drawing Kashmir’s conflict

Thousands attended Wani’s funeral, which was held in his hometown of Tral, about 40km (25 miles) south of the city of Srinagar. Following the funeral, people clashed with troops and it set off a deadly cycle of violence that lasted for days.

More than 30 civilians died, and others were injured in the clashes. Since then, violence has been on the rise in the state.

More than 500 people were killed in 2018 – including civilians, security forces and militants – the highest toll in a decade.

Weren’t there high hopes for peace in the new century?

India and Pakistan did indeed agree a ceasefire in 2003 after years of bloodshed along the de facto border (also known as the Line of Control).

Pakistan later promised to stop funding insurgents in the territory, while India offered them an amnesty if they renounced militancy.

In 2014, India’s current Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power promising a tough line on Pakistan, but also showed interest in holding peace talks.

Nawaz Sharif, then prime minister of Pakistan, attended Mr Modi’s swearing-in ceremony in Delhi.

But a year later, India blamed Pakistan-based groups for an attack on its airbase in Pathankot in the northern state of Punjab. Mr Modi also cancelled a scheduled visit to the Pakistani capital, Islamabad, for a regional summit in 2017. Since then, there hasn’t been any progress in talks between the neighbours.

Are we back to square one?

The bloody summer of street protests in Indian-administered Kashmir in 2016 had already dimmed hopes for a lasting peace in the region.

Then, in June 2018, the state government there was upended when Mr Modi’s BJP pulled out of a coalition government run by Ms Mufti’s People’s Democratic Party.

Jammu and Kashmir was since under direct rule from Delhi, which fuelled further anger.

The deaths of more than 40 Indian soldiers in a suicide attack on 14 February, 2019 have ended any hope of a thaw in the immediate future. India blamed Pakistan-based militant groups for the violence – the deadliest targeting Indian soldiers in Kashmir since the insurgency began three decades ago.

Following the bombing, India said it would take “all possible diplomatic steps” to isolate Pakistan from the international community.

On 26 February, it launched air strikes in Pakistani territory which it said targeted militant bases.

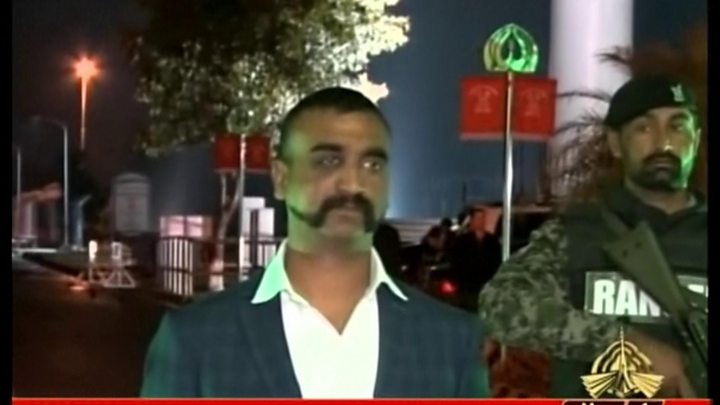

Pakistan denied the raids had caused major damage or casualties but promised to respond, fuelling fears of confrontation. A day later it said it had shot down two Indian Air Force jets in its airspace, and captured a fighter pilot – who was later returned unharmed to India.

Kashmir remains one of the most militarised zones in the world.

So what happens next?

India’s parliament has now passed a bill splitting Indian-administered Kashmir into two territories governed directly by Delhi: Jammu and Kashmir, and remote, mountainous Ladakh.

China, which shares a disputed border with India in Ladakh, has objected to the reorganisation and accused Delhi of undermining its territorial sovereignty.

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan has vowed to challenge India’s actions at the UN security council, and take the matter to the International Criminal Court.

In an ominous warning, he said: “If the world does not act today… (if) the developed world does not uphold its own laws, then things will go to a place that we will not be responsible for.”

But Delhi insists that there is no “external implication” to its decision to reorganise the state as it has not changed the Line of Control or boundaries of the region.

US President Donald Trump has offered to mediate in the crisis – an overture that Delhi has rejected.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published