Violence against women is not a new phenomenon in the transitional societies of South Asia. Since the ancient period to today’s post-modern era the prevalence and forms of violence against women are muddling through clouds to darken the dawn of gender equality within the sphere of family, education, profession, culture, politics, economy, religion, and society in South Asia. Even we can debate on the progress of the women’s condition considering the changing dimensions of time, context and society though the wildest forms of violence against women -i.e. rape, incest, honor killing, dowry, acid throwing etc.- are not changed and reduced over time. Nowadays the South Asian nations are suffering from a high rate of rape and subsequent murder, questioning the structural and psychological changes resulted by modernity in our patriarchic societies.

Bangladesh is one of the most victimized nations where the culture of rape is still sketching all pain for the women. Tanu’s rape and murder is the latest scare of violence that is being perpetrated against women in Bangladesh. As social movements and social media gather steam around the issue, ‘Justice for Tanu’ has shaken the conscience of the people of Bangladesh. The social movements demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’ are revealing a rising face of micro-democracy within the liberal democratic order where individuals, communities, social organizations, and social media are protesting by narrowing their focus on a fair trial for Tanu’s rape and murder case but broadening their demands, conscience and publicity to ensure equality, rights, physical and psychological security for every woman in Bangladesh, in the South Asian neighborhood.

The Broader Picture of Rape in Bangladesh

Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, on the basis of the information collected from 14 national dailies, reported that since 2008 to 2015 a number of 4304 women were raped among them 740 were killed after rape. The Parishad also reported 243 incidents of rape where 12 women died by rape and 3 committed suicide after their rapes, from January-April 2016.

Table: Incidents of Rape and its subsequent Deaths from 2008-2016 (till April)

| Year | Incidents of Rape | Death by Rape |

| 2008 | 307 | 114 |

| 2009 | 393 | 130 |

| 2010 | 593 | 66 |

| 2011 | 635 | 96 |

| 2012 | 508 | 106 |

| 2013 | 516 | 64 |

| 2014 | 544 | 78 |

| 2015 | 808 | 85 |

| 2016 (Jan-April) | 243 | 12 |

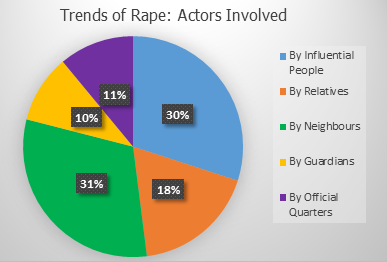

In 2008, Mahila Parishad had also sketched the trends of rape violence against women where 31 percent of these rape victims were between 11-15 years of age. However, the trends of rape and the actors involved can from several quarters.

From 1997-2010, the Legal Aid Department of Bangladesh Mahila Parishad reported 7,232 cases of rape, of which 1,372 women died and 2,854 were gang raped. In 2014 and 2015, almost 9,000 cases of violence have been registered with the police. Dhaka Medical College affiliated the ‘One Stop Crisis Centre’ reports that everyday four to five women are reported to be raped, while the 14 units of Women and Child Repression division of the police has recorded 22,291 cases of abuse in 2014 and 21,220 cases in 2015.

The Narrow Picture: Tanu Rape and Murder

Sohagi Jahan Tanu, a 19 years old, second year history student of Comilla Victoria College and also a member of Victoria College Theatre, went missing on March 20, hours after she had gone out of her house at Comilla Mainamati Cantonment for private tuition. Later, Tanu’s father, Yaar Hossain found his daughter lying senseless with severe injuries to her body in a bush adjacent to their house. She was then whisked off to Combined Military Hospital where doctors declared her dead. After her death a growing intensity of social movements and actions across the country were observing where the destiny of the demand ‘Justice for Tanu’ dangled with the outcomes of the rising micro-democracy in Bangladesh.

Politics of Autopsy and DNA Test

The causes of the murder and murderers are still not revealed or identified. The police could not make any headway in the investigation and none were arrested. Even the CID questioned several army personnel for their involvement in this case, but the investigation report is yet to be out. The first autopsy was completed on Tanu’s body on 21 March. But no evidence of rape as well as the causes of death were found in the first autopsy report. Failure of the first autopsy report to provide any pathway for further productive investigation revealed a new face of social movements demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’. Considering these upheavals a Comilla court had ordered exhumation of Tanu’s body from the grave for a fresh autopsy on 28 March. Following the order on 30 March the second autopsy of her body was done by the newly formed medical board of Comilla Medical College.

On 17 May, the CID reported that they found sign of rape in the DNA samples of Tanu’s teeth and cloths. However, since the second autopsy on Tanu’s body, politics centering autopsy and DNA test had started between the Forensic department of Comilla Medical College and the Forensic department of CID. The Forensic department of Comilla Medical College demanded the report of DNA test from the Forensic department of CID but the latter refused to provide the DNA report to the former the desired document without court order. None of these departments submitted or published their reports of second autopsy in order to maintain their legal confidentiality. Also the growing intensity of social movements had been preventing them from endorsing their reports, whereby the social groups were suspecting the dilemma of controversy of their findings. It has been perceived that the report of the second autopsy would differ vehemently from the findings of the first autopsy.

Dimensions of the Social Movements centering ‘Justice for Tanu’

Since the rape and the subsequent murder of Tanu, micro-democratic waves of social movements revealed the following dimensions:

Broad ideas but narrow focus: Violence against women, more specifically rape, is not a new phenomenon in Bangladesh. Everyday almost four or five women are harassed sexually but most of the cases do not get publicity. Since the rape of Yasmin Akhter by three policemen in 1995 there has been a growing upheaval against rape in Bangladesh. The ongoing social movements centering ‘Justice for Tanu’ are representing the screams, grievances and demands related to every rape incident that had been perpetrated against women in Bangladesh.

Actors Engaged: The main thrust of these social movements centering Tanu murder, links social movement actors to widen the civic engagement as well as civic culture from individuals to communities, from communities to socio-cultural organizations, from socio-cultural organizations to the greater society in order to institutionalize the micro dimensions of social change. The actors engaged in these new social movements include students from all levels, mass people, a Social Action Committee (a platform of 68 women, Human Rights and development organizations), the members of the Gonojagoron Mancha (mass-upsurge stage), socio-cultural organizations, radical political parties, human rights organizations particularly working on women issues (Bangladesh Mahila Parishad). More specifically the Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) is playing a leading role in the legal arena as well as in the public sphere to draw attention for the Tanu murder case to be solved which would have greater implications to address and solve the previous rape cases.

Forms of action: The major trend of these movements is to articulate demands without using any violent means. The forces of these movements are driven by non-partisan societal goals rather than to seek any political interest. However, the actors engaged in expose and raise their demand of ‘Justice for Tanu’ in a peaceful manner following a series of public and social actions which include human chain, procession, strike, blockade, assemblage, long march, showing placard, candle lighting, press briefing, organizing cultural programs, writing opinion and blog and staging drama etc. The students declared the premise of the Shahid Minar (Martyr Monument) of the Comilla Victoria College as ‘Tanu Mancha (stage)’

Role of social media: The social media played a decisive role in shaping the ins and outs of the movements. Particularly, facebook provided a strong basis for the rise and growth of the movements demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’ where the engaged actors use this domain constructing events, pages, groups, and posting etc. Basically the youths organized as well as assembled for long march, protest, procession and so on using this cyber-domain. They also shot many photographs of micro-protest and shared these in facebook and twitter which had shaken the conscience of the mass in demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’.

Micro-democracy of the protest: The macro portion of the history of Bangladesh is full of bloody wars, military coups-counter coups, harsh movements for establishing Caretaker Government (CTG), destructive Hartals (strikes) to establish political supremacy. But the movements demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’ are not seeking any legitimate or illegitimate power or abolishing any authority from power rather to protest peacefully against violence on women narrowing their focus on Tanu murder but broadening their vision of ensuring a culture of non-violence, rule of law, gender equality and security eradicating a culture of impunity, legal loopholes, governance failure and weak state capabilities for elite domination, and socio-cultural prejudices and stigmas from individual to social domain.

The rise of micro-democracy in Bangladesh: A case of ‘Justice for Tanu’

Since Tanu rape and murder, the nation is feeling a series of micro-knocking at the door of the existing liberal democratic order where the rise of micro-democracy is taking place. Demands of ‘Justice for Tanu’ from the bottom, are emphasizing the actions of individuals, communities, socio-cultural organizations, and social media to hold the State accountable. As these movements were slowly fading, a 13 year old girl from Rajshahi demonstrated her anger as she roamed around the streets of this divisional city with a placard that reads: ‘No one killed Tanu’.

First, the girl is questioning the willingness of the law enforcement and investigating agencies as well as the legal structure in dealing with a case that could possibly put the military in the dock. Secondly, she is also bringing to light how easy it is for things to fade away from public memory. When Tanu was murdered it became leading news, but now it stands consigned to inconspicuous corners. Third, the Rajshahi girl is talking about the pending cases of violence against women. Fourth, the teenage girl is not only talking about the visible physical violence against women but she is also highlighting the growing intensity and prevalence of psychological, familial, inter-personal, official, organizational, and sexual harassments against women – a neo-social diseases contaminating the social as well as inter-personal fabric. Fifth, she is also talking about the patriarchal character of the society of Bangladesh as well as the whole South Asia where a culture of violence against women continues to prevail. Sixth, her statement, ‘No one killed Tanu,’ questions the efficacy of institutional arrangements of the state to provide security for women against sexual and other kinds of gender related violence.

The anger of the 13 year old Rajshahi girl is valid and bears a message for the State, as well as the society to take effective steps in order to diminish and eliminate violence against women. The only matter of satisfaction in all of this is that Bangladesh is witnessing new social movements, where the social groups and organizations are assembling to stir social and cultural changes. Now people are organizing not for capturing the State’s power and meeting their political interests. Rather, they are gathering to ensure peace and stability, environmental security, justice for the greater humanity.

These movements are often termed as ‘new populism’ or ‘disorderly politics’ or ‘new politics’ or ‘non-institutional politics’ or ‘reformist politics’ based on collective action, network society, informal networks, participatory decision-making and decentralized structure. The movements led by social organizations and in the social media circles demanding ‘Justice for Tanu’ bear a message: government accountability is a must. This new politics is expected to bring a new dawn of micro-democracy that would reflect public opinion in the State’s activities. And, it will be the outcome of this micro-democracy that would come to ensure that a gender-balanced and equal Bangladesh is no longer a utopia, but a realizable reality.