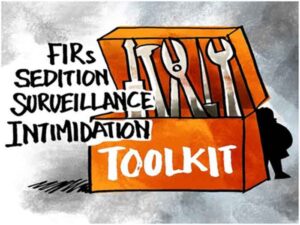

The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, published on 25 February 2021 under the Information Technology Act, 2000 will have a chilling effect on the freedom of expression of ordinary individuals, social media writers and the journalists working in print and electronic media.

The Government of India is trying to usurp the power of Parliament and control the media through the Rules – Rules 2021 replacing the Rules 2011 – and not by statute passed according to procedure.

The ethical norms so far will get converted into penal provisions and the immunity that was given to intermediaries by IT Act 2000 now vulnerable to criminal liability through these Rules 2021.

The Principal Secretary of Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and the minister or government through him will be exercising enormous powers as he would be heading the Inter-Departmental Committee of Secretaries of Central Ministries as an oversight body.

Three UN Special Rapporteurs (a) on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; (b) on the rights to freedom of peaceable assembly and (c) on the right to privacy, expressed their serious concern at the possible chilling consequences of implementing the Rules 2021 replacing the Rules 2011.

The Special Rapporteurs team is of opinion that the Rules 2021 do not appear to meet the requirements of international law and standards related to the rights to freedom of opinion and expression and right to privacy as protected by Articles 17 and 19 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India acceded, in 1979.

Article 19 (3) of the ICCPR says that the restrictions on the right to freedom of expression must be “expressly prescribed by law” and necessary “for respect of the rights or reputations of others” or for “the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals”.

The devil in ‘ambiguity’

The devil dwells in details. A close reading of the Rules 2021 reveal that the restrictions are ‘catch all’ provisions with wide scope and highly ambiguous. The penal law becomes atrocious not because of severe punishments prescribed but because of ambiguity in defining criminality. UN Rapporteurs cautioned against adoption of broadly defined legislation which may result in undue restrictions to freedom of opinion and expression.

Big source of abuse

Whether international law or domestic law, the restrictions must be provided by law (statute passed by legislature) and be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly. In this regard, terms such as content that is “racially or ethnically objectionable”, “harmful to child”, “impersonates another person”, “threatens the unity… of India,” “is patently false and untrue”, “is written or published with the intent to mislead or harass a person […] to cause any injury to any person”, are overly broad and lack sufficiently clear definitions and may lead to arbitrary application.

Most of the terms in the Rules 2021 do not rigorously define grounds for restrictions and fail to provide adequate guidance on the circumstances under which content may be blocked, removed, or restricted, or access to a service may be restricted or terminated, thereby falling short of the legality requirement under international human rights law.

Freedom of speech is not absolute. The Parliament can impose restrictions reasonably on only grounds listed in Article 19(2). Neither the PMO nor the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting imposes any new restrictions through their sub-ordinate legislation like framing of rules.

The Government of India is trying to usurp the power of Parliament and control the media through the Rules and not by statute passed according to procedure.

False, fake, and untrue information

Generally, the restrictions and use of high power from authority is based on a ground of false and untrue information. The UN Special Rapporteurs wrote: More specifically, we would like to underscore that false and untrue information is protected under international human rights law. In its General Comment no. 34, the Human Rights Committee has made clear that the ICCPR does not permit general prohibition of expressions of an erroneous opinion (CCPR/C/GC/34 para. 49)”.

Referring to fake news as a ground for restriction on Media, the UN Rapporteurs said that the Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and “Fake News”, Disinformation and Propaganda published by my mandate and regional experts on freedom of expression, sets out the applicable human rights standards in this context.

While noting with concern that disinformation may harm individual reputations and privacy, or incite to violence, discrimination, or hostility against identifiable groups in society, the Joint Declaration made clear that general prohibitions on the dissemination of information based on vague and ambiguous ideas, including “false news,” are incompatible with international standards for restrictions on freedom of expression, and” should be abolished”.

Another ambiguity is about ‘misleading’ news. If the executive governments exercise power in directing the removal of content that may “mislead” and cause “any” injury to a person is considered excessively broad and can cause selective interference into media from the authorities.

What is needed is specific and precious definition. As social media intermediaries deal with a huge amount of content, a rigorous definition of the restriction of freedom of expression is critical for them to protect speeches that are legitimate under international law, such as the expression of dissenting views. A sufficiently precise definition is essential to prevent the possibility that legitimate expressions is taken down on political or other unjustified grounds. It will ensure that the new rules do not have a chilling effect on independent media reporting.

Leading to removal of legitimate expression

Now, the serious problem in India is that the ruling parties and their governments frequently seek removal of contents called takedown requests. The social media platforms, or intermediary companies must comply with commands of the government to takedown the material from the publication sites.

These companies are under obligation either to develop digital recognition-based content removal systems or automated tools to restrict content.

These techniques are unlikely to accurately evaluate cultural contexts and identify illegitimate content. There are serious apprehensions and worries as to compliances of these commands at the short deadlines, coupled with the criminal penalties that could lead service providers to remove legitimate expression as a precaution to avoid sanctions.

Respecting human rights is an obligation not only on state-actors but also the private companies like social media intermediaries.

The private companies have a responsibility to respect human rights, per the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. However, the outsourcing of content moderation by requiring private companies to remove broad categories of content, without an order of a court or independent administrative authority, may run contrary to international standards on freedom of expression.

Content removals must be undertaken “pursuant to an order by an independent and impartial judicial authority, and in accordance with due process and standards of legality, necessity and legitimacy” (A/HRC/38/35, para. 66).

In this context, the landmark judgement of the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India, of 24 March 2015, wherein it was clarified that content restrictions may only come from a reasoned order from a judicial, administrative, or government body.

It is known to all that the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology directed Twitter to shut down over 1,000 accounts under Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, on 31 January 2021, on grounds that these accounts were spreading misinformation about farmers’ protests.

The UN Rapporteurs and democratic activists in India are worried that the new Rules may provide the authorities with the power to censor journalists who expose information of public interest and individuals who report on human rights violations in an effort to hold the government accountable. We would like to emphasize that the respect for diversity, pluralism and independent information is a necessary condition for the functioning of any democratic society.

The Rules 2021 are potential enough to subject individual employees of companies to criminal liability, which is of serious concern for the international and internal intermediaries in India.

The UN Rapporteurs said “The severity of the envisaged penalties incentivizes the restriction of content and is likely to have a chilling effect on freedom of expression.”

***

Courtesy: Hans News Service, | 22 Jun 2021

Author Dr. Madabhushi Sridhar Acharyulu was a Professor at Nalsar University of Law in Hyderabad, former Central Information Commissioner and presently Professor of Law, at Bennett University, Greater Noida.

Email:professorsridhar@gmail.com