- Islamabad’s bid to make the area its fifth province will at the very least exacerbate military tensions with New Delhi, analysts say

- The gambit will be seen by India and the US as being greatly influenced by China

Pakistan’s government is putting the finishing touches on plans to “provisionally” make the Gilgit-Baltistan region of disputed Kashmir part of the country, risking another high-stakes showdown with India that could lead to war.

Analysts focused on South Asia said the decision to grant interim provincial status to Gilgit-Baltistan – made during a meeting last week between government ministers, opposition leaders and the country’s powerful military – would at the very least exacerbate military tensions between India and Pakistan. The neighbours have fought two wars over Kashmir since attaining independence from British colonial rule in August 1947.

Diplomatic ties were all but snapped six months later, after Modi’s administration revoked the semi-autonomous status of Indian-administered Kashmir and carved out the Ladakh region bordering Tibet as a separate territorial unit.

Analysts told This Week In Asia that Pakistan’s move to make Gilgit-Baltistan the country’s fifth province would be seen by India – as well as the United States – as being greatly influenced by China. The region has been administered by Pakistan, though not fully part of it, since 1947.

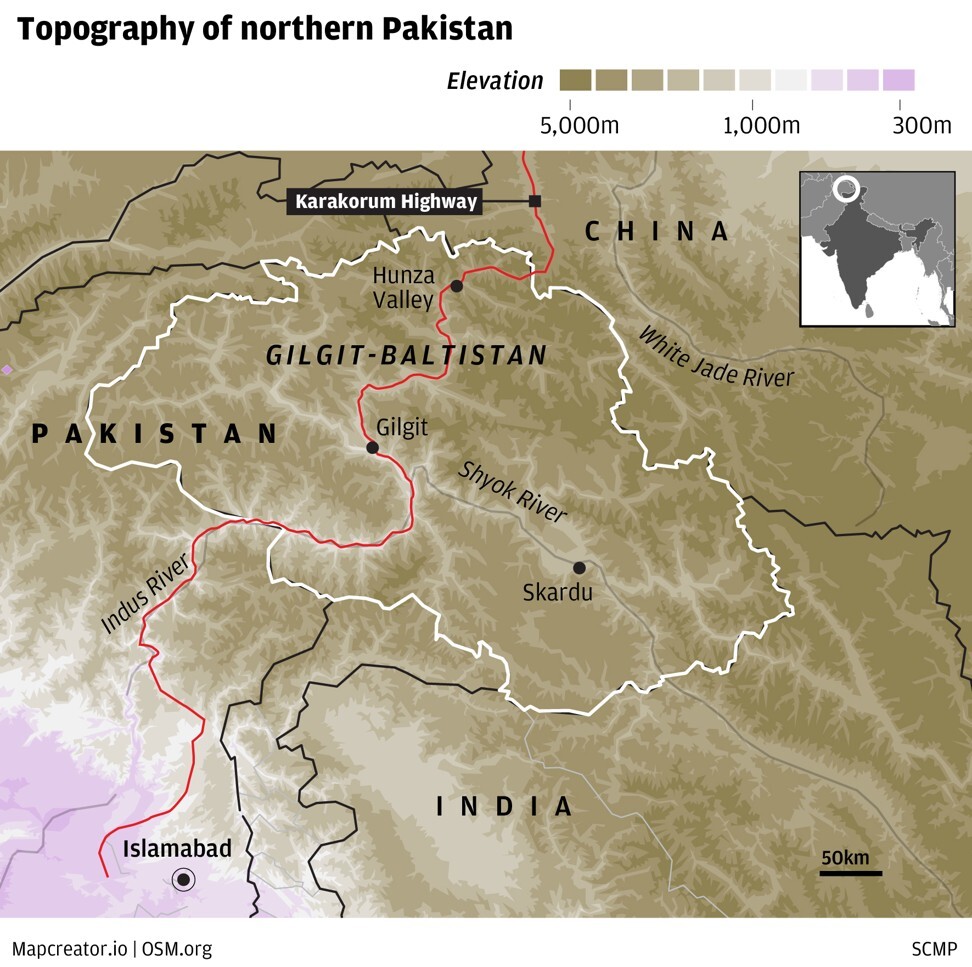

Ladakh is separated from Gilgit-Baltistan only by the Siachen Glacier – notorious from 1984 to 2003 as being the world’s highest active war zone. Most of the world’s 20 highest peaks are located in the region, where the Himalaya, Karakorum and Hindu Kush mountain ranges meet.

TWO-FRONT WAR

Pakistan’s move to change the status of Gilgit-Baltistan would feed Indian apprehensions that it might have to fight a high-altitude, two-front war against both China and Pakistan, the analysts said.

The region is also of key strategic importance to China. Following China’s 1962 border war with India, it struck a border settlement agreement with Pakistan, setting the stage for their close alliance.

and has been China’s sole overland access route to the Arabian Sea, at the mouth of the oil-rich Gulf, since the completion of the Karakorum Highway linking China and Gilgit-Baltistan to the Pakistani hinterland in 1978.

Since 2015, Chinese state-owned enterprises have invested more than US$30 billion expanding and integrating Pakistan’s economic infrastructure along the overland route, which culminates at the Chinese-operated port of Gwadar.

“The Modi government, with its more muscular and nationalistic approach to territorial claims, has spoken often and specifically about its strong claim to Gilgit-Baltistan,” Kugelman said. “I certainly don’t expect the Indian government would simply accept this move by Pakistan as a reciprocation of sorts for India’s … revocation. Rather, it would see it as a provocation, pure and simple.”

Harsh V. Pant, a professor of international relations at King’s College London, said that “by trying to legalise its stranglehold over Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan is trying to not only remove the roadblocks to Chinese investors in CPEC, but also giving Beijing greater access”.

It also made the two-front war scenario “very realistic”, Pant said. “India will certainly read that this is being done at China’s behest and Pakistan has no alternative but to become a casualty of rising Sino-Indian tensions.”

Kugelman said that it would be easy for India and “quite possibly the US” to see a Chinese hand behind Pakistan’s move to make Gilgit-Baltistan a province, “given how free-falling relations between Beijing and New Delhi have given Pakistan and China a fresh incentive to collectively push back against India and to undermine its interests”.

“And what better way to do so than to try to snuff out India’s claim to Gilgit-Baltistan – which also happens to be a key location for CPEC, which India rejects – by turning it into a province,” Kugelman said.

On the contrary, he said it would be wrong to overstate Chinese influence over Pakistan’s decision because it had, for the past 20 years, telegraphed its desire to make Gilgit-Baltistan a province.

“In effect, Islamabad doesn’t need prodding from Beijing to make this move, given that there’s been sentiment to push forward on this for quite some time,” Kugelman said.

THE GREAT GAME

Ejaz Haider, a Lahore-based South Asian strategic affairs analyst and veteran participant in Pakistan’s previous informal “Track 2” dialogues with India, said the Gilgit-Baltistan issue “does not concern any external state actor”.

“It’s an internal constitutional arrangement, fulfilling the constitutional demands of the people of Gilgit-Baltistan,” he said.

Gilgit-Baltistan was not considered part of the Kashmir region until it was seized by British colonial forces in the late 19th century, to pre-empt a feared southward expansion of the Russian czarist empire into colonial India – a geopolitical competition that gave rise to the phrase “The Great Game”.

Historically, the region had little to do with Kashmir or India. Prior to British colonial rule, it was a remote area of warring principalities whose allegiances periodically shifted between Tibet, China and the Muslim empires of the Middle East and Central Asia.

Kashmir was not created until British colonialists “sold” its component territories to an Indian prince, Gulab Singh, in 1846.

Whereas Singh was able to establish the rule of the Dogra dynasty over the easternmost areas of modern-day Gilgit-Baltistan, the rest of the territory – including the areas bordering current-day Xinjiang – continued to be loosely ruled by the British until independence in August 1947.

Whereas Singh was able to establish the rule of the Dogra dynasty over the easternmost areas of modern-day Gilgit-Baltistan, the rest of the territory – including the areas bordering current-day Xinjiang – continued to be loosely ruled by the British until independence in August 1947.The Dogra dynasty did not appoint a governor for what is now Gilgit-Baltistan until July 1947, a few weeks before India and Pakistan became independent.

Gilgit-Baltistan was very briefly ruled by a transitional administration until it quickly communicated its desire to accede to Pakistan. Between 1947 and 1951, it was governed as part of northwest Pakistan.

However, it was subsequently dragged back into the Kashmir dispute under UN Security Council resolutions that laid out a road map for its resolution, following the first India-Pakistan war in 1948-49.

“People of Gilgit-Baltistan have long agitated to be part of Pakistan. Unlike occupied Jammu and Kashmir, where the population wants to secede from India [to join Pakistan], Gilgit-Baltistan wants to integrate with Pakistan,” said Haider, a former Ford Scholar with the University of Illinois’ programme on arms control, disarmament and international security.

RIGHT OF REPRESENTATION

Pakistan’s plans to make the region a provisional province would see its estimated 1.5 million residents granted fundamental rights under Pakistan’s constitution for the first time, including the right to appeal cases to its Supreme Court. Gilgit-Baltistan would also be represented by directly elected members of Pakistan’s National Assembly, and be given the same representation the four mainland provinces have in the indirectly elected Senate.

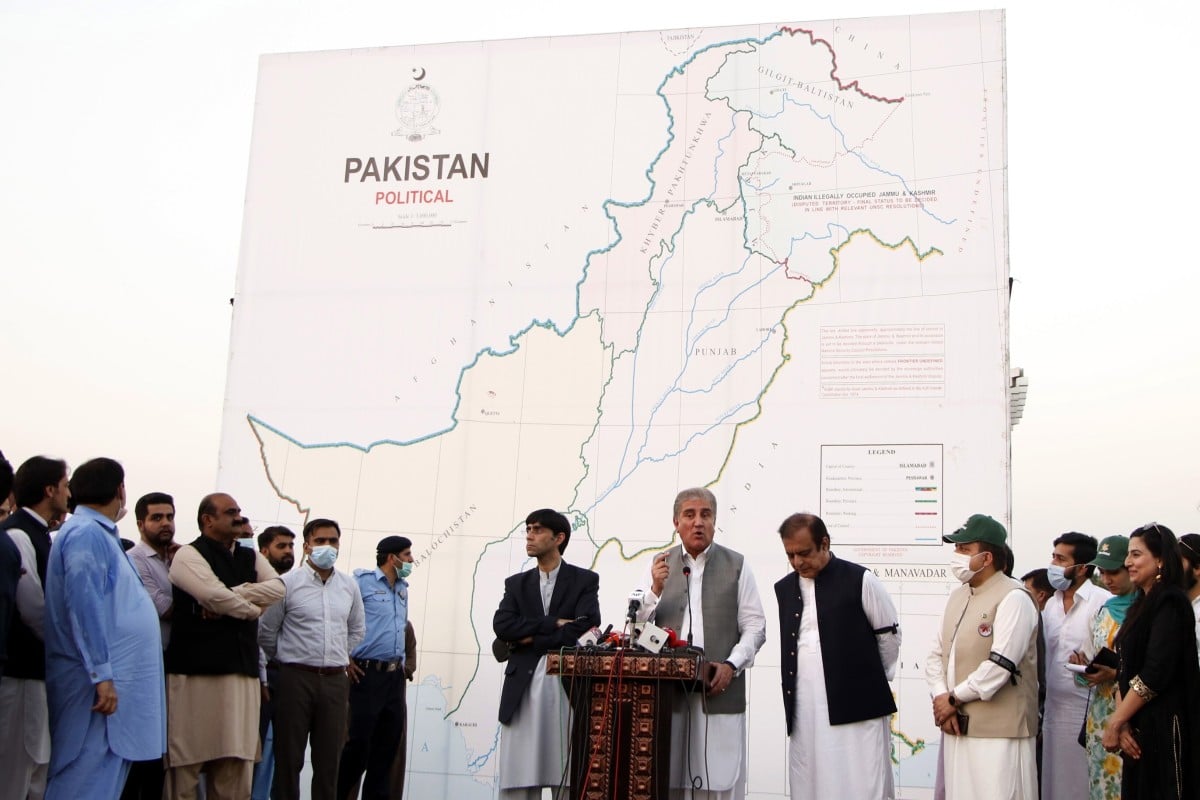

Representatives of parliamentary parties were briefed about the plan at a September 16 meeting with army chief of staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa, held at the Islamabad headquarters of the military’s Inter Services Intelligence agency.

Ministers and opposition leaders said that an agreement in principle had been reached to back requisite changes in Pakistan’s constitution. However, the opposition insisted the process should not be initiated until after elections in Gilgit-Baltistan are held on November 15 – so as to prevent Prime Minister Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) party from cashing in on the move at the ballot box.

The sticking point, according to the chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, will be whether the military interferes to ensure the formation of a PTI government – as it reportedly did in Pakistan’s 2018 general election.

If the outcome is tarnished, the parliamentary opposition easily has the numbers to block the three constitutional amendments required to make Gilgit-Baltistan a provisional province.

Another potential obstruction is the forthcoming launch of an all-party opposition movement in opposition to long-standing military interference in Pakistan’s politics.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani move to make Gilgit-Baltistan a province would “undoubtedly add more volatility to an India-Pakistan-China triangle already experiencing ample churn”, Kugelman said.

He envisioned several impacts: India would have even more motivation to double down along the disputed border with China, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), with heightened prospects for another clash with Chinese troops. And the chance of intensified cross-border firing and ceasefire violations by the Indian side along the LOC with Pakistan-administered Kashmir would increase, he said.

“Amid heightened tensions along India’s two most volatile borders, the risks of miscalculations or escalations would be driven up,” Kugelman warned.

Pant, the King’s College London professor, sees a similar chance of escalation from the Chinese side if Pakistan makes Gilgit-Baltistan a province. “Escalation along the LAC remains a high probability, and few in New Delhi would discount the possibility that Pakistan would up the ante along the LOC at the behest of Beijing,” he said. ■