by Bilal Ahmad Tantray 13 September 2020

Is Huntington’s previously rejected theory of a ’Confucian-Islamist alliance’ making a resounding comeback?

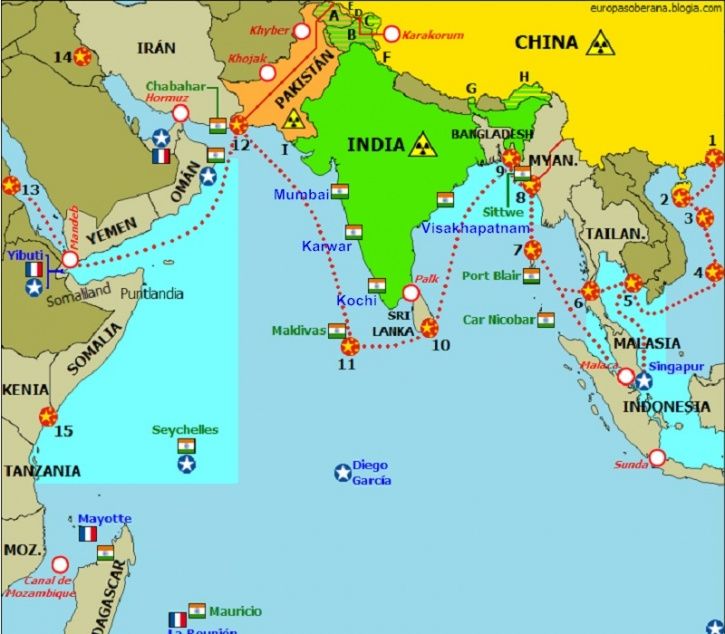

Whenever we hear the mention of the string of pearls, what comes to mind is totally dependent on our academic inclinations. For some of us, it will be a beautiful, cascading, green beaded succulent that naturally occurs in East Africa. But for some who are more familiar with the geopolitical happenings across the world, it is a series of connected ports and naval bases that China is attempting to use for projecting their power and influence in the Indian Ocean. A very few who are familiar with both will recognise the remarkable similarities between the botanical and geopolitical versions of ‘String of pearls’. The String of Pearls (the plant) requires sufficient room for its survival and thriving. Even if it is rooted in a small base, it still needs space where its tendrils can cascade and spread out. So is the case with the Chinese string for it couldn’t stay limited in the seas that surrounded the country. It inevitably needed to cascade into the Indian Ocean where its tendrils can twine around any suitable support. Propagating String of Pearls (the plant) is easy because they have a very shallow root and grow new root quite easily. The easiest way is to do that is to use cuttings. You just need to lay a healthy cutting on the ground and the root will slowly grow out on its own. The same is the case with its Chinese geopolitical counterpart. You just need to lay healthy cutting in the form of investment and expect the roots to develop gradually. And finally, there is another striking feature. The succulent can be toxic when consumed and that is potentially true for the Chinese ‘String’ as well.

In July this year, Iran signed a 400 billion dollar worth deal with China spanning around 25 years. With this, Iran has very overtly joined the China bloc in what is again becoming a bipolar world, or a multipolar one with two very disproportionately large poles. Iran really didn’t have much of a choice as the whole world had turned away from it and the fatigue of the consistent embargo was beginning to show and cause ruptures domestically as was evident from the 2019-2020 civil unrest in the country. The deal also proposes joint training and military exercises, intelligence sharing, joint research in addition to Chinese investments in the two ports along the coast of Sea of Oman. This extends the already long list of ports from the South China Sea to the Red Sea with heavy Chinese investments. Although the extent to which the Chinese influence can be exercised with the help of these ports is often grossly over-exaggerated a long term presence in these ports will surely keep the opponents on the edge.

This axis involving China-Iran-Pakistan was something that was prophetically foreseen by Samuel Huntington as what he called the ‘Confucian-Islamist’ alliance. Huntington predicted that in the 21st century, cultures with common values as is the case with the Muslim societies will come together in civilizational cohesion. He also went on to argue that the western civilization’s hegemony will be contested by a coming together of the Confucian and Muslim civilisations. His prediction regarding the cohesion of Muslim societies to align themselves in unified action doesn’t seem to be in the scope of realisation for now but his envisaging of a China-Iran-Pakistan nexus based on a ‘weapons for oil’ quid pro quo has certainly taken form. The 25-year deal promises oil at subsidised rates to China. This dovetailing of interests may not be so much due to cultural similarities as they are due to the threat of a common enemy I.e. the west. But a deep relation is being engineered nonetheless.

The China-US rivalry has been there for quite some time and has been thrown into sharper relief with the Covid-19 pandemic and now it seems to be on steroids. The US isolationism under Donald Trump has opened the Middle East right up for a new foreign influence. A perpetually energy-hungry China is going to try and make inroads. Bonhomie with Iran which leads the Shia block in the Middle Eastern ‘Cold war’ is a step towards that. Iran on the other hand has been pushed into this alliance by the United States’ unilateral actions and the inaction of the other members of the International community. Even the long term allies like India left its side under US pressure. It was under such circumstances that Iran had to abandon its long term policy of ‘neither East nor West’. Iran’s connection with China although, is not that new. It was during the Iraq-Iran war that the arms supply from China to Iran garnered pace. Also, China is the largest trading partner of Iran and has been so for a decade now. But with recent signing, Iran seems to have given up the balancing act and conspicuously sided with China.

For India, this turn of events is extremely worrying. In the same month in which the Iran China deal was finalised, Iran dropped India from the Chabahar- Zahedan railway project which had been in the pipeline since 2016. This 500 km long project was of great strategic importance for India as it hoped to by-pass the Pakistan clog in the extension of its reach to Afghanistan and Central Asia. It also provided an opportunity for its attaining of energy security by developing unimpeded supply lines across the Arabian Sea, through the Chabahar port and into Central Asia via Afghanistan. The Indian road to Central Asia seems to have been obstructed by a landslide for now as the clouds of the greatest geopolitical reality of the 21st century i.e. the rise of China precipitate down the Persian skies.

Indian Strategists will surely see this as the elongation of the ‘String pearls’ by China which seems to have completely circled India with presence from Djibouti and Tanzania in Africa to Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh in South Asia to Paracel islands and Hainan in East Asia. Chabahar port in Iran was supposed to be India’s counter to the Chinese stronghold of Gwadar but that policy seems to have lost its teeth now. Iran has been a long term ally of India. New Delhi’s friendship with Iran has also been a marker of India’s strategic autonomy. That ship seems to be sailing away for now as well. However, the international scenario is quite dynamic at the moment and we seem to be in a time in history where to say it in Lenin’s words ‘decades are happening in weeks’.

Many intellectuals might also argue that the difference between military or naval base and a port needs to be accounted for while calculating the threat that ‘the string of pearls’ poses. But that would be a gross oversimplification. Gwadar port in spite of the heavy Chinese infrastructure and presence is legally under Pakistani sovereignty and as per the above-mentioned argument, the related threat is hyperbolised. But in case of a military exigency with India, if China requests Pakistan to use Gwadar as a naval base, it is very unlikely that Pakistan would decline that request. Similar will be the case with other ports in other countries that are in strong alliances with China in addition to being under heavy Chinese debt.

In the case of an Indo-China conflict, all these ports are potential bases of a military or a semi-military nature and that should threaten not only India but many other states including the United States.

For the United States under President Trump, the Middle East policy is both murky and crystal clear at the same time. It is crystal clear in terms of who its allies in West Asia are. It strongly stands beside Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the GCC no matter what and has a strong tangible dislike towards Iran and its smaller associates. A change of leadership towards the end of the year may see a reversal of many of Trump’s decisions. US’s withdrawal from JCPOA can be one of the decisions reversed. Joe Biden, the Democrats Presidential candidate has made his intentions of rejoining the JCPOA clear already. However, the overall stance of the US in the Middle East is that of backtracking. With the goal of energy self-sufficiency attained, West Asia doesn’t really hold the importance it did for the US a few decades ago. For China though, the opposite holds true. Their energy needs have multiplied over the years and so have their stakes in West Asia. An unstable West Asia is something that China at this point of time does not want and cannot afford while America with its surplus oil production and an eager European market would not really mind. The United States still controls 1/4th of the world’s GDP and is an unmatched military power but the lead they enjoyed over the others has definitely thinned out and the rest of the world realises that. American policies In Asia and their ‘war on terror’ have caused widespread resentment in the Muslim world. A post-American world will be welcomed with open arms in large fractions of Muslim society. China as the only possible opponent can make inroads and recruit these disenchanted Muslim societies for their own opponent bloc.

For West Asia, the implications are quite complicated. There already is a regional Cold war going on with Iran and Saudi as the main opponents. This war has played out gruesomely in Yemen and also in Syria and Iraq before that. China being the fastest-growing power in the world has naturally been seeking entry into the politics of the region and its economic ties in West Asia have made the ground fertile for that. A close partnership with a leading power of one of the two blocs may be seen as a possible entry point for China into the region. And with the US gradually backing out of the Middle East, a greater Chinese presence is not only possible but also ineludible. The apprehensions about Iran becoming a Chinese client state in the future may seem a little overstated at the moment but geopolitics tends to look a hundred years into the future. The fact of the matter remains that the West has not been on good terms with Iran since the 1979 revolutions. America and its allies irrespective of who is in power have been making consistent efforts to destroy the Iranian economy and this is not exclusive to republican governments. As things stand today, Iran needs China a lot more than China needs Iran, and a country as active in foreign affairs as China will not be oblivious to this fact and will definitely try to take advantage of it.

Conclusion

At the core of Huntington’s Confucian-Islamic alliance theory is the possession of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons and the technological ability to deliver them. That exact thing is at the core of Iran-US contestation as well. Iran’s desire to develop nuclear weapons and US’s discomfort in the Iranian ability to actually do that has kept the two perpetually on the edge. Iran’s alliance with China is no longer a ‘’renegade’s alliance’’ but has now balance of power sensibilities as well as it involves one the two biggest powers in the world. The manner in which the American image has been etched in Iranian memory is very specific. US is the power that thwarted the Iranian stint at democracy in 1953 when the Mosadeq government was overthrown to bring in the autocratic, pro American Shah back to power. On the other hand, the American cognizance of Iran fails to go beyond the 1979 hostage crises. Seeing each other as the enemy has become a part of their respective strategic cultures and these perceptions are very difficult to undo. American attempts to isolate Iran are somewhat in conformation with Iranian perception of itself in the last half century. It views itself as a loner. It surely does not identify with the west. However, it does not identify with the Muslim world either. Iran has been at loggerheads with other Muslim nations like Saudi and UAE. It is the only significant Shia Muslim power in the world. Globally, the Shia Muslims are in a minority and the Shia-Sunni divide has been amplified with the various on-going conflicts in the Middle East where an apparent Cold war is in process and where Iran is the leader and many a times the sole representative of the Shia faction. This very specific identity that Iran dons contains an intrinsic element of isolation. Let’s just say that Iran is not as threatened by isolation as other countries might be. In such a situation running into a Chinese embrace seems like a quick fix for Iran in the short term but in the long run, it may end up being too dependent on Beijing and risk becoming the new Pakistan.

‘The Clash of Civilizations’ has been extensively discussed and predominantly renounced. But it still is a part of the International Politics discourse nearly three decades after it was first published. The dynamism of the modern world doesn’t allow a complete rejection of this theory. ‘Clash of Civilizations’ should be analysed in parts rather than as a whole. Many of its assertions like ‘civilizational rallying’ and ‘kin-country syndrome’ have found very little realisation in the real world. However, some parts of these theories have found feasible substance in the geopolitical realities of the new world. Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’ may experience resurrection through the ‘String of Pearls’ and the ‘New Silk Route’. As CPEC and BRI extend westwards from China, a geographical unification of East Asia and West Asia will come about. The Confucian and Islamic civilizations will come in closer contact and they will be in a position to form stronger alliances. The Chinese wish to see a future where their power and influence is fully spread across the Mackinderian ‘World Island’. Then, they will be in the position to dominate the world. A post American world order is a vision shared by many and the ‘West versus the Rest’ phenomenon is already underway.