BY Hari Prasad Shrestha 20/2/2018

The forcible deportation of a population—is defined as a crime against humanity under the statutes of both International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The official United Nations definition of ethnic cleansing is “rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove from a given area, persons of another ethnic or religious group.”

Under almost all cases of crime against humanity and ethnic cleansing, only African leaders have been investigated. Most African leaders oppose this, while such crimes are in increasing trends also in many countries of Asia and Latin America.

Bhutan forcefully evicted Nepali speaking Bhutanese and compelled them to enter Nepal via Indian territory under systematic and planned strategies indirectly supported by quiet Indian diplomacy, which was criminal precedence, encouraged by alignment with a powerful nation, to its minorities by such a small country.

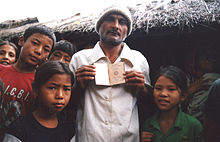

During the 1990s, they deported from Bhutan during the ethnic cleansing carried out by King Jigme Singye Wangchuk; many refugees claim to have been forcibly evicted by the military, who forced them to sign “Voluntary Migration Form” documents stating they had left willingly. Most of the refugees had official proof of citizenship, property papers and passport of Bhutan, which were forcefully ceased by the military. However, some succeeded to bring such documents with them to Nepal.

Around 120,000 Bhutanese refugees arrived in Nepal. They were settled temporarily in several camps in Jhapa in eastern Nepal. The third country resettlement program was launched in 2007, and nearly 111,000 refugees from Bhutan have been settled in various western countries, with the US alone getting more than 90,000 of them. Approximately 2,000 refugees are currently undergoing screening process under the third country final resettlement program. After that the UN it is set to close the third-country resettlement program, and an estimated 8,500 Bhutanese refugees will remain in Nepal.

The Nepal Government is unwilling to absorb any of the remaining refugees and is sticking onto the stand that these refugees should go back to Bhutan. Nepal also knows very well that Bhutan is not going to accept these refugees at any cost. Bhutan did not take back even those refugees who were found to be genuine Bhutanese citizens by the joint verification teams of both countries.

The Bhutanese refugees traveled across Indian territory to arrive Nepal. India SSB forced refugees to enter Nepal; legally India can’t do it since Nepalis and Bhutanese can move across the Indian border freely. India’s actions supported the Bhutanese dictatorship. India’s stand on this issue was that it was a bilateral problem between the Governments of Nepal and Bhutan and thus needs to be resolved bilaterally. Accepting the refugees immediately was also weakness in part of Nepal by allowing them to enter Nepal through India.

There are currently 110,000 Tibetans and 102,000 Sri Lankan Tamils living in India officially as refugees. Thousands of others, from Afghans to Sudanese, can be found across India. In Delhi, there is an ethnic Chin community of at least 5,000 from Myanmar itself. Mostly Christians, they too have fled the brutal discrimination in their Buddhist-majority homeland. It is granting citizenship to more than 100,000 Buddhist Chakmas and Hindu Hajongs who fled to India in the 1960s from Muslim-majority Bangladesh, then part of Pakistan. It has also started naturalizing Tibetans born in India between 1950 and 1987.

However, India did not accept Bhutanese Nepali and now not willing to accept Rohingya Muslims. Bhutanese refugees had similar characteristics of ethnic cleansing with Rohingya refugee. New Delhi wants to deport the 40,000 Rohingya Muslims currently residing in India. Now India is familiar with how difficult to deport Rohingya refugees to Myanmar through Bangladesh as Nepal had a similar experience regarding Bhutanese refugees to deport Bhutan via India. This unbalanced policy of not accepting Bhutanese and Rohingya refugees but accepting others has made more unbalanced South Asia region.

There has been a great degree of dissatisfaction about India’s approach amongst the refugee leaders and Nepal government. The Nepalese government argues that since refugees crossed India before entering Nepal, India is a transit point and thus a party to the whole problem. India’s passive role in this issue became a big disadvantage for Bhutanese refugees and advantage for the government of Bhutan.

If we go through the history of Nepali origin people in Bhutan, the first reports of people of Nepalese origin in Bhutan were around 1620, when a few Newar craftsmen from the Kathmandu valley in Nepal went to make a silver stupa there. Since then, people of Nepalese origin started to settle in uninhabited areas of southern Bhutan. The south soon became the country’s main supplier of food. Bhutanese of Nepalese origin, Lhotshampas, were flourishing along with the economy of Bhutan. By 1930, according to British colonial officials, much of the south was under cultivation by a population of Nepali origin that amounted to some 60,000 people.

In the 1940s, the British Political Officer Sir Basil Gould was quoted as saying that when he warned Sir Raja Sonam Topgay Dorji of Bhutan House of the potential danger of allowing so many ethnic Nepalese to settle in southern Bhutan, he replied that “since they were not registered subjects they could be evicted whenever the need arose.” Furthermore, Lhotshampa were forbidden from settling north of the subtropical foothills.

The Citizenship Act of 1985 clarified and attempted to enforce the Citizenship Act of 1958. The basis for census citizenship classifications was the 1958 “cut off” year, the year that the Nepali population had first received Bhutanese citizenship. Those individuals who could not provide proof of residency before 1958 were adjudged to be illegal immigrants. After dissatisfaction seen in the immigrants, amnesty was also given through the Citizenship Act of 1958 for all those who could prove their presence in Bhutan for at least ten years before 1958. On the other hand, the government also banned further immigration in 1958.

Bhutan after the country carried out its first census in 1988. The government, however, failed to properly train the census officials and this led to some tension among the public. Placement in the census categories which ranged from “Genuine Bhutanese” to “Non-nationals: Migrants and Illegal Settlers” was often arbitrary and could be arbitrarily changed. In some cases, members of the same family have been, and still are, placed in various categories; some admittedly genuine Bhutanese have been forced to flee with family members the government found to be illegal immigrants.

Bhutan was in complete preparation to deport Nepal origin population by accusing them as they wish. Its showed concern to avoid a repeat of events that had occurred in 1975 when the monarchy in Sikkim was ousted by a Nepalese majority in a plebiscite and Sikkim was absorbed into India. To resolve the inter-ethnic strife, the king of Bhutan made frequent visits to the troubled southern districts, and he ordered the release of hundreds of arrested “anti-national.” He also expressed the fear that the Nepalese might lead to their demand for a separate state in the next ten to twenty years, in much the same way as happened in the once-independent monarchy of Sikkim in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, Bhutan introduced the policy of “one nation, one people” and alienated the Lhotsampa (Nepali) culture through inter-ethnic marriage between Nepali and Bhutanese, wearing Bhutanese national dress to all and discontinue the Nepali language from schools in Bhutan were causes of dissatisfaction to Nepalese. This was followed by a revision of citizenship laws. Many Nepali found they did not qualify and in the early 1990s, many were forced to leave, reaching the border with India.

However, these measures combined to alienate the majority of bona fide citizens of Nepali descent. Some ethnic Nepalese began protesting perceived discrimination, demanding exemption from the government decrees aimed at enhancing Bhutanese national identity.

Before mass deportation in 1990, between 2,000 and 12,000 Nepalese were reported to have fled Bhutan in the late 1980s, and according to a 1991 report, even high-level Bhutanese government officials of Nepalese origin had resigned their positions and moved to Nepal.

In November 1989, Tek Nath Rizal was allegedly abducted in eastern Nepal by Bhutanese police and returned to Thimphu, where he was imprisoned on charges of conspiracy and treason. He was also accused of instigating the racial riots in southern Bhutan. Rizal was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1993.

After his sentencing, the King of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, pardoned Rizal on condition that Bhutan and Nepal be able to resolve the issue over the certain Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. The issue was not resolved, but Rizal was released from prison during an amnesty granted by the king in December 1999. Rizal attributed his release to the efforts of activists from around the world who pressed for his release, and he has since settled in Nepal.