By Ben Joseph

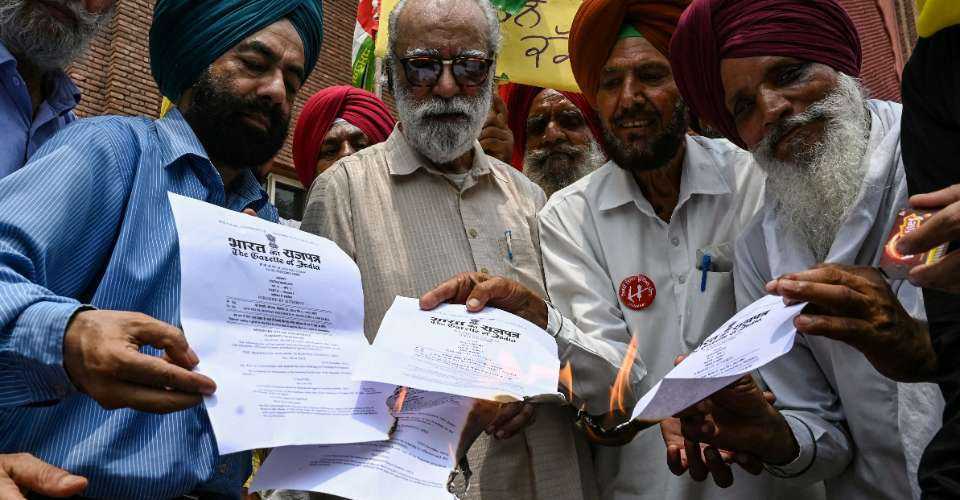

India’s revised criminal code, which came into effect on July 1, replacing the British-introduced Indian Penal Code, has increased the number of crimes that can attract the death penalty from 11 to 15.

Indian laws stipulate capital punishment for more crimes, while rights groups and pro-life campaigners across the world, including those in the Catholic Church, seek to abolish the death penalty, deploring it as state-sanctioned brutality.

The death penalty in India is execution by hanging. India’s rigid legal system and civil society’s reluctance to campaign openly against capital punishment have made the noose so tight that more than 500 people remain on death row in Indian jails.

India’s law commission, in a 2021 report, briefly recommended the abolition of capital punishment for all crimes, save the crime of waging war on the nation and terrorism.

The latest death penalty case discussed in the Indian media attracts special attention to see why campaigners have become reluctant to oppose capital punishment in India.

On June 12, President Droupadi Murmu rejected a mercy petition from Pakistani “terrorist” Mohammed Arif, convicted in the 24-year-old Red Fort attack case in the national capital, New Delhi.

Demonstrating India’s firm stance on continuing with the death penalty, the top court dismissed an appeal by him in November 2022. Now, the hangman’s noose awaits Arif, a Muslim by faith.

Arif, a member of the outlawed Lashkar-e-Taiba, was found guilty of conspiring with other “militants” to attack soldiers stationed at the Mughal-era monument in December 2000. Three soldiers were killed in the Red Fort attack.

Even those advocating the abolition of the death penalty, including Church leaders, have not campaigned to stop the hanging of Arif because of the sensitivity attached to his nationality, religious faith, and the nature of the charge.

Pakistan is considered India’s arch-rival, and in India’s unique Hindu-dominated socio-political reality, asking to save a Pakistani Muslim like Arif could be portrayed as an anti-national act. Moreover, Arif was accused of terrorism against the nation. Openly supporting the life of such a person would have serious social repercussions.

It is almost impossible for the social majority in India to understand the immorality of capital punishment as long as they link vengeance and justice. Social education needs to become primary in the campaign against the death penalty.

The Pakistan national was left high and dry despite the United Nations’ crusade against capital punishment gathering steam in many nations, including those in Africa. When the UN was set up in 1945, the death penalty was abolished in only eight nations, but that number rose to 170 when Ghana became the latest country to ban the inhumane act in 2023.

Capital punishment in India is pronounced after conviction by a court of law. The Indian courts see it as reinforcing the moral indignation of citizens. Thus, the courts put the ball in the court of citizens and make them accomplices in state-sponsored murder. This sends the wrong message to teens and kids.

The death penalty completes a preventive function and is considered a deterrent against serious crimes like rape, murder, and treason. Indian supporters of the death penalty argue that keeping a person in jail amounts to draining public finances and say that capital punishment has a deterrence effect on the general public.

The teaching of the Church opposes capital punishment, primarily stressing that God is the giver of life and man has no right to take it. It also holds death ends all possibilities for a criminal to repent, change and compensate for his crime. The Church sees the right to change as a fundamental human right.

By sticking to capital punishment, the Indian legal system, a remnant of its colonial past, believes that a criminal remains in the same state of mind in which he/she committed the crime.

India is retaining the death penalty by hanging because it will be used only in the “rarest of rare cases.” However, the Indian legal system has not spelled out what constitutes the rarest of the rare.

In India, court proceedings and lengthy appeals are costly. In India’s case, perpetrators from racial and ethnic minorities suffer compared with those tracing their roots to a privileged background.

Less surprisingly, a majority of the death row convicts are from the marginalized strata of society in India, which has 561 prisoners on death row at the end of 2023, the highest since 2004.

Retribution is, after all, a sanitized form of vengeance that legitimizes the very act that the law seeks to arrest. Civil society groups and human rights activists should give up their pick-and-choose policy when it comes to the death penalty. To eradicate the barbaric act of state-sponsored killings, no stones should be left unturned.

source : uca news

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published