By Akash Sahu 29 May 2021

The National Unity Government (NUG) of Myanmar, operating in exile against the military junta or ‘Tatmadaw,’ has announced a ‘People’s Defense Force (PDF)’ as its military wing to help overthrow the junta regime. The Tatmadaw has continued a harsh crackdown on pro-democracy protestors, killing at least 750 citizens since the coup in Feb 2021. While there have been doubts over the formidability of PDF, considerable resistance to the junta regime can be anticipated. If the two sides engage in an armed conflict, a full-blown civil war will threaten the security of the entire region, considering Myanmar sits at the junction of South, Southeast, and East Asia on land and overlooks some of the busiest trade routes in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

As a regional power, India’s role is pivotal in averting a major crisis. However, considering that COVID-19’s second wave has debilitated the country and caused massive casualties, India’s will to be directly involved in Myanmarese affairs can be minimal. Among Indian strategic circles, there is also a belief that Myanmar needs India to balance China’s economic domination. But a violent struggle between the NUG and junta may result in a vast refugee exodus, eventually roping India into the conflict and creating long-term demographic and security problems in its north-eastern region. Geopolitical concerns may have to be reassessed to prevent further deterioration of regional security.

Instability Will Persist

The ethnic Bamar-dominated NUG and the junta are pitted against each other in a national struggle for power in Myanmar. Notably, the NUG is composed of members from the ousted National League for Democracy (NLD) government and protest leaders and representatives of ethnic minority organizations. Myanmar’s central government has largely only controlled the mainland since independence. It has fought ethnic minority armies in border areas and attempted to pacify them through temporary ceasefires devoid of any actual political settlement. Since the coup, the junta is being challenged by the Northern Alliance composed of many ethnic armies like the TNLA, MNDAA, KIA, and AA. The junta forces have also suffered casualties from the Karen National Union’s KNLA in Karen State.

The principle of non-interference, core to ASEAN multilateralism, has prevented a collective ASEAN action against the junta regime. Tatmadaw leader General Min Aung Hlaing has seemingly ignored the five-point peace resolution agreed recently among ASEAN nations in Jakarta as the junta continues to attack civilians in Myanmar. Even as the PDF falls short in strength and armed support before the junta, a long protracted violent struggle between the two sides can be expected.

India-Myanmar Relations

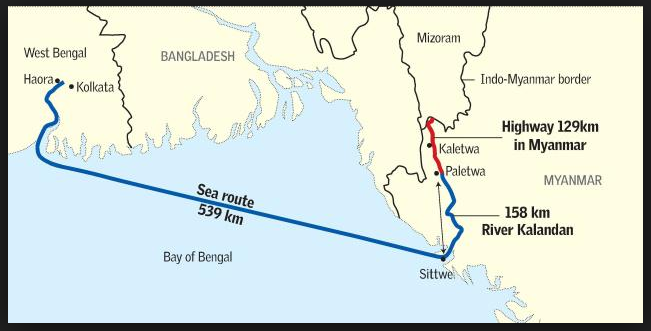

To prevent Myanmar from falling completely into the ambit of Chinese influence, India began engagement in the 1990s. Bilateral relations improved as the Indian Army and the Tatmadaw conducted joint insurgency operations. In the 2010s, the Tatmadaw became vital for India’s counter-insurgency operations on its north-eastern borders with Myanmar. The robustness of ties with the junta is reflected in the apparent ‘permissive hot pursuit’ given to India. A violation of territorial sovereignty may be overlooked (and denied) to achieve an important security objective. Scholars believe the junta is much more troubled with Myanmar’s other borders and hence doesn’t mind such an arrangement with India. Security in the border regions and northeast India is paramount for Indian infrastructural projects like the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, which would connect Kolkata with Zorinpui in Mizoram only via Sittwe port in Rakhine State and Paletwa water terminal in the Chin State of Myanmar.

Additionally, China’s resolve to gain direct access to the Indian Ocean through its Kyaukpyu deep-sea port project in Myanmar is also a pressing security concern in New Delhi. China’s heavy investments and influence in Myanmar cautions India against hasty action. Journalist Bertil Lintner in his book ‘The Costliest Pearl,’ explains how, on the one hand, China has cultivated profound relations with the junta government, but on the other hand, tries to manipulate it through the United Wa State Army (UWSA) to protect its interests. Heavily armed by China, UWSA is the most powerful constituent unit that survived the erstwhile Communist Party of Burma.

India’s Options

India has called for the restoration of democracy in Myanmar, but sending an envoy for the junta’s military parade has sent mixed signals. Clearly, India is mindful of not antagonizing the junta. Even as the country is rallying behind Aung San Suu Kyi, the past few years have shown that she is hardly an inclusive or liberal leader. Her closeness to Beijing has also possibly irked India. The nationalist junta has created a balance of sorts between Chinese and Indian influence in Myanmar, trying to take the most advantage. More than any foreign power, the junta eyes Suu Kyi with suspicion and deems her incapable of understanding risks to Myanmarese sovereignty due to greater dependence on China. India, most probably, shares the same assessment of her.

However, if Myanmar gets embroiled in civil war, a large refugee influx would destabilize India’s northeastern territory and potentially revive insurgencies minimised with consistent effort. It would be unwise to ignore a fast-evolving crisis in the neighbourhood, especially as Myanmar is seen as India’s gateway to Southeast Asia. It would also be a flawed policy measure to offer unconditional support to the junta government because that seems to be driving popular opinion in Myanmar against such countries. China blocked the UNSC resolution condemning the coup, and about 32 China-backed factories were burnt down in March. Recently, security guards at a Chinese pipeline station in Mandalay were brutally attacked and killed. Whether Suu Kyi or not, ensuring that Myanmar’s objective public opinion is favourable should also factor strongly in India’s policy calculus.

Taking sides in the Myanmar struggle for any external power can have two-prong effects- Firstly, it could polarize the NUG and junta to no end, making it difficult for them to come to any arrangement in the future; this is evident from several cases of internal conflict in Arab nations. Secondly, it could massively increase on-the-ground escalations leading to large-scale destruction of life and property. Alternatively, India can work on its close ties with the junta to stop the violence and bring all parties to the negotiating table, including the NUG and ethnic factions. Indian efforts in Myanmar may be perceived as interference by countries like China. But the seemingly twilight phase will be gone if timely steps are not taken and soon leave much lesser room for diplomacy.

A power-sharing arrangement among the concerned parties in a representative democracy could be envisioned. India’s hard-earned relations with the junta can be utilised to reach a consensus among warring factions. Although India’s military support to oversee a just transition into such an arrangement could be helpful, it is a step too far as the current Myanmar constitution prohibits the presence of any foreign troops on its soil. Enabling a truce among the junta, NUG, and ethnic minorities for a shared vision of Myanmar seems to be India’s best bet to keep the country from becoming an active war zone in the middle of the Indo-Pacific.

The author is a researcher in Indo-pacific geopolitics, security, and balance of power. He currently works at the New Delhi-based think tank Council for Strategic and Defense Research (CSDR) on India’s National Security. He has earlier worked at Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) on Southeast Asian Studies.