To contain the spread of Covid-19, India’s prime minister announced a lockdown for 1.3 billion people as of March 25 with four-hour notice. For millions in India’s cities and towns, jobs vanished overnight, along with access to shelter and food. “The pandemic exposed precarious living conditions for the nation’s poor in overcrowded shanties where social distancing and handwashing sound like a cruel joke,” writes journalist Neeta Lal. “More than 80 percent of the country’s workforce toil in the informal economy, reports the International Labor Organization, and as many as a third of the country’s population are internal migrants.” The lockdown also exposed India’s minimal investment in health care and other social protections for a population representing one out of every six people in the world. Many migrants had little choice but to walk hundreds of kilometers to home villages, joining crowded public transport, if lucky, or waiting in makeshift shelters. The exodus, combined with a lack of resources, may have helped spread the disease. Lal urges the government to prioritize inclusion of migrants in the formal workforce, along with other social protections. – YaleGlobal

India’s Migrant Labor Pains

India’s Covid-19 lockdown exposed precarious lack of social protections for millions of migrant workers – and may have helped spread the disease

Neeta Lal Tuesday, June 9, 2020

NEW DELHI: An exodus of migrant laborers have fled India’s cities – the old and the frail, walking with sticks; couples struggling with infants and luggage, sobbing children trailing behind, trudging hundreds of kilometers on highways back to their native villages.

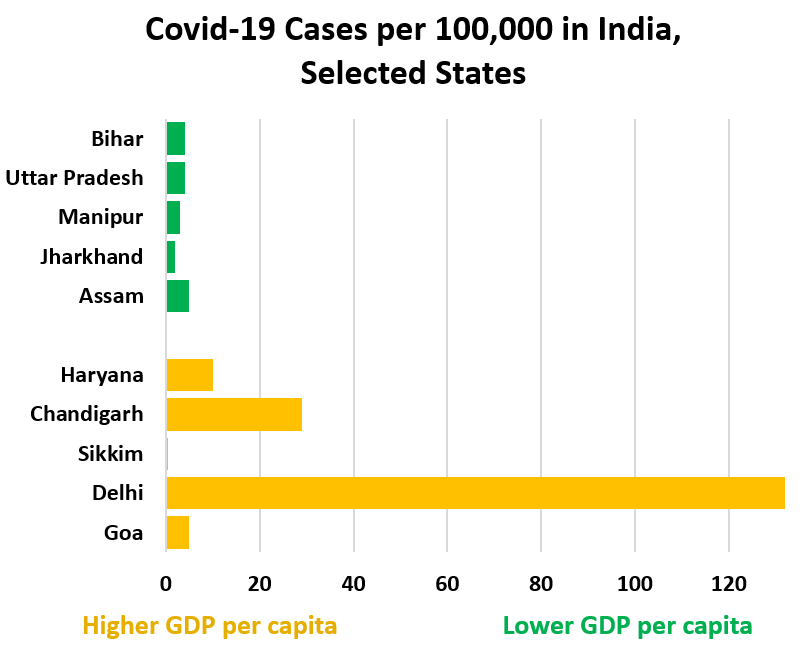

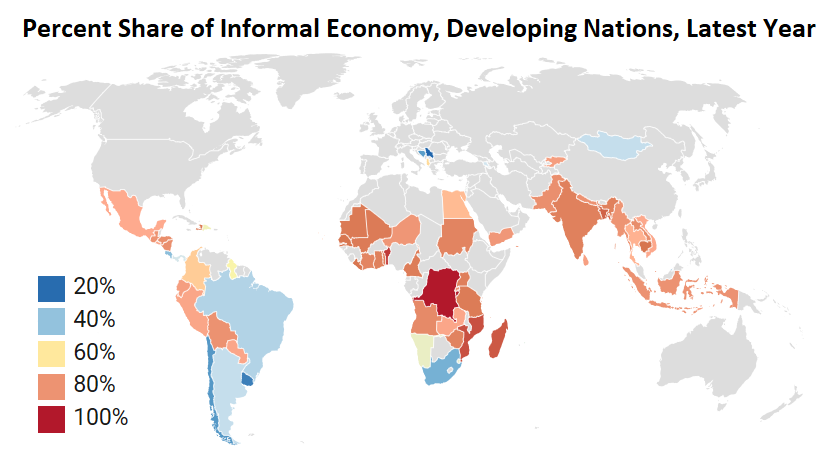

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a national lockdown to control the Covid-19 pandemic, with four hours of notice, confining 1.3 billion people to their homes. The pandemic exposed precarious living conditions for the nation’s poor in overcrowded shanties where social distancing and handwashing sound like a cruel joke. More than 85 percent of the country’s workforce toil in the informal economy, reports the International Labor Organization, and as many as a third of the country’s population are internal migrants

The move may have exacerbated Covid-19’s spread. Millions of poor migrants defied the order to stay indoors. With factories and businesses shuttered and no jobs, savings or social security benefits to cushion them, this disempowered demographic made an exodus from cities where they could not afford food.

Many migrants come from less developed states like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand and Odisha to escape poverty or conflict to work as seasonal labor in urban factories. They build roads, elegant malls and houses or pull rickshaws, clean homes or work as vendors to keep the wheels of the informal economy turning. They contribute 50 percent of India’s national income and constitute nearly 30 percent of the human capital base of the country, according to the government’s Economic Survey 2018-19.

Experts fear the humanitarian crisis will push this segment further into penury, as noted by the International Labor Organization in a report on Covid-19 and migration, warning of “catastrophic consequences” for about 400 million people working in India’s informal economy. A World Bank study on the same topic is equally grim: “Lockdowns, loss of employment, and social distancing prompted a chaotic and painful process of mass return for internal migrants in India and many countries in Latin America.” The bank exhorted the Indian government to include internal migrants in health services, cash-transfer and other social programs, while protecting them from discrimination.

Though the central and state governments responded to the crisis by rolling out a ₹1.7 trillion package, or US$23 billion, as well as some direct cash benefit transfers, thousands complain they cannot access these schemes. Civil-society activists and policy analysts slam the fiscal package as woefully inadequate. “Every other country hit by the COVID-19 pandemic has done more for its poor and working people than the Indian government,” suggests Brinda Karat, former Rajya Sabha member of parliament, deploring the government for writing off bad loans, primarily for corporations, and not saving the poor from starvation.

Indian economist and Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee also offers scathing criticism. “India hasn’t discussed a large enough package,” he noted in a video exchange with Congress parliamentarian Rahul Gandhi. “We are still talking about 1 percent of GDP. The US has gone for 10 percent of GDP.”

Following widespread public outrage over the government’s tight-fisted response, Modi announced a second package of $ 277 billion. However, economists suggest the tranche caters more to long-term uplift of the economy through fiscal measures rather than put cash in the hands of the desperately poor. Analysts scrutinizing details provided by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman concluded that the additional spending boost is far less than the 10 percent of gross domestic product as the government suggested.

Wary of bad optics, some state governments scrambled to provide succor to the needy, organizing trains and buses to ferry them back to hometowns. However, this move soon became mired in controversy due to lack of clarity on who would pay – the governments announced that the journeys would be free, yet migrants showed receipts for full payments, and the endeavor presented an image of running migrants out of communities.

Some employers did not want to lose workers. The government abruptly cancelled special trains from the southern state of Karnataka returning thousands of migrants stranded by the lockdown, expressing concern that construction activities resuming in the state would need workers. This triggered a furor, with critics lashing out at the government for treating migrants like “bonded labor.” Authorities rescinded their decision.

A “PM Cares Fund” launched on March 28 with public donations to bolster relief efforts during the pandemic, and critics questioned why the $2-billion corpus wasn’t utilized to facilitate rescue and rehabilitation for migrants. “Ironically, while India has numerous policies for social security for education, healthcare, skilling, food security and pensions for the organized sector, migrant labor is proffered no such benefits,” asserts Prateek Mittal, economist and author. “This glaring asymmetry has been exposed in the current emergency.” He adds the social welfare scheme, Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi, guarantees farmers US$84 per year as minimum income support and crop insurance, yet such provisions exclude migrant workers.

The most enduring image from the protracted Covid-19 confinement is thousands of migrant workers across the country pushed into overcrowded shelters hastily erected by state governments, civil society groups and employers. Lekhi Ram, 32, stuck at a shelter in New Delhi after March 29, waited to rejoin his wife and four children after losing his job at a garment factory that closed in March. “Whatever money I saved has been spent on buying food,” he explained. “I called the government helpline after which an NGO volunteer gave me some ration of rice, edible oil and vegetables. But now, I just want to go back home.”

Migrants complain of unhygienic conditions inside the camps and little enforcement of social distancing, triggering fears of the infection spreading rapidly among this vulnerable group.

The tragedy is largely the result of an inept bureaucracy and lazy policymaking, conclude analysts, reflected in inadequate internal data on migrants: “official statistics… mainly come from the dated census reports that define a migrant – as a person who lives somewhere that is not their place of birth or their last place of residence,” write Aditi Ratho and Soumya Bhowmick for the Observer Research Foundation. Most migrants lack ration cards or the cards carry domicile restrictions. For migrant laborers no longer living in the state where the card was issued, regulations prevent access to subsidies.

The duo recommend launching a drive to collate up-to-date data on migrants within states to gauge the funds required to provide them with food supplies, housing, sanitation and financial services – currently inaccessible for seasonal migrant workers.

Bolstering India’s abysmal spending on health could can help ameliorate the suffering. In the Union Budget of 2020-21, total expenditure marked for health is 1.29 percent of gross domestic product. This amount compares poorly with other BRICS nations: Brazil, 9.2 percent; South Africa, 8.1 percent; Russia, 5.3 percent; and China, 5 percent. Developed nations spend more: the US, 16.9 percent; Germany. 11.2 percent and Japan, 10.9 percent.

After addressing the Covid-19 crisis, the government’s long-term goal should be to bring greater numbers of migrants into the formal workforce. Mittal concludes that would “provide a robust social security architecture, ensuring access to healthcare services, short-term relief for loss of income, and compensation for occupational hazard and provision of food through the public distribution system.”

Unemployment in India is about 6 percent with youth unemployment at 10 percent. Data compiled by Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy shows a massive jump in weekly unemployment rate following the lockdown. Experts say this could be the result of the migrant workforce fleeing cities with no assured source of income as economic activity ground to a halt. India’s economy and many ruined livelihoods won’t heal soon.

Neeta Lal is a New Delhi-based editor and journalist.

The article appeared in the YaleGlobal online on 9 June 2020

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published