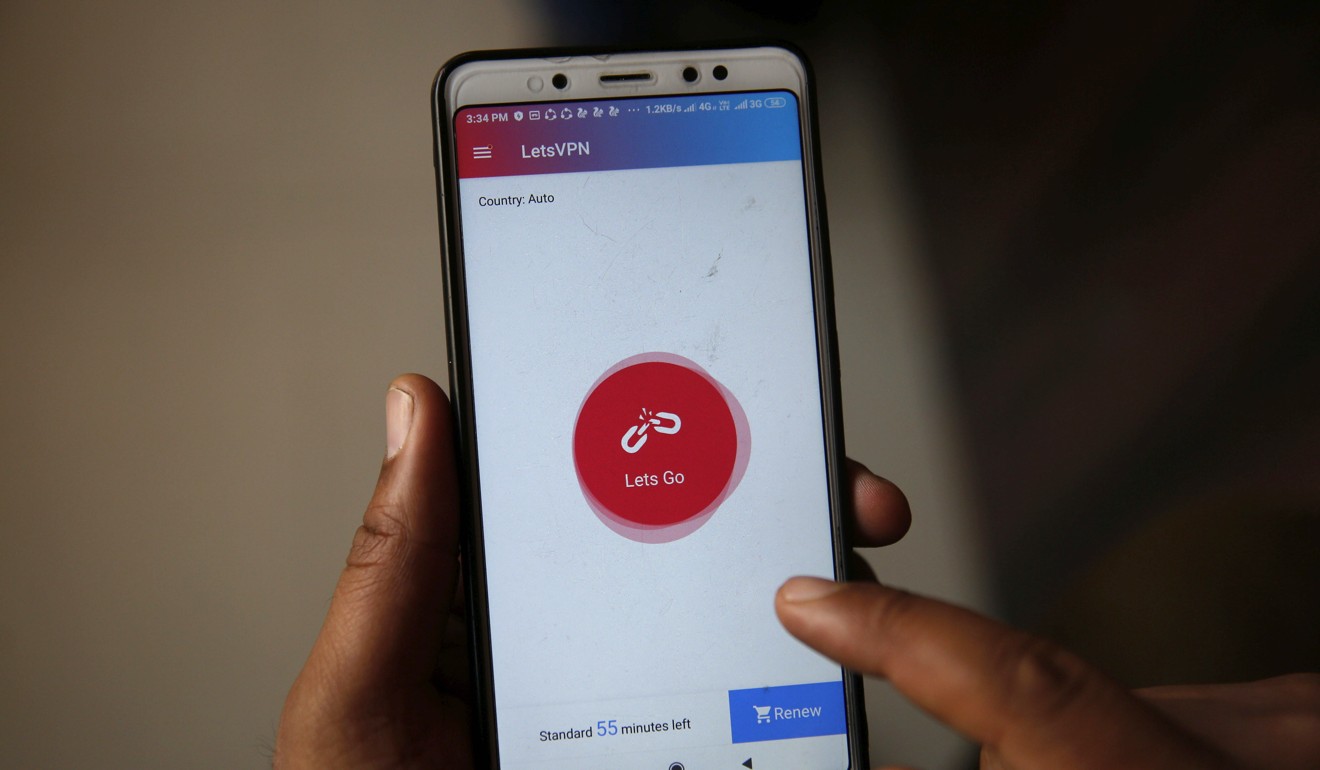

- In order to bypass a ban on social media use, Kashmiris are using VPNs, risking prosecution under anti-terrorism legislation

- Amnesty International has urged the Indian government to ‘let the people of Kashmir speak’

29 Feb, 2020

Indian government has launched a major crackdown in Jammu and Kashmir against internet users who access blacklisted social media sites through virtual private networks in defiance of a temporary government ban on social media, throwing the Indian-administered part of Kashmir into further turmoil.Kashmir had been without internet access since August 5, when New Delhi annulled the Muslim majority region’s limited autonomy to bring it under direct federal oversight. On January 26, authorities restored a slow-speed, censored version of the internet, with only a few hundred websites available for viewing.

To overcome the ban on social media, many Kashmiris have resorted to using VPNs – proxy servers that circumvent the Indian government’s firewall and give Kashmiri users full access to the internet through proxy connections in other countries. But using VPNs now could invite prosecution under India’s recently amended anti-terrorism law.

At least that was the message received by Kashmir residents last week when the police opened a case under the anti-terrorism law against 10 people who they say had “defied Government orders and misused social media platforms” through VPNs, according to a police statement.

According to reports in the local press, police are also investigating at least a thousand other VPN and social-media users for “creating chaos and confusion” and “glorifying militancy and secessionism”.

Authorities have registered the case under India’s broadly worded terrorism legislation – the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, which was enacted in 1967 but amended and strengthened last August.THIS WEEK IN ASIA NEWSLETTERGet updates direct to your inboxSUBSCRIBEBy registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy

It is the first case registered by the newly rechristened cyber division of the region’s battle-hardened police, headed by Tahir Ashraf, an officer who is simultaneously tasked with overseeing counter-insurgency operations.

Those found guilty of violating the ban on social media face up to seven years in jail, according to Amnesty International India.

TARGETING ‘MISCREANTS’

Authorities in Indian-administered Kashmir have repeatedly cited security vulnerabilities to justify blanket bans on communications, including internet censorship. The police statement said that the temporary ban on social media had been ordered “to stall the rumour-mongering and spreading of false and fake facts, having the effect of causing social instability”, and it included an appeal to Kashmiris from the chief of police to not use VPNs, which fall under the ambit of illegal activity.

On the sidelines of a press briefing held after the killing of three separatist militants days after the case was registered, the chief of police in the Kashmir zone, Vijay Kumar, said that among those accessing social media despite the ban were “miscreants” who were “using social media to spread rumours and instigate people, and some were facilitating militants to throw grenades”. Such persons, Kumar said, would be arrested.

The director of police in the region, Dilbagh Singh, said police were aware of the widespread use of social media through VPNs but were only questioning those who “misused” social media.

Netflix OK, but not Twitter: India partly lifts Kashmir’s internet ban25 Jan 2020

In the eyes of the police, though, “misuse” is tantamount to the broad support of secessionism or the glorification of militants. Kashmiris fear that even uploading a picture of a militant on a social media site could be interpreted by police as constituting misuse, as could any criticism of the government.

Singh added that the police were monitoring social media sites and had proof that some Kashmiris were using the sites to coordinate militant activity.

At a tea shop in Kashmir’s largest city, Srinagar, the chatter in a corner suddenly turned grim when the waiter informed two young male customers that police officers in the vicinity were randomly checking phones. “They were right outside as well,” he said with a hint of caution. “They were checking phones for VPNs and reprimanding those who had it.”

Upon hearing the news, the customers deleted their VPN apps, leaving one VPN app available for emergency use and counting on quick reflexes to delete that, too, should they be frisked by police. Moments later, one of them – hurling curses at the government – deleted his last VPN app after discovering that it could no longer bypass the government’s firewall.

AN ARBITRARY BAN

For one Kashmiri research scholar, who uses social media mostly to stay in touch with loved ones abroad, the ban has proven to be not only arbitrary but dehumanising.

“There is nothing in definitive terms that the state has said on the use of this act against people for using social media and it has been left for people to make sense of the situation, the act and use of social media and its consequences,” said the woman, who requested anonymity out of fear of being formally reprimanded by the police and her university.

Avinash Kumar, the executive director of Amnesty International India, said in a statement that while the government “has a duty and responsibility to maintain law and order in the state,” randomly checking people’s phones and “filing cases under counterterrorism laws … over vague and generic allegations and blocking social media sites is not the solution.”

“The Indian government needs to put humanity first and let the people of Kashmir speak”, Kumar said.

Beaten, stripped, lips sewn up: troops trample on human rights in Kashmir8 Jan 2020

Social media awareness in Kashmir emerged around 2008 during protests that began with the transfer of forest land in an ecologically sensitive zone to a religious trust. It was in widespread use as a medium of protest two years later after the killing of three Kashmiri civilians by six Indian troops, who were later convicted by a military court for the wrongful deaths of the Kashmiris. The Indian Army had initially claimed the Kashmiris were Pakistani infiltrators.

The spreading of anti-government and anti-police protests to the digital realm gave many Kashmiris a platform for voicing their dissent or simply to vent their frustrations.

“It not only gave people a [way to] vent but also brought many others to openly express thoughts online,” a Srinagar resident in his 30s who refused to be identified said about the spread of online protests.

“Post-social media Kashmir was on the same page – someone in south Kashmir could read the thoughts and experiences of a fellow Kashmiri in the north and relate to it,” he said. “It built solidarities and shaped public opinion too.”

The northern region of Indian-controlled Kashmir was earlier where the militancy was at its peak, while the south was relatively calmer. Today, the militancy is largely concentrated in the southern region while the north is comparatively calm.

The pervasive influence and potential of social media for disruption began unnerving Indian authorities in 2014, when separatist militants, who come from the ranks of a generation groomed in open defiance of the state, began using social media without trying to hide their identities, spreading militant ideologies and justifying their reasons for fighting the Indian state.

ONLINE WAVE OF SYMPATHY

The flood of separatist content online arguably led to a wave of sympathy for the militants – who are fighting a guerilla war for independence of the region or its merger with the state of Pakistan – by everyday Kashmiris, who themselves had grown tired of government heavy-handedness. Since then, the authorities have remained wary of the impact of social media and its ability to reach a mass audience instantly.

The use of social media was first banned in Kashmir in early 2017, just months after another civil uprising had ended in 2016. That ban lasted for a few weeks before it was withdrawn without much explanation by local authorities.

Now that the federal government has taken control of Kashmir, though, Indian authorities have seemingly locked horns with a civilian population intent on continuing to use social media and VPNs, despite the threat of prosecution.

Kashmir’s special status only fuelled its real problem: Islamism19 Nov 2019

The New Delhi-based advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation has termed the prohibition of VPNs in Kashmir as unlawful and the punishment as disproportionate, and has sent representatives to the Indian government challenging the prohibition.

Apar Gupta, the foundation’s executive director, said that in restricting internet access in Kashmir and implementing bans on social media and VPNs, the Indian government was viewing internet use in the region only through the prism of security.

“This brings a high amount of state discretion to shut down the internet,” he said in an email. “India today is passing through a difficult environment which [is] putting stress both on fundamental rights and the institutional capacity through courts to protect them. In such a situation, internet shutdowns are becoming more common.”

MAINTAINING PEACE?

Whether the government crackdown on VPNs is having its intended effect of maintaining the peace, though, remains in question.

In a 2014 paper on censorship and surveillance in Kashmir, Chitralekha Zutshi, a professor of history at the College of William and Mary in the United States who specialises in Kashmir issues, observed that the government’s position that surveillance and censorship are justified “overlooks or denies the simple fact that there is no peace in Kashmir to be maintained”.

Censorship as a counter-insurgency strategy is futile, Zutshi said, since it “virtually imprisons and destroys the lives of millions of young people”.

In Kashmir, the Indian government is always watching8 Sep 2019

The strategy is “entirely counterproductive to the alleged purposes of censorship – maintenance of law and order,” she wrote, and “it fails, in fact foils, the state objective or national dream of ‘integrating’ Kashmir with India, as it distances Kashmiris even further from the outside chance at ‘growing’ an Indian citizenship.”

And one security official in the region noted that although most bans in Kashmir are symbolic in nature and sometimes short-lived, the most recent one on VPNs has had a more tangible effect – becoming emblematic of the people’s resistance to Indian rule.

“Like a virtual insurgency in the digital world,” he said.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published