by Rishiraj Sen 8 February 2023

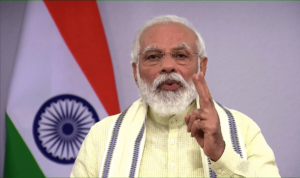

The rise of Narendra Modi in India has been attributed to multiple factors like the corruption under the Congress government, the broken nature of the state, and the gap between the ‘people’ and the ‘elites’. However, one crucial factor that has contributed massively to his success and yet has been under-spoken compared to others is the mastery of the art of advertising that his campaigns have displayed. The clear and concise slogans penetrated India, creating a powerful perception of the ‘Modi’ phenomenon.

In 2014, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) worked with stalwarts of Indian advertising and cinema like Prasoon Joshi, Piyush Pandey and Sushil Goswami to create a multidimensional electoral campaign that resonated with the pulse of the public. As Modi went to rallies, attacking the Congress for its dynasty politics and corruption in his speeches, the slogans created an alternative world where people interacted with the slogans in a dialogue format, often adding the premise to the punchline.

Slogans are ‘social symbols’ (Denton Jr 1980) which suggest ‘action, loyalty or which causes people to decide upon and to fight for the realisation of some principle or decisive issue’ (Shankel 1941). Hugh Duncan (1968) emphasises the quality of ambiguity that symbols and how it helps form new meanings while considering the fixed meanings.

BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won 336 seats in Lok Sabha in the 2014 elections. Their slogans had a repetitive quality that made the mass casually reproduce them orally or on social media. The slogan ’abki baar, Modi sarkar’ (Modi government is coming next time) was often used as the punchline to a premise that more often than not pointed towards the failure of the Congress-governed state of India. Some of the famous examples of it are ‘bohut hui mehengai ki maar/ abki baar, Modi sarkar’ (Enough with the sticks of inflation/ Modi government is coming next time) and ‘bahut hua kisaano pe atyachar, abki baar Modi sarkar’ (Enough with the oppression of the farmers/ Modi government is coming next time). This form of slogan served two purposes- first, it formed an argument where it showed the problem followed by the offered solution, which was to elect Modi as the prime minister; and second, it gave the freedom to the people to create their premises and be an active part of the campaign. This direct approach to providing simple solutions to complex structural problems helped them connect with the mass in a manner where the mass did not only have problems but a feasible, doable solution.

‘Congress-mukt Bharat’ (Congress-free India) was the slogan that was used as the mission statement for the entire campaign. The purpose of the election was to overthrow the tyrannical, dynasty-based Congress party and to set up a people’s government. The election followed a set of scams and corruption charges against ministers, including the Commonwealth Games scam and 2G Scam, and the 2011 Anti-Corruption Movement led by Anna Hazare that generated mass sentiments against the corrupt government of the Congress party. BJP tactically aligned itself with the movement and hijacked the anti-corruption agenda. While doing so, they strategically made Congress synonymous with corruption in their rhetoric. So, the idea of ‘Congress-free India’ had the undertone of ‘Corruption Free India’ for a percentage of the population who were part of the anti-corruption struggle at various levels.

The most famous of the slogans that were used in that campaign was ‘Acche din aane wale hai’ (good days are about to come). It was aspirational as well as abstract. Not only did it have a positive tone, the abstract nature of it helped people imagine it the way they want to. For X, ‘good days’ can be a corruption-free India, whereas, for Y, it can be a ‘Hindu’ India. It helped Modi to appeal to different shades of the Indian population who have different priorities. Thus, new meanings were formed alongside the fixed meanings. Furthermore, the slogan ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’ (Everyone’s support, everyone’s development) pierced through class-caste-gender dynamics as it, in its abstraction, homogenised an otherwise heterogeneous India. The abstraction worked well in opposition to the perception of the Congress party- an exclusive club of elites ruled by a family.

While most of his slogans were generic, one slogan became particularly popular because of its unapologetically Hindutva style of rhetoric. The slogan ‘jan jan modi, ghar ghar modi’ (Everyone is Modi, in every house there is Modi) was inspired by the classical, Hindu religious slogan of ‘Har Har Mahadeva’ and in some parts of India, soon took the shape of ‘har har Modi’. It portrayed Modi as an incarceration or a direct disciple of the Hindu God Shiva, which worked exceptionally well with a set of Hindu voters. The idea of Modi as the ‘Hindu Saviour’ post the Gujarat Riots of 2002 helped this slogan to gain legitimacy among its supporters.

To conclude, the campaign was designed to create and carry forward three perceptions of the brand ‘Modi’. First, it portrayed Modi as the ‘honest’ alternative to the corrupt Congress party. Second, it portrayed Modi as the people’s leader, whereas Congress was targeted for being elitist. Third, it continued the perception of Modi as the ‘Hindu Saviour’ who would act on behalf of the Hindus. This image was rather powerful to a section of the population as they always felt that Congress was the government of the minority. A feeling of betrayal was injected into the population through various slogans. Structurally, the slogans were easy to understand, had a strong sense of rhyming, and had a positive tone in most cases, which made them accessible to the common public.