Narendra Modi and his supporters took firm command over issues that dominated India’s 2019 election campaign, focusing on Pakistan as major challenge. Yet severe economic problems unaddressed before the election will dog the government. “The diversionary tactics may have been successful, but Modi’s resounding electoral victory now heightens expectations of economic success,” explains journalist Kunal Bose. “Such are his oratorical skills to mesmerize the thousands of people who assembled for election rallies across the nation that Congress President Rahul Gandhi’s repeated charge about thriving cronyism during Modi’s five-year rule didn’t find traction.” Bose describes Modi as an autodidact, self-taught, superb at debate and theater with otherwise average skills. To invigorate the economy, Modi’s team pursues foreign direct investment, lifting limits and encouraging partnerships even as protectionism surges globally. Bureaucracy, corruption, rural poverty and restless youth desperate for jobs remain big challenges for India. – YaleGlobal

Teflon Modi Eyes FDI

The prime minister, winning reelection despite India’s lingering poverty and bureaucracy, counts on foreign direct investment for relief Kunal BoseThursday, May 30, 2019

KOLKATA: As India’s elections approached, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government beat war drums against Pakistan and avoided discussion of his dismal failure in delivering on his economic promises. The strategy worked. The Modi-led Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and its National Democratic Alliance won in a landslide.

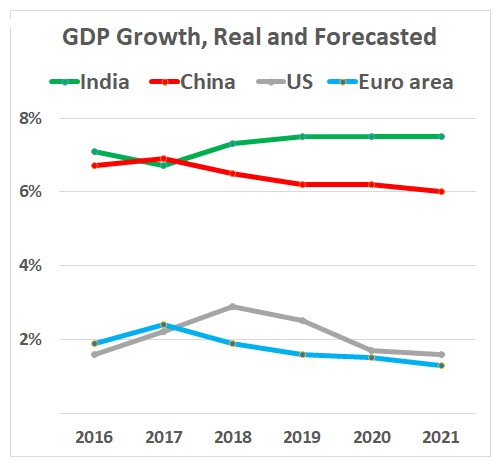

Personal attacks and communal campaigning drowned out attempts by the principal opposition party Congress to raise economic issues – its manifesto promising an income-support scheme for the poor. A Modi-chosen candidate even called Mahatma Gandhi’s assassin a “patriot.” The diversionary tactics may have been successful, but Modi’s resounding electoral victory now heightens expectations of economic success. The neglect of discussing vital economic issues was understandable since the economy continues to sputter. Officially, India’s gross domestic product in the quarter ending December 2018 grew on a year-on-year basis by 6.6 percent. Yet while among the fastest growing among the world’s major economies, India fell well below promise. Besides, the institutions associated with collection, analysis and dissemination of national data are suspect, and the statistics remain questionable. One wonders if the official GDP data faithfully reflect multi-year lows in growth in power generation, air traffic and passenger vehicle sales. Industrial output was down 0.1 percent in March, hitting a 21-month low, and unemployment is rising.

During the 2014 election campaign, Modi, then a successful chief minister of Gujrat, promised creation of at least 10 million jobs a year. But, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, the unemployment rate at 8.1 percent in April 2019 was the highest in the last two and a half years. Notwithstanding Modi’s promise to double farmers’ income by 2022, rural distress is widespread.

Modi, an autodidact, steered clear of uncomfortable facts and focused on his success in fighting terrorism from across the border, especially the unprecedented response to Pakistan-backed terrorism with an airstrike inside Pakistan. He also claimed credit for raising India’ profile abroad and fighting corruption and cronyism. Such are his oratorical skills to mesmerize the thousands of people who assembled for election rallies across the nation that Congress President Rahul Gandhi’s repeated charge about thriving cronyism during Modi’s five-year rule didn’t find traction.

Gandhi wrongly assumed that he could damage Modi’s clean image by raising the issue of the Anil Ambani group, with no defense experience, receiving a major offset contract in New Delhi’s Rafale aircraft deal with Dassault of France. In the past, many politicians and bureaucrats fell from grace because of attempts to make money in defense deals. But Modi’s superior campaigning and his supporters’ widespread use of fake news and internet trolling turned him into a Teflon candidate.

The defense industry has turned out to be a principal tool to bring modern industry to India. An underdeveloped defense industry has made India nearly 60 percent dependent on imports. Realizing that the only way to make the sector world class is to create conditions for large inflows of foreign direct investment and technology, the National Democratic Alliance government raised FDI limits to 49 percent from 26 percent. Furthermore, the government will favorably consider 100 percent FDI for sophisticated technology transfers. Defense is no longer the exclusive domain of public-sector undertakings.

.png)

Private groups such as Tata, Mukesh Ambani–led Reliance and Mahindra & Mahindra have entered into partnerships with leading foreign defense equipment companies to manufacture locally. From Lockheed to Dassault to Boeing, every foreign defense firm wants a slice of India’s booming market. Under Modi’s Make in India program, the government has mandated that imported defense products should include at least 30 percent Indian-made parts. The environment is congenial for India’s local defense industry to come of age, but with foreign funding and technology.

Foreign institutional investors played a key role in the Indian stock market, and their growing strength has triggered reforms, bringing market practices in line with global norms. The National Democratic Alliance’s impressive victory with BJP alone commanding a comfortable majority has made institutional investors hopeful that Modi will not wait long to remove key hurdles to acceleration of India’s growth and add robustness to the market.

Mark Mobius, partner of Mobius Capital, says the “resounding” victory is a welcome development for the market, but foreign investors already have positive feelings about India, describing the country as “really the winner” among emerging markets. “Of course, with China down embroiled in a trade war with the US, India is looking very, very good,” he said. Other institutional investors have voiced similar sentiments. “I expect India to outperform other emerging markets because it is not that much affected by the trade war,” Hertta Alava of Nordea told ETMarkets, adding that “Modi in his second term has a free hand to carry out reforms.”

The range and quality of reforms will depend on the input Modi receives from his advisers. At least two leading commentators – Lionel Barber, Financial Times editor, and Ruchir Sharma, Morgan Stanley’s head of emerging markets – have expressed doubt as to whether Modi gets proper guidance on economic issues from the few close to him. Barber writes, “it is uncertain whether he grasps the economy’s complex challenges, or the financial system’s woes. Nor is it clear that his few advisers have the technical expertise – or courage – to explain it, to help him calibrate his kinetic policymaking.” Sharma is equally emphatic that the prime minister needs “new voices into his brain trust… more expertise in his inner circle might have helped prevent an experiment like demonetisation.” Modi would do well to heed Sharma’s warning that the voters will not be forgiving if he makes another mistake like demonetization.

The biggest challenge for the government will be to create employment opportunities for millions of youth who join the job market every year. On becoming prime minister in 2014, Modi made it a priority to seek FDI in every area of the economy from software and IT to automobiles and retail with hopes of creating quality jobs that fulfill the aspirations of an urbanizing and modernizing nation for making products for the world market.

The Indian automobile industry is the best example of how none of the major global brands wants to miss out on this market’s promise. The latest to jump on India’s auto bandwagon is Morris Garages owned by China’s largest automaker SAIC. At its Halol plant in Gujarat, MG will make cars with 75 percent localization, creating a lot of jobs. Similarly, Scandinavian furniture-maker Ikea, which made its debut in India in August 2018, is committed to procure at least 35 percent of what is kept in its stores. Wal-Mart of the US completed a $16 billion acquisition of India’s largest e-commerce firm Flipkart in August in the hope that the two would achieve more together than either could separately.

Unfortunately, FDI is still not significant in metals and mining despite the sector’s pressing need for foreign capital and technology. This is because at every stage of mining, from exploration to prospecting and securing leases, investors encounter frustratingly long bureaucratic delays. A case in point is the world’s largest producer of steel ArcelorMittal, which has been waiting to conclude its acquisition of insolvent Essar Steel. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code requires resolution of such deals within nine months, but more than two years later, ArcelorMittal still does not own Essar Steel. Simpler rules would make India a hot destination for FDI.

Modi’s massive electoral victory highlights the domestic challenges of unemployment, bureaucracy and corruption awaiting the new government.

A former correspondent for Financial Times in India, Kunal Bose now writes for Euro Money publications and Business Standard.

The article was published in Yaleglobal online on 29 May 2019

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published