Legal documents can send a diplomatic message. But

the questions raised might lead to unexpected turns.

The US Department of Justice has unsealed an indictment alleging a plot directed from India to kill an American citizen on US soil. The broad accusation about targeting Sikh separatists had already been aired in media reports, but the grisly new details from the grand jury indictment are unsettling – not least the claim that an official in India, a democracy, heavily courted by Western partners, would be entangled in “murder-for-hire” inside the United States.

“We have so many targets,” one of the accused was recorded boasting, according to the 15-page court document, listing hits planned in New York, California, and Canada. The indictment also sheds new light on Canada’s earlier but unspecified “credible allegations” that agents of the Indian government had been involved in the killing in June of a Canadian in Vancouver.

These grand jury indictments never offer the full outline of the government’s case. Much of the evidence is saved for the trial. The public detail so far also leaves enough room – should the allegations be proven – for India to demonstrate that this was not a sanctioned operation. And the White House may accept an explanation blaming rogue agents, provided that New Delhi shows it takes the matter seriously, which was not the case following Canada’s initial claims.

Managing the diplomatic fallout will be complicated. These US Department of Justice documents can carry consequences that spin off in unexpected directions far beyond the specific legal case, something I observed first-hand working as a journalist. In 2017, I helped break the story about China’s influence campaign in Australia. Much of the early detail came from US charges revealed two years earlier in a New York court against a woman who also happened to be deeply intertwined with Australian political and business leaders. The extent of China’s influence campaign in Australia would have been far more difficult to demonstrate without those documents. The charges became something of a crib sheet, as reporters attempted to fill in the gaps.

This same process is already evident in the India case. Reporters are using the indictment to probe sources for more information. What detail the US indictment does provide helps shape the right kind of questions they ask and refute attempts to brush off the charges.

The same day the indictment was made public, media reports also revealed that CIA Director William Burns had flown to New Delhi in August to front local counterparts about the case, followed by Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines in October. The indictment alleged that in May and June “an identified Indian government employee”, claiming to be a “senior field officer” in “intelligence” and “security management”, directed a plot to kill a supporter of a Sikh separatist movement in New York. Media have named the target as activist and lawyer Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, who is wanted in India.

Media reports noted India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Washington in June, coinciding with the conspirators suddenly warning, as revealed in the indictment, that “the murder should not occur during anticipated high-level diplomatic engagements between India and the United States” otherwise “political things” could result.

Reporters also discovered that US President Joe Biden had subsequently privately raised the case with Modi during the G20 summit in September. And US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan was reported to have demanded the Indian government investigate and hold to account those responsible – “and that the United States needed an assurance that this would not happen again”.

Indian media has since quoted sources claiming that FBI Director Christopher Wray will be in India next week to canvass the case. The continued high-level attention sends a message of seriousness. If the United States assessed this was merely a criminal matter, the principals of the administration would not be so engaged.

It is tempting to see a deeper diplomatic tactic in the use of such legal documents. In 2010, the US Department of Justice unsealed affidavits from an FBI investigation into Russian sleeper agents. The shock of the revelations was initially treated with near incredulity – “isn’t the Cold War long over?” Media commentators laughed that these Russians didn’t even seem to be very good spies, having cultivated academics and think-tankers rather than hunting secrets. But as the detail emerged and realisation dawned about the scale of Russian influence operations in the United States, the Obama era effort to “reset” relations with Moscow was abandoned.

In the India case, extra details are slowly coming to light.

Local journalists in India reported that the one accused named in the indictment, Indian citizen Nikhil Gupta, was handed to US authorities last month in Prague, where he had been held by Czech authorities at America’s request since June. This extra international dimension to the case adds new intrigue. Gupta was described in the indictment as claiming to be involved in the illicit drugs and weapons trade. He was exposed by contacting a confidential source of the US Drug Enforcement Administration in a bid to arrange a hitman. An undercover US law enforcement officer then posed as a hitman to further the investigation.

But most interest swirls around the identity of the person in India said to have directed the plot, known only as “CC-1”. The indictment reads, “CC-1 was employed at all times relevant to this indictment by the Indian government, resides in India, and directed the assassination plot from India.” Reporters are speculating about what position this might be, pointing to the earlier expulsion from Canada of an officer from India’s external spy agency, Research and Analysis Wing. The Hindu newspaper asked whether the Modi government had “been less than honest about what it knows”, given the outrage expressed following Canada’s claims while privately knowing the US investigation was afoot. The Washington Post declared “a red line” had been crossed: “Any foot-dragging or coverup will weigh upon all the other worthy efforts to build a strategic partnership.”

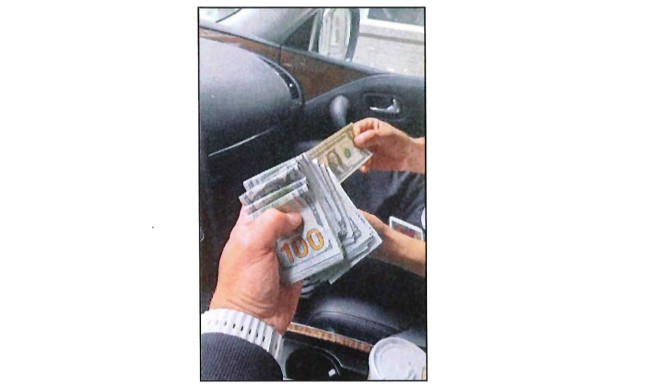

Clearly, a network was involved. The indictment refers to “CC-1, working together with others in India and elsewhere.” The court document includes a surveillance photo of a US$15,000 cash handover, said to have been arranged from India, as a down-payment on the killing against the final price of US$100,000. The detail provided also hints at a further operative, or sophisticated monitoring at least, within the United States beyond the individual recruited to coordinate the hit. “CC-1” was able to furnish details about the target’s address, telephone numbers and email – and also when he was at home.

India, for its part, has referred obliquely to a “nexus between organised criminals, gun runners, terrorists and others”. New Delhi has now said that a “high-level enquiry committee” was constituted on 18 November to examine the matter. That came two months after Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau first levelled the accusation about the killing of Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Vancouver. India has blamed Canada for not sharing information – which if true, might be a consequence of the originator control rules for the sharing of intelligence within the Five Eyes grouping. Or maybe, as one local Indian columnist notes, there simply isn’t much trust in India.

Either way, the overlap between the cases evident in the US indictment puts the concern to rest. Just hours after masked gunmen killed Nijjar in Canada, “CC-1” allegedly had access to a video of the “bloody body slumped in his vehicle” and sent it to his co-conspirators in the United States to urge them on. Trudeau has pointed to the release of the indictment, saying, “the news coming out of the United States further underscores what we’ve been talking about from the very beginning, which is that India needs to take this seriously.”

The US Deputy National Security Adviser Jonathan Finer visited India last week, with the White House releasing a statement acknowledging India’s investigation “and the importance of holding accountable anyone found responsible”. Had the plot in America not been disrupted, it’s doubtful whether Finer would have left the impression with Indian media that the mature ties between the countries will allow differences to be resolved. Even so, as a commentator noted, “the rhetoric of ‘shared values’ may be a casualty”.