by Vasu Aggarwal 16 September 2020

I. Introduction

The meaning of “Hindu”, in general, has remained ambiguous. While the inception of the term was with a geographical connotation, it took a religious connotation with time. The connotation further seems to be changing with political actors trying to define it for political purposes. Similarly, the legal definition “Hindu” remains uncertain.

The reason for this uncertainty is the lack of any proper definition in the statutes. Though the judiciary has defined it in a broad sense to have particular features, this definition cannot be applicable across different statutes in which we come across the term “Hindu”.

“Hindu” has been loosely used in different statutes especially the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955. “Hindu” seems to be used in two contexts in the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955. First, in the long title and short title which is in terms of applicability of the Act, and second, in section 2 – Hindu by Religion- which is in a religious sense. This ambiguity in the meaning of the term “Hindu” can open up a Pandora’s box. Thus, there is a need for clarity on the same. Therefore, with the help of this paper, I seek to establish: first, that the usage of the term “Hindu” in long title, as well as short title of the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955 (‘the Act’), is a misnomer, and therefore, it would be redundant to define it; second, that the term “Hindu by Religion” (‘Hindu (R)’) in section 2 of the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955 should be defined in terms of conversion, and reconversion for the purpose of the Act based on the outcome of the case it concerns.

The scope of this paper has been restricted to the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955. A distinction has been drawn between the term “Hindu” which has been used in the long title, in terms of the applicability of the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955, and the term “Hindu (R)” in section 2 of the Hindu Marriages Act, 1955 which has been used in religious sense. However, “Hindu” has been loosely used in the first part of this paper to understand the meaning of the term.

II. Hindu’: A Misnomer

A. Reading Section 2 in Consonance with Long Title and Short Title

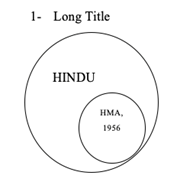

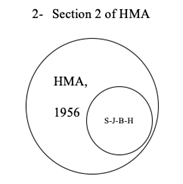

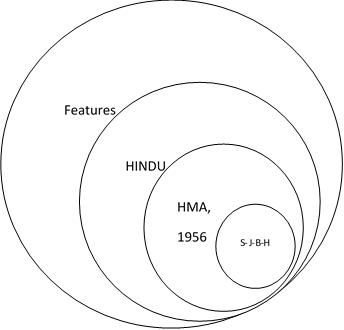

Section 2 of the Act makes it applicable to those who are “Hindu (R)”, in any of its forms or development. Furthermore, it is also applicable to Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists, and whoever who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi, or Jew by religion, unless it is proved that the person is not governed by “Hindu” law but customary law.[ii] [represented in Diagram 2] The long title of the Act reads, ‘An Act to amend and codify the law relating to marriage among Hindus’.[iii] [represented in Diagram 1]

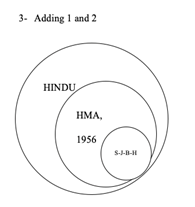

The long title clarifies the intention of the legislation to apply the Act to the Hindus, and section 2 makes it applicable to the Hindus (R), Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, and others. This implies that “Hindus (R)”, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, and others would fall under the definition of “Hindu”. There is no express definition of the term “Hindu” either. Therefore, it prima facie appears that the definition of “Hindu” was intended to be broad and include everyone other than Muslims, Christians, Parsis or Jews by religion. [represented in Diagram 3]

B. Judicial Decisions

To test the veracity of the above implication, it becomes pertinent to look at judicial decisions that have defined the term “Hindu”. The term “Hindu” has not been interpreted by the court in the context of the Act. In addition to this, “Hindu” has not been defined across different legislations in India. However, it has been interpreted by the judiciary for the purpose of other legislations. Following rules of statutory interpretation, to understand the meaning of the term “Hindu”, we look at the judicial decisions which define the term “Hindu” in different contexts.

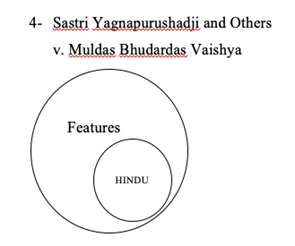

The courts have, in multiple decisions, concerning a similar question of law, where the outcome was dependent on the meaning of the term ‘Hindu’ looked at the meaning of the term.[iv] The courts looked at the historical genesis of it which has given rise to controversies, however, it is widely accepted that it arose as a term used by Persians to describe those who lived near the river Sindh as “Hindus”.[v] With time the development of this term has taken religious connotation.[vi] Though it has been accepted that “Hindu” as a religion does not have any fixed dogmas or tenets that each “Hindu” has to follow, the courts have been able to lay down broad features to understand what a “Hindu” institution is.[vii] These broad features include acceptance of Vedas in the highest authority of philosophic and religious matters, acceptance of the view of the great world rhythm, among others.[viii] For theoretical purposes, these broad features should be generally followed by those ascribing to these “Hindu” institutions. Therefore, the consequence of it is that a “Hindu” should accept Vedas in the highest authority of philosophic and religious matters, accept the view of the great world rhythm, among others. [Reference- Diagram 4 in Appendix]

We had established that Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists fall under the definition of “Hindu” by looking at s. 2 of the Act read with the long title, and since “Hindus” should accept of Vedas, accept views of great world rhythm among others. Therefore, Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists should accept Vedas, accept the view of the great world rhythm, among others. [represented in Diagram 5]

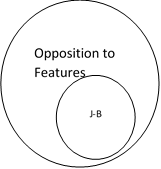

However, to test the above conclusion, it becomes important to go into whether Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists actually accept Vedas, etc. Sramana religions arose in specific opposition to Vedic teachings.[ix] These Sramana religions include Buddhists and Jains.[x] Therefore, Jainism and Buddhism arose in strict opposition to the Vedic teachings. [represented in Diagram 6]

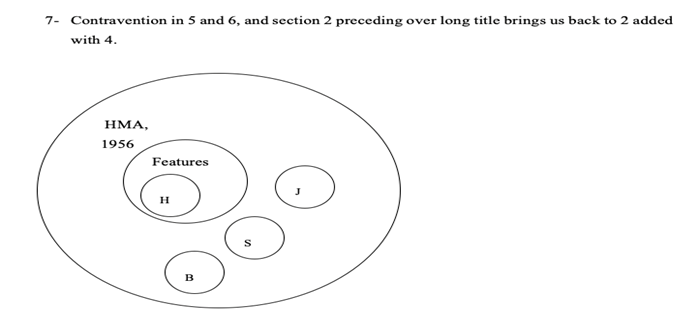

The two conclusions – Jains, Buddhists should acceptance Vedas, and Jainism, Buddhism arose in opposition to Vedic teachings- are in contravention to each other.

C. Resolving the Contravention in Section 2 and Long Title

This conclusion is drawn when implication that Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists fall under the definition of “Hindu” is taken from harmonious reading of s. 2 and long title of the Act. Since this is an absurd conclusion, therefore, they both have to be read separately. When both these sections are read separately there is a contravention in the reading about whether Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists should fall under the definition of “Hindu”. According to the rules of statutory interpretation, substantive provisions take precedence over the long title.[xi] Therefore, s. 2 prevails over the long title. Thus, at this stage, it has to be established that the usage of term “Hindu” in the long title of the Act is incorrect. S.2 makes the Act applicable to “Hindu (R)”. Since the predicament regarding “Hindu” and “Hindu (R)” has been resolved because “Hindu” has been used incorrectly and thus, must not be considered, an attempt is made to look at the definition of “Hindu (R)” in the next part of the paper. [Represented in Diagram 7 in Appendix]

III. Definition of ‘Hindu (R)’ for the purpose of the Act.

In the previous part, “Hindu (R)” has been theoretically concluded to be someone who accepts Vedas, accepts the view of the great rhythm among others. This conclusion was drawn from looking at the definition of the “Hindu” institution laid down by the courts. I demonstrate, in this chapter, that for practical purposes this definition of “Hindu” cannot be extrapolated to be applied to a “Hindu (R)” personal for the purpose of the Act.

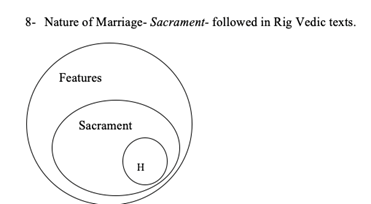

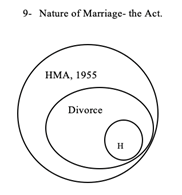

A. Nature of Hindu Marriage in the Act in Contravention with Rig Veda/Manu Smriti

The nature of Hindu marriage that was followed during Rig Vedic times was a sacrament.[xii] It has been defined as being sacrament by the Manu Smriti. It reads that men and women may not be disunited when they’re married.[xiii] [Reference- Diagram 8 in Appendix] This means that divorce is antithetical to this nature of marriage. However, the Act provides for dissolution- read: disunity- of the man and woman.[xiv] [Reference- Diagram 9 in Appendix] Therefore, the Act provides for the nature of marriage to be antithetical to Vedas.

It is conceded that there exist opinions to the contrary that while the Act may provide for provisions to disunite, this wouldn’t mean that religious union would be dissolved.[xv] However, since the woman and man are legally and practically disunited, it is essentially opposite to the nature of marriage defined in Manu Smriti. [Diagram 8 and 9 are in contravention]

Therefore, since the way the courts have defined “Hindu” in the context of institutions doesn’t fall in line with the Act, “Hindu (R)” cannot be defined in terms of acceptance of Vedas, or acceptance of the view of the great world rhythm for purposes of the Act.

B. Significance of Defining “Hindu” for Conversion and Reconversion

Since we are trying to define “Hindu (R)” for practical purposes now, it is relevant to bring out the significance of defining it. The significance of it, in terms of defining it, is only for the purpose of converts and re-converts.[xvi] This is because the Act would be applicable to anyone who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jew by religion, or others.[xvii] Therefore, in terms of applicability of the Act, we have clarity on whom the Act is not applicable to, and therefore, whom the Act is applicable to.

It is significant to look at the definition of ‘Hindu (R)’ in the context of conversion and re-conversion because a situation may arise when the marriage may not be considered to be solemnized if the conversation or reconversion didn’t take place.[xviii] If the marriage is not considered to be solemnized, the children of this couple become illegitimate, and the spouse would lose the right to maintenance. A similar question of law- regarding converts and reconverts to “Hindus”- has been interpreted by the courts in different cases. While in one case, bona fide intention of the person converting was defined to be the criterion for deciding it,[xix] in another case, it was held that there are two elements -there has to be converted, and acceptance in the community- for a valid conversion.[xx] This question has also been looked at by the law commission, and elaborate recommendations in relation to a valid declaration have been laid down.[xxi] It is believed that the definition, in terms of conversion and reconversion, should take into consideration the outcome thereof.

C. Two Possibilities: Mutual and Non-Mutual

There are two possibilities when the question of conversion and reconversion comes up to the court. First, when there is a mutual want for divorce. In that case, there is no one who is made worse off due to this declaration. When there is no one who is made worse off as there is a mutual want of divorce, and someone is made better that is children of the couple and the spouse who could receive maintenance, there is a Pareto optimum outcome. Judicial decisions must be in favor of Pareto optimum outcome because there is no aggrieved party.[xxii] Therefore, the convert must be considered legitimate for the purpose of the Act. In this case, the question of conversion becomes irrelevant.

Second, if one spouse alleges the marriage to not be solemnized on grounds that the conversion was invalid, it would become relevant to define “Hindu” in terms of conversion and reconversion. However, these conditions are from a singular perspective that is from the one who converted. Conversion and reconversion should not be seen in isolation from the spouse alleging the marriage to not be solemnized. This is because there is a possibility that the spouse alleging the conversion to be invalid might be doing it with a mala-fide intention. This is because at the time of marriage, the spouse would have known that the conversion to be invalid and that marriage couldn’t have been solemnized. Despite that, the spouse married knowing that, the reason for the claim could be to deprive the other spouse of maintenance rights. A just outcome, therefore, would be to provide the spouse maintenance rights in those cases, and therefore, construe the spouse to be converted.

Thus, while laying down the pre-conditions for conversion or reconversion, apart from looking at acceptance in the community of the person converted, or intention of the convert, it is important to look at the outcome. This is also facilitated by the fact that the meaning of “Hindu” has not taken a strict meaning, and has been evolving through the course of history as discussed earlier. Therefore, when courts have the discretion to define it, it should do it keeping in mind the justness of the outcome.

IV. Conclusion

The problem identified was that the definition of “Hindu” is uncertain in legal terms, especially in terms of the Act. With the help of this paper, I have proved how “Hindu” used in the long and short title of the Act is a misnomer. This has been done by showing that long title is in contravention with a substantive provision, section 2, of the Act. Therefore, it should not be read as “Hindu”.

After establishing that “Hindu” in terms of the long title is a misnomer, the definition of “Hindu (R)” that is used in s. 2 of the Act is defined. For practical purposes, it is said that the definition of this term is only relevant in terms of conversion and reconversion as this Act is applicable to non- “Hindu (R)” as well. This is because, in the absence of valid conversion, one of the spouses may lose maintenance rights.

In that situation, there are two possibilities. First, when there is mutual consent to the divorce, there should not be any such requirement for elements of conversion because the marriage must be considered valid because there is Pareto optimum outcome. Second, when it is not mutual, the outcome of the decision thereof should be considered. This is facilitated by an absence of strict definition. Therefore, apart from looking at acceptance in the community of the person converted, or intention of the convert, it is important to look at the outcome which should be just and fair.

[ii] Hindu Marriages Act, 1955, s 2.

[iii] Ibid long title.

[iv] Sastri Yagnapurushadji And Others V. Muldas Bhudardas Vaishya And Another 1966 AIR SC 1119; Dr. Ramesh Yeshwant Prabhoo V. Prabhakar Kashinath Kunte And Others 1996 AIR SC 1113; Bramchari Sidheswar Shai And Others V. State Of W.B And Others 1995 SCC 4 646.

[v] Lloyd Ridgeon, Major World Religions (RoutledgeCurzon, 2003) 10; Gavin D. Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism (Cambridge University Press 2018) 6; Brian K. Pennington, Was Hinduism Invented: Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction of Religion (Oxford University Press, USA 2005) 77.

[vi] Sastri Yagnapurushadji and Others V. Muldas Bhudardas Vaishya and Another 1966 AIR SC 1119.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Sastri Yagnapurushadji And Others V. Muldas Bhudardas Vaishya And Another 1966 AIR SC 1119; Dr. Ramesh Yeshwant Prabhoo V. Prabhakar Kashinath Kunte And Others 1996 AIR SC 1113; Bramchari Sidheswar Shai And Others V. State Of W.B And Others 1995 SCC 4 646.

[ix] Patrick Olivelle, The Āśrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution (Oxford University Press, 1993) 11-12.

[x] AL Basham, History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas – a Vanished Indian Religion (Motilal Banarsidass, 1981) 95.

[xi] Macquarie Bank Limited v. Shilpi Cable Technologies Ltd 2017 SCC ONLINE SC 1493.

[xii] Paras Diwan, Modern Hindu Law. Allahabad (Allahabad Law Agency, 2008).

[xiii] Manu Smrit (DigitalLibraryIndia) <https://archive.org/details/ManuSmriti_201601/page/n12> accessed 21 November 2019.

[xiv] Hindu Marriages Act, 1955, s 13.

[xv] B.N. Sampath, “Hindu Marriage As A Samskara: A Resolvable Conundrum.” (1991) 33 (3) Journal of the Indian Law Institute 319.

[xvi] Betsy and Sadanadan Vs Nil 2010 ILR KER 1 46.

[xvii] Hindu Marriages Act, 1955, s 2.

[xviii] Hindu Marriages Act, 1955, s 5.

[xix] Betsy and Sadanadan Vs Nil 2010 ILR KER 1 46; Sapna Jacob, Minor vs The State of Kerala & Ors AIR 1993 Kerala 75.

[xx] M.Chandra vs. M. Thangamuthu (2010) 9 SCC 712.

[xxi] Law Commission, Government Of India Conversion/Reconversion To Another Religion – Mode Of Proof Conversion/Reconversion To Another Religion – Mode Of Proof (Law Com No 234, 2010) para 15.

[xxii] Andrew Altman, Arguing About Law (first published 1996, Wadsworth Publishing Company 2000); United States Fidelity & Guaranty Company v. Jadranska Slobodna Plovidba 683 F.2d 1022.