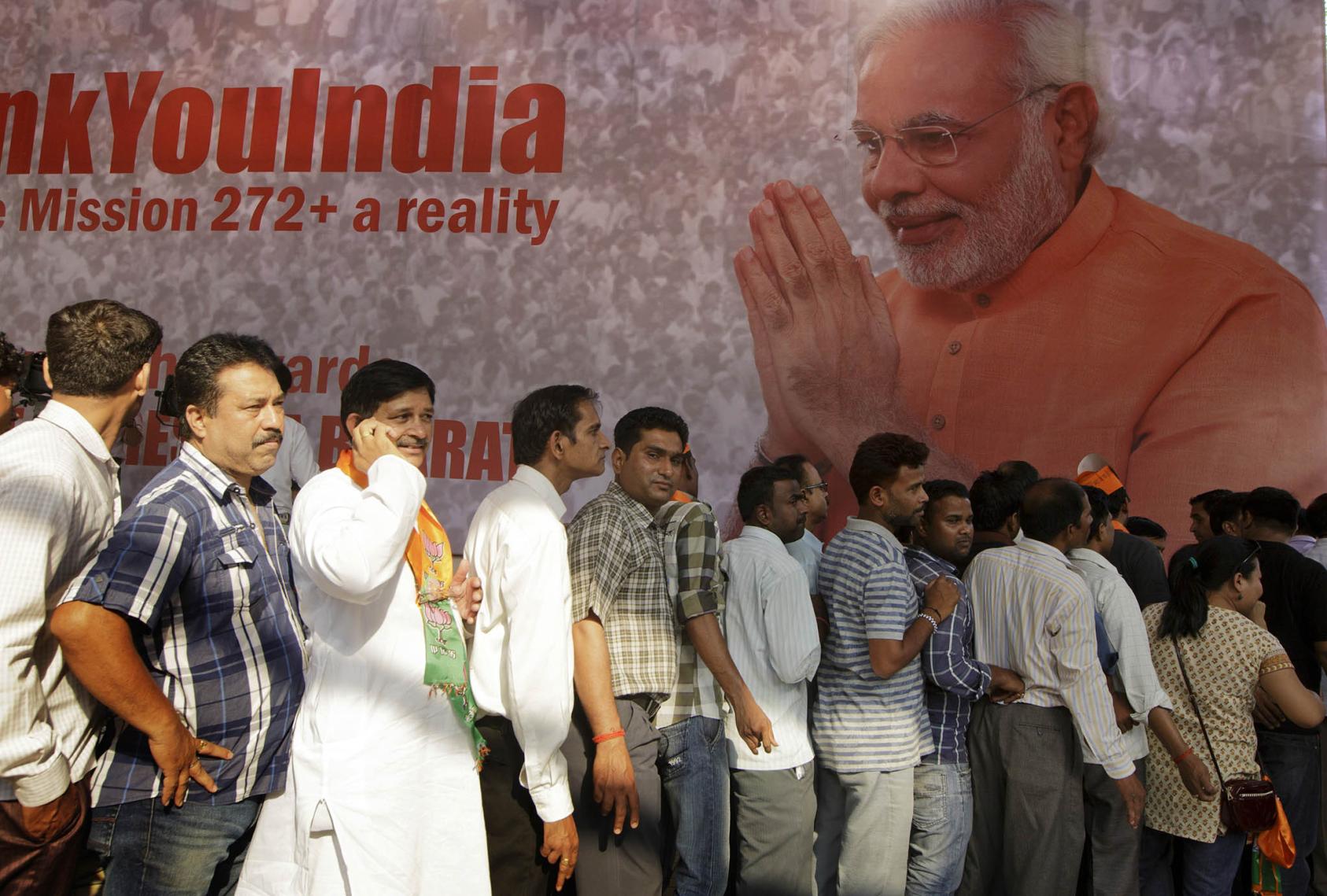

Historically, foreign policy has rarely been a core area for political debate in India’s national elections. This year, the BJP is again widely anticipated to win a parliamentary majority, however, as hundreds of millions of Indian voters head to the polls, both Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition INDIA alliance, headed by the Congress Party’s Rahul Gandhi, have made a point to highlight their differences on several high-profile national security issues.

Pakistan: India’s Enduring Foe

Salikuddin: General election season in India often opens the door to bluster about Pakistan that plays well domestically but does not necessarily reflect the policy reality in New Delhi. The most recent dust-up in India surrounds the resurfacing of comments by veteran Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar, where he described Pakistanis as the “biggest asset of India” and recommended resuming dialogue with Pakistan. His comments, many of which were taken out of context, also seem to recommend engaging with Pakistan due to fear of its nuclear arsenal.

These were followed by public comments by Srinagar member of Parliament Farooq Abdullah of the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, a party within the opposition INDIA alliance, warning that taking back Pakistan-administered Kashmir (a policy outlined in the BJP manifesto) would not be easy because Pakistan was a nuclear-armed state and they were “not wearing bangles.” (“Wearing bangles” is a common Indian saying used to indicate weakness.)

Modi called out both Aiyar and Abdullah in a campaign speech, characterizing the opposition as soft on Pakistan and asserting that a renewed BJP-mandate would ensure that India would be tough on Pakistan and make the cash-strapped country “wear bangles.” The comments were intended to portray Modi as tough on India’s adversarial neighbor and played well to BJP’s political base.

At recent election rallies, BJP leaders Amit Shah, the home minister, and Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath doubled down on these claims, emphasizing that a re-elected BJP government would take the additional step of “taking back” Pakistan-administered Kashmir, thereby fulfilling a long-standing pledge in the BJP manifesto to reclaim the part of historic Kashmir that lies on the Pakistani side of the Line of Control (LOC). The decades-long status quo dividing India and Pakistan at the LOC would appear to make this claim impractical. That said, the BJP and Modi have a history of fulfilling their manifesto pledges, including the 2019 revocation of Kashmir’s autonomous status.

While political barbs on Pakistan play well during elections, the reality is the statements often have little to do with the BJP’s or Congress’s policies on Pakistan. Both Aiyar and Abdullah don’t reflect the Congress consensus, and the party spokesperson distanced Congress from Aiyar’s remarks. In fact, both BJP’s and Congress’ manifestos call out Pakistan for supporting cross-border terrorism.

The ground reality is that the BJP and Modi have used their decade in power to change the terms of conversation with Pakistan. That effort started with an outreach to Pakistan when Modi received then-Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in New Delhi in 2014 and made a surprise visit to Lahore in 2015. In 2019, India and Pakistan worked together to open the Kartarpur Sahib religious pilgrimage corridor. However, after the 2019 Pulwama-Balakot crisis and the BJP’s decision to change the constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir, relations between the nuclear-armed rivals have been at a diplomatic standstill. Even so, the two found a way to negotiate and maintain a three-year cease-fire along their disputed border. Their ongoing back-channel dialogue has also helped to prevent escalation, most notably in the case of the errant Brahmos missile launch in 2022.

Bottom line, the BJP’s often tough political rhetoric on Pakistan can score political points with the party faithful, but real policy attention in New Delhi has shifted to other threats and challenges, most notably China.

Countering Overseas Threats to India

Markey: Pursuing a muscular approach to foreign policy has long been a central theme of the BJP’s national security policy. The aim has been to draw a sharp and damning contrast with previous Congress-led governments. Modi, speaking at a campaign rally in April, proclaimed, “Whenever we had a weak and unstable government in the country, our enemies capitalized on it. Whenever we had a weak and unstable government, terrorism spread. Today, we have Modi’s strong government in India, and that is why ‘aatankwadiyon ko ghar mei ghus kar mara jata hai’ [our forces are killing terrorists on their own turf]. Today we have a strong government. India’s Tiranga [the flag] has become the guarantee of safety even in war zones.”

BJP defense minister, Rajnath Singh, pushed the rhetoric still further, threatening, “any terrorist trying to create turmoil in India won’t be spared.” He added, “If they run away to Pakistan, we will enter Pakistan to kill them.”

Although these statements were clearly made for political effect, they were not mere bluster. Over its decade in office, the BJP has taken a decidedly different approach from its immediate predecessors when it comes to managing perceived national security threats from Pakistan and beyond. Although the full contours of this policy shift may not yet have come to light, recent news reports from the Guardian, Washington Post, and Australia’s ABC suggest that India’s external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing, has expanded and intensified its overseas operations, especially against Sikh separatists, known as Khalistanis.

The shift is consistent with comments that India’s current national security advisor and close Modi confident, Ajit Doval, made shortly before he joined the BJP government in 2014. As the head of a prominent think tank at the time, he argued that India should pursue a strategy of “defensive offense,” by which he meant that India should attack its terrorist enemies outside the nation before they could strike India’s territory.

Having served nearly a decade as national security advisor, Doval has been perfectly placed to implement his preferred approach. No one could have been surprised that it would target Pakistan-based terrorists, although most would have expected the primary targets to have been anti-Indian Islamists rather than Khalistanis. Moreover, U.S. and other Western policymakers probably never anticipated that the campaign against India’s adversaries would extend to North America, Western Europe or Australia.

China: India’s Rising Rival

Lalwani: In 2014, the Modi-led BJP had high hopes for a constructive India-China bilateral relationship based on investment, trade and learning as India aspired to emulate China’s rise as an Asian juggernaut in a new multipolar world. Despite periodic foreign policy frictions and some militarized border standoffs, Modi made leader-level diplomacy the engine of the relationships, meeting with President Xi Jinping 18 times between 2014-2020. However, the relationship nosedived with the border crisis in the disputed Ladakh region that began in spring 2020 and escalated with the first deaths on the border in 50 years. Although there has been ongoing dialogue and limited disengagement from the border, the two countries maintain significant forward deployed military forces in a tense border standoff.

The opposition Congress Party has sought to make the Modi government’s handling of the China relationship a voting issue as foreign policy has become more salient among the Indian electorate. In their manifesto, Congress claims, “Chinese intrusions in Ladakh and 2020 Galwan clashes represented the biggest setbacks to Indian national security in decades.” Congress spokesman Manish Tewari has accused the Modi government of having “continuously shown a weak-kneed approach towards China ever since 2020.”

In defense of its China policy, BJP officials have contrasted it with Congress’s handling of the 1962 war. With Home Minister Shah claiming, “[Prime Minister] Nehru had said ‘bye-bye’ to Assam and Arunachal Pradesh,” whereas under the Modi-led government, “China couldn’t encroach a single inch of land.” Union Minister and former Army Chief VK Singh has added to this defense arguing, “Neither has China occupied anything nor has it been allowed to occupy anything. The situation that was there in 2012 is the same even today. There has been no change.”

Congress, for its part, has countered with claims that “China has occupied 2,000 sq km of Indian soil” and built villages in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh — citing evidence presented in the Indian Parliament by a member of parliament from Modi’s own BJP. Congress General Secretary Jairam Ramesh has further characterized the BJP’s refusal to acknowledge incursions as a lie “used by the Chinese … to deny their encroachments on Indian territory.”

It is difficult to assess the accuracy of competing assessments given the murky nature of the territorial claims and control over the disputed borders — although open source imagery analysis suggests there may be some Chinese construction in India’s state of Arunachal Pradesh and scholars of the border dispute assess that China’s incursion in the spring of 2020 has effectively blockaded areas of the Line of Actual Control previously claimed and patrolled by Indian troops that amounted to up to “2,000 square kilometers of territory.” Regardless, February 2024 survey data shows voters are generally supportive of Modi’s foreign policy going into this election and has consistently and overwhelmingly supported the Modi government’s handling of border relations with China.

Despite the public debates about past border management, from an outside perspective the Congress and the BJP’s substantive remedy to the China challenge appears quite similar going forward, even if there are stylistic differences in rhetoric. The Congress manifesto claims they will “work to restore the status quo ante on our borders with China” through “quiet attention to our borders and resolute defense preparedness.”

Over a decade ago, a group of strategic scholars close to the ruling Congress government prescribed doing this by accelerating upgrades to border infrastructure, reducing India-China asymmetry in “capabilities and deployments,” and developing “operational concepts and capabilities to deter any significant incursions from the Chinese side.”

This is not inconsistent with how the ruling government has sought to build up its strategic border defenses through new force deployments, weapons systems, and logistics infrastructure and by standing firm on its territorial claims without inflaming tensions with China. As part of its national security platform within its 2024 manifesto, the BJP has also pledged to double down and “accelerate development of robust infrastructure” along the Indo-China borders. While there are signals that if a Modi government returns to power for a third term it may seek some sort of détente with China on the border issue (to put the “abnormality” behind them), significant steps at de-escalation and de-induction of forces to a return to a pre-April 2020 status quo seems extremely unlikely in the near to medium term.

source : usip