NEW DELHI: Two leaders of Asia’s largest powers – Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi – emerged on the scene two years apart with similar promises. Different paces of growth, different approaches taken by each, dramatically altered their respective positions, giving China a strong upper hand. Global unpredictability may have encouraged Xi to a conciliatory position, giving India only a brief breathing space.

Xi assumed the powerful office of general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in November 2012. Soon afterward he became chairman of the Central Military Affairs Commission, and in March 2013 was elected president of the Republic of China. Leadership of the party, military and the state was firmly in his hands. The 19th Party Congress in November 2017 formalized his elevated status through a constitutional amendment enabling him to remain president for life. Xi Jinping Thought is enshrined in the Constitution alongside Mao Zedong Thought, placing Xi in the same category as Mao – an undisputed political and ideological leader. This consolidation of political power has coincided with a phase of assertive, even aggressive, foreign policy as China stakes a claim to international status equal to that of the United States. In Asia, China claims a pre-eminence sanctioned by a narrative of past glory and present scale of economic and military power. This has inevitably altered the context within which it relates to the world and specific countries. Terms of engagement reflecting growing power asymmetry between the two Asian giants have also impacted India-China relations.

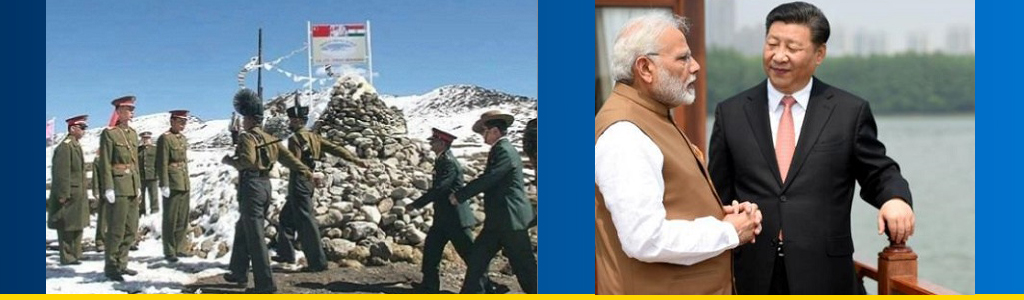

When Modi became prime minister of India in 2014 backed by an impressive parliamentary majority and a reputation for strong and effective leadership, many saw him as similar in mold to Xi. Chinese analysts widely suggested that the two strong, pragmatic and nationalistic leaders could resolve the longstanding and difficult India-China boundary issue. There was also an expectation that both leaders, giving priority to economic development, would leverage the significant opportunities offered by their rapidly growing economies. During their first summit in 2015, they announced a Development Partnership going beyond the Strategic and Cooperative Partnership established in 2005. However, these early expectations were soon belied as China adopted a more aggressive posture on the India-China border, reinforced its alliance with Pakistan, and opposed India at regional and multilateral fora. For example, China prevented a consensus on India’s application to join the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group.

Relations hit a low when Indian military forces prevented a Chinese military crew from constructing a metal road on the Doklam plateau, in Bhutanese territory but claimed by China. This unilateral Chinese action went against an understanding between China and Bhutan that the status quo on their border would not be violated by either side pending resolution of their boundary issue. The Doklam standoff lasted from 16 June to 28 August 2017 during which Chinese rhetoric was vitriolic with the threat of war. Meetings at the leadership level defused the crisis. In a brief meeting on the G20 sidelines in July, Modi and Xi agreed that talks would be held at the official level to resolve the standoff. Limited disengagement of the two sides’ forces followed, enabling Modi to travel to Xiamen for the BRICS summit with Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa in September. One may surmise that the prospect of the BRICS unraveling as a result of India-China tensions may have encouraged China to seek a limited tactical compromise. However, the willingness of the two leaders to convene their rather unusual and unprecedented “informal” summit at Wuhan, April 27 and 28, suggests that Doklam may have triggered a rethink on India-China relations going beyond tactical compulsions.

The informal summit reflects the unusual and somewhat similar leadership qualities of the two men:

One, both leaders have a high degree of self-assurance and belief in the value of leader-to-leader engagement transcending the tools of traditional diplomacy. Over two days they held six rounds of talks including four that were one-to-one with only interpreters present, reflecting a mutual belief in the value of personal diplomacy. Their talks must have covered a great deal of ground, enabling better understanding of each other’s perspective on developments both in their respective countries and the world around them.

Two, statements emerging from the two sides after the summit suggest that the leaders were responding to the growing uncertainty in both the regional geopolitical landscape in Asia and the world. Despite the disruptions caused by US President Donald Trump’s policies, the Chinese had, until recently, been confident about managing US relations, avoiding trade-related disputes and offering cooperation in constraining North Korea from pursuing its nuclear program. This confidence has been badly shaken with China blindsided by developments on the Korean Peninsula where a North-South détente is taking shape without a Chinese role and the prospect of a US-North Korea understanding in the impending summit between Trump and Kim Jong-un not mediated by China. Kim’s two recent visits to China and meetings with Xi have been more of a face-saving exercise for China than reflective of a role in the unfolding, dramatic developments in its own periphery. Coinciding with these developments, serious prospect of a damaging trade war between the United States and China will inevitably sharpen the two countries’ already adversarial security postures. The assumption of a linear and upward trajectory of Chinese power has been shown to be premature, and it’s against this background that China reassesses relations with India. Renewed emphasis on the “strategic and global dimension” of India-China relations goes beyond the dynamics of bilateral relations. This is also reflected in the additional measures announced to strengthen peace and tranquility on their border.

Three, India has also been impacted by the shifting currents in the regional and global landscape, and better relations with China provide the nation with much needed breathing space, particularly in its own periphery. Not that China will give up steady penetration of India’s South Asian neighborhood or the Indian Ocean. However, China may advance at a slower pace than before. Improved India-China relations also constrain the temptation of India’s smaller neighbors to wave the China card in squeezing concessions. The prospect of India and China working together on a joint project in Afghanistan blunts India’s declared opposition to China’s Belt and Road Initiative even as Pakistani concerns about Indian influence in Kabul go ignored. India has made some positive gestures towards China including reverting to its traditional position on the status of the Dalai Lama, foreswearing any official relationship with him or the Tibetan government-in-exile. Taking into account China’s concerns about the emerging security relationship among India, Japan, Australia and India – the so-called “Quad” – Australia may not be invited to join the Malabar maritime exercise this year as was widely expected. This give and take, though limited in scope, represents a significant turnaround in India-China relations from the dark days of the Doklam standoff.

Over the past several years, regular leadership engagement between the two countries at bilateral summits and regional and multilateral fora has played a vital role in keeping their relations on an even keel. Balance has been maintained between the competitive and cooperative components. This balance had been eroding as the power gap between them widened. The Wuhan Summit has restored the balance to some extent, but this can only be sustained if India narrows the gap through more rapid buildup of its economic and military capabilities.

Shyam Saran is a former foreign secretary of India and is currently senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi.