Over the last few years, India and the United States have been at the receiving end of anything but responsible behavior in cyberspace by both state and non-state actors. From the Salt Typhoon campaign that compromised U.S. telecom networks in 2024 to the high-profile cyberattack on India’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences in 2022, cyber operations (including ransomware) have hardly left any sector untouched.

Growing cooperation on the cyber front between New Delhi and Washington has gone hand in hand with the increasing attack surfaces and vulnerabilities of both countries. The United States and India are the most cyber attacked countries in the world, according to a 2024 report by a cybersecurity company, and irrespective of who is in power in America currently, deeper cyber cooperation between the two is of mutual interest. Shared concerns around China’s expanding cyber capabilities in targeting critical infrastructure (including maritime), security of software supply chains, and information warfare campaigns directed at elections amidst an expansive cyberattack surface make cooperation only natural.

The two countries have a history of engagement in other areas of international security. India has demonstrated its commitment to working with the United States on outer space exploration by signing the Artemis Accords in 2023 and most recently, collaborating to send the first Indian astronaut to the International Space Station. Both countries have also worked together on the development of standards for emerging technologies as part of the Quad, a strategic grouping also including Japan and Australia in the Indo-Pacific region. Given their strengths, common interests and existing focus on cybersecurity, the two countries can work with support from other members to position the Quad as a norm builder for four of the 11 UN-recognized, politically-binding norms for responsible behavior in cyberspace: protection of critical infrastructure, responding to requests for assistance, ensuring supply chain security, and reporting of ICT vulnerabilities.

Towards Responsible Behavior in Cyberspace

Much has been written about India’s positions and approaches during international negotiations at the UN Open-ended Working Group on the security in and of information and communications technologies (OEWG) and previously, the multiple Groups of Governmental Experts (GGE) meetings convened on cyber over the years. However, one aspect of India’s approach is often overlooked—it has consistently advocated for responsible behavior in cyberspace. For example, the 2016 U.S.-India framework for their cyber relationship affirmed New Delhi’s commitment to promoting global cyber stability under the UN Charter. More recently, during its 2024 G20 presidency, India advanced this agenda by proposing the Delhi Declaration on responsible cyber conduct. However, while India’s normative positions have been clear, they have struggled to gain traction amid persistent international disagreements.

The broader international landscape has proven resistant to progress on cyber governance. Both UN mechanisms, OEWG and multiple GGEs, have often struggled to achieve consensus on binding norms or laws. Even though an ad-hoc UN committee finally agreed to a draft “United Nations Convention against Cybercrime (Crimes Committed through the Use of an Information and Communications Technology System)”, which was adopted by the General Assembly in December 2024, it is only expected to enter into force when forty states ratify it. Existing frameworks like the Budapest Convention remain outside the UN system and exclude key countries like India.

A political breakthrough did occur in 2015 when UN member-states agreed through the GGE process to voluntarily adopt a framework promoting 11 norms for responsible behavior in cyberspace, covering everything from protection of critical infrastructure to misuse of information and communication technologies (ICTs). This was the first time all states politically agreed to restrain their actions in cyberspace in order to promote responsible behavior, demonstrating the global importance of ensuring supply chain security and the non-acceptable nature of attacks on critical infrastructure. However, in the absence of legal enforcement or penalties for violation, compliance with these norms has been inconsistent.

Considering these global challenges, India has a unique opportunity to promote select UN cyber norms more effectively by deepening cooperation with the United States within the Quad framework. In the Indo-Pacific region, where cyber threats intersect with strategic competition, India can work with Quad partners to operationalize critical norms—including protecting critical infrastructure, improving supply chain security, and curbing cyberattacks on the public sector. By focusing on regional implementation with trusted partners, India can translate normative advocacy into practical action.

In the Indo-Pacific region, where cyber threats intersect with strategic competition, India can work with Quad partners to operationalize critical norms—including protecting critical infrastructure, improving supply chain security, and curbing cyberattacks on the public sector.

Indo-U.S. Cyber Cooperation and the Quad

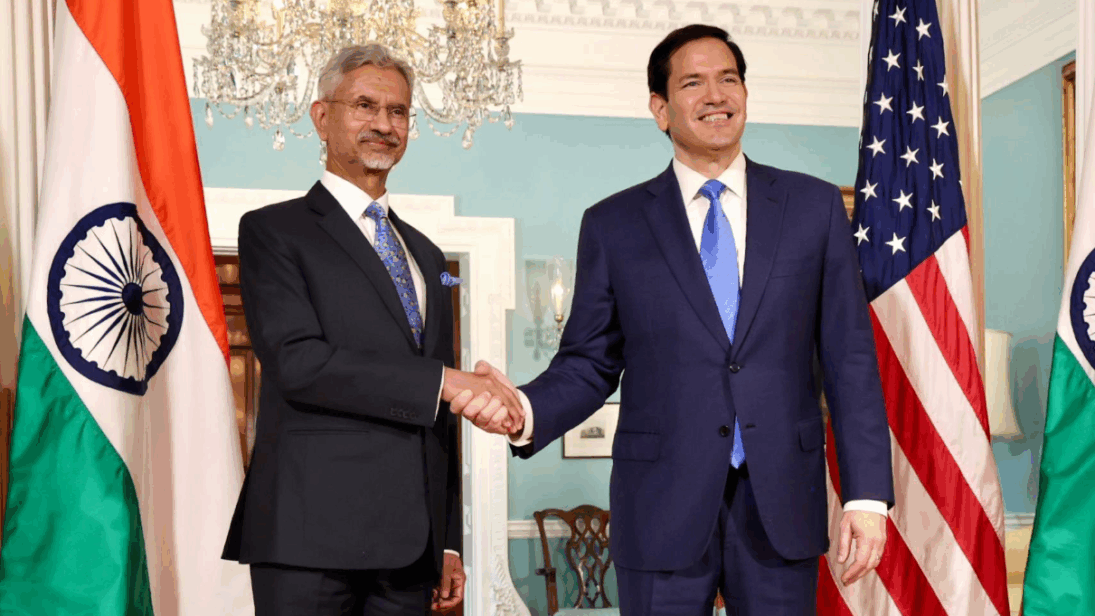

Defined by antagonism and exclusion from multilateral export control regimes for much of India’s independent history, nothing reflected a greater shift in the New Delhi-Washington relationship than the civil nuclear deal in 2005 and India’s Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) waiver in 2008. Ever since, their bilateral technology relationship has only mushroomed, spanning defense, emerging technologies such as semiconductors, and quantum. The U.S.-India initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) (now called TRUST) and the “Quad Principles on Critical and Emerging Technology Standards” best exemplify this growing relationship on the bilateral and multilateral fronts, respectively. Naturally, a focus on cybersecurity has accompanied the broader tech component of the relationship. The “Framework for the U.S.-India Cyber Relationship” signed in 2016, which identified shared principles for collaboration, was an important milestone in the more than two decades of Indo-U.S. cyber cooperation. This framework gave a fillip to the annual bilateral cyber dialogues, which have been ongoing since at least 2013 in some form.

The two countries have also advanced their cybersecurity cooperation through multilateral fora, particularly the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a strategic grouping comprising the United States, India, Japan and Australia. The Quad—first initiated by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007 and revived in 2017—coalesced around the idea of a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) and a shared concern about China’s rise, but in recent years this strategic convergence has come to include critical and emerging technologies as well as cybersecurity due to the national security applications of these technologies.

In recent years, the Quad has convened multiple meetings of the Quad Senior Cyber Group, organized the Quad Cyber Challenge, and agreed on joint principles for a cybersecurity partnership, stating the intent of members to work on areas such as critical infrastructure, cybersecurity, supply chain risk management, software security, and workforce development.

Quad as a Norm Builder

The Quad has the potential to emerge as a norm builder promoting responsible behavior in cyberspace. This potential stems not only from the members’ shared concerns over cyber threats, but also from the group’s strong history of cooperation on technology and cyber issues. All four Quad members have increasingly experienced cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure (especially the energy and telecom sector) and have also been particularly affected by ransomware operations. Some of these attacks have been alleged to have originated from a common source—China. Moreover, the Quad is united by a commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific, grounded in common values like peace, stability, and a rules-based order, making it critical for the group to fight for respect and accountability in cyberspace. In fact, Quad statements in the last few years have even touched on responsible behavior in cyberspace, particularly in the context of taking responsibility for ransomware operations run from a state’s own territory as in 2022 and on capacity building in 2024.

The first step in establishing norms for responsible behavior would involve the Quad members themselves instituting mechanisms for adherence to the same. As Patil, Sarma, and Chandola have argued in their recent paper, the Quad states have divergent cyber incident reporting norms as well as regulations governing protection of critical infrastructure. The authors call for regulatory uniformity among the Quad and recommend the release of joint cyber threat advisories, standardization of cyber incident reporting and investigation norms, and laying out common standards for safeguarding critical infrastructure. Defining these common standards would only take forward what multiple Quad statements have reaffirmed —the need for strong and effective collaboration for the protection of critical infrastructure.

On vulnerability disclosures, Patil, Sarma, and Chandola also suggest that “[t]he Quad countries should develop mechanisms for sharing critical threat and vulnerability intelligence.” As the Snowden revelations demonstrated in 2013, the United States government stockpiles a number of ICT vulnerabilities in the hopes of using these zero-days against adversaries. But some of these stockpiled vulnerabilities may find their way to malicious groups with grave consequences for ICT vendors and users. Instead, wide sharing and dissemination of vulnerabilities would make the cyber domain relatively more secure for all. Thus, the Quad should institute a mechanism for sharing of ICT vulnerabilities first amongst each other and subsequently globally.

Following Israel’s supply chain attack on Lebanon last year and the United States banning connected car technologies earlier this year, there has been a shift in how supply chains are thought of—from “just in time” (efficiency) and “just in case” (resilience) to “just to be secure” (security). The Quad has discussed supply chain issues over the years but the focus has been around energy security or resilience and diversification. On the security front, the focus has been mostly on the software side, with the 2023 statement acknowledging “the security risks posed by lack of adequate controls to prevent tampering with the software supply chain by adversarial and non-adversarial threats.” But a security can also be compromised at the hardware end, as Israel’s pager attack has showcased. The Quad can therefore complement its existing approach with a focus on hardware security to address concerns surrounding sophisticated supply chain attacks. Creating a network of trusted suppliers for critical tech components (say, in the telecom sector) is one way this can be realized. Establishing mechanisms for periodic audits and inspections is another.

To uphold the norm of responding to requests for cyber assistance by other states, the Quad could establish a joint body involving the computer emergency response teams of each member state to respond to cyberattacks on critical infrastructure of affected states in the Indo-Pacific region. This joint body could restrict itself to recovery, investigation and capacity-building while not venturing into the tricky terrain of retaliation. This step would operationalize in a structural manner the Quad foreign ministers affirmation in their 2022 statement “to assist each other in the face of malicious cyber activity.”

Following Israel’s supply chain attack on Lebanon last year and the United States banning connected car technologies earlier this year, there has been a shift in how supply chains are thought of—from “just in time” (efficiency) and “just in case” (resilience) to “just to be secure” (security).

Partnering with the Quad would appeal most to states in the Indo-Pacific region that lack the capacity to deal with common threat actors such as China and North Korea—where most state-linked advanced persistent threat (APT) and non-APT malicious cyber groups are located. To foster trust among states in the Indo-Pacific as well as to realize synergies, the Quad can work with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Such cooperation would meet the Quad’s commitment to ASEAN centrality as well as leverage ASEAN’s history of cooperation on cybersecurity, including through its regional computer emergency response team. While ASEAN has been wary of openly antagonizing China, it has adopted the term “Indo-Pacific” (preferred by the Quad) over “Asia-Pacific,” which is preferred by China. And if Quad cybersecurity cooperation eschews retaliation, as suggested above, ASEAN may find it more palatable to functionally cooperate with the group and solidify its cyber capabilities.

Challenges to Norms in Cyberspace

A major challenge in the way of the Quad upholding norms for responsible behavior in cyberspace would be the different cyber actions and approaches of its member states. While offensive capabilities exist, India, Japan and Australia have historically largely been on the defensive, eschewing escalatory and aggressive offense in cyberspace against various state and non-state actors. But this is now changing, with a shift underway in how the latter two deal with cybersecurity. Japan has recently enacted an active cyber defense law requiring the government to preemptively tackle cybersecurity threats. Australia has focused on developing its cyber offensive capabilities in the last 10 years and has vowed to employ “offensive cyber capability against various adversaries to protect Australians and Australia’s national interests.” However, the most significant challenge to responsible behavior in cyberspace comes from the United States, which, in 2018, adopted an aggressive posture by subscribing to “defend forward” and employ a “persistent engagement” strategy. If what the now-ousted U.S. National Security Advisor Michael Waltz told Breitbart before being sworn in is any indicator of the Trump administration’s approach, then Washington may adopt a more aggressive offensive posture in cyberspace going forward.

It is one thing to do threat mapping, but quite another to degrade capability before a metaphorical bullet is fired—the latter is inherently escalatory. As illustrated in detail by Jenny Jun, “China could erroneously interpret these [United States] actions as a prelude to destructive cyber operations on its own critical infrastructure and/or a signal that the United States is planning to escalate the crisis,” thereby undermining deterrence. Defend forward could also incentivize U.S. adversaries to engage in reckless behavior and, in the quest to deploy before the United States’ discovery, not worry about collateral damage due to unrefined and non-ring-fenced exploits.

The Quad has adopted lofty messaging in the maritime domain of becoming a pillar of stability in the Indo-Pacific region by promoting FOIP. In the cyber domain, the grouping has an opportunity to emerge as a pillar of cyber stability by pushing for the upholding of norms for responsible behavior in cyberspace. However, for this to happen, the United States under Trump 2.0 would have to reconsider its defend forward and persistent engagement strategy while Japan and Australia would either need to scale back their offensive aspirations or set specific, responsible guidelines on when such offensive capabilities would be used.

The article appeared in the southasianvoices