With no formal training, Govindan Gopalakrishnan built at least 114 mosques, four churches and a Hindu temple.

He lingers on a photo of the Beemapally Mosque rising from Thiruvananthapuram’s shoreline. The rose-pink mosque houses the tomb of Beema Biwi, a female Muslim saint believed to be a relative of the Prophet Muhammad.

Gopalakrishnan, a practicing Hindu, was only 29 when he started work on the Beemapally Mosque. In the following decades, the “mosque man,” as he came to be popularly known, has built at least 114 mosques, four churches and a Hindu temple in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

From a family of poor artisans who provided skilled labor to construction projects around Trivandrum, Gopalakrishnan had his first encounter with architecture during his schooldays, when his father, a building contractor in Kerala, would bring home blueprints. Tearing sheets from his notebooks and oiling them, Gopalakrishnan would carefully trace the edifices. Sometimes he visited his father’s work sites to compare the blueprints with the structures under construction.

Govindan Gopalakrishnan poses in the interfaith space in his home in Trivandrum, Kerala, India, Oct. 8, 2023. (RNS photo/Priyadarshini Sen)

Later, a well-known Anglo-Indian draftsman in the city taught him the basics of sketching and drawing. He apprenticed in the public works department, where he received training in building, drafting and site supervision.

It was when Gopalakrishnan’s father received the contract to reconstruct Kerala’s iconic Palayam Mosque in 1961 that the young man began to imagine a calling as an architect. On the work site, he was tasked with supervising labor and became acquainted with the inner workings of a mosque.

The Palayam Mosque’s reconstruction not only increased the family’s popularity within the Muslim community but also paved the way for contracts to spruce up commercial and residential spaces, including that of a Muslim businessman in Trivandrum.

With no formal training in architecture, he relied solely on British historian Percy Brown’s pioneering two-volume book, “Indian Architecture (Islamic Period)” and “Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu),” as the basis to conceive the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture for the mosque.

“The mosque committee had no idea how to raise funds for such a huge project,” said Gopalakrishnan. “The fishermen community simply stepped forward to help through public donations.”

Palayam Juma Mosque in Kerala, India. Photo by Dasika Shishir/Wikimedia/Creative Commons

As the minarets — each measuring 132 feet high — came up, Gopalakrishnan felt certain the fishermen’s offerings had more emotional significance than material worth. They solidified in him a desire to pursue architecture that bound communities together.

“Form and space have never limited him since his imagination comes from an internal space,” said Laxmi Gopalakrishnan, his daughter-in-law who’s a trained architect. “He has no technical expertise or education but the fire in him has produced a wealth of work.”

Govindan Gopalakrishnan is convinced a childhood dream about a serpent scribbling a message on his right palm fueled his desire to draw and design. But it was the community’s support that propelled him forward in the face of many financial and logistical challenges.

We had full faith in his humanism,” said Mohammad Ismail, the president of the Beemapally Islamic council. “Because of him our mosque is considered a mosque for all faiths and not just Muslims; everyone is welcome to pray here or find their oasis of calm.”

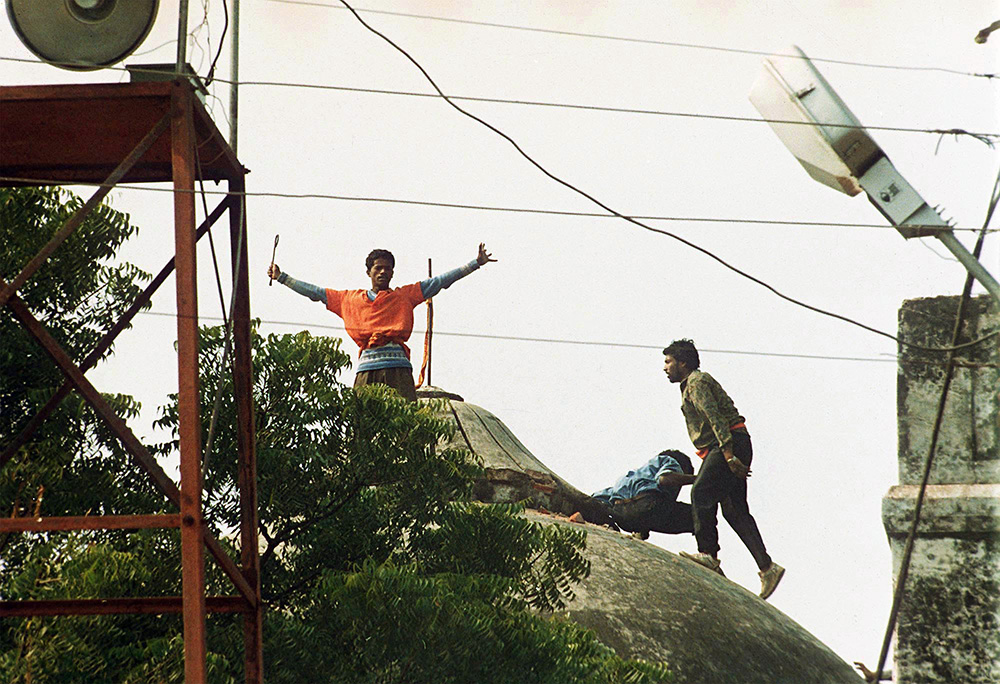

Hindu fundamentalists stand on top of one of the three domes of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, India, on Dec. 6, 1992, after storming the secured site. Thousands of Hindu extremists razed the 430-year-old Muslim mosque to the ground to clear a site for a proposed temple. (AP Photo/Udo Weitz)

When Hindu activists demolished the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya in 1992 and sparked communal riots across the country, some members of the Muslim community appealed to Gopalakrishnan to remove the lotus motif from under the dome of the mosque he had designed for them since the lotus is a symbol of the Bharatiya Janata Party and appears on the images of many Hindu gods and goddesses.

The mosque man soothed tempers by simply saying: “How did a flower become part of any religion? … By designing lotus petals I was expressing my reverence toward it. ”

Gopalakrishnan’s repeated appeals to peace in a time of intense communal polarization and rioting drew the support of Hindu, Muslim and Christian leaders. Not only did they lean on him for moral support, they also encouraged him to construct more places of worship.

The success of Beemapally Mosque led to a slew of religious monuments over the next few decades where he experimented with design, aesthetics, craftsmanship and color palettes.

But the mosque man’s reinvention of traditional architecture did not go without resistance.

When Gopalakrishnan tried to translate into English and local Malayalam the Islamic phrase “There is no God but Allah, and Mohammad is but the messenger of God” at the entrance of a few mosques in Kerala, scholars and some devotees vehemently opposed the move and insisted only on the Arabic writing.

Architect and “mosque man” Govindan Gopalakrishnan has helped renovate the St. George Orthodox Church in Kerala, southern India. (RNS photo/Priyadarshini Sen)

At the Sheikh Masjid — popularly known as the Taj Mahal of Kerala — and the cream-colored Chalai Mosque, his pleas to include the Hindu word “Devam” (for God) alongside Allah in the entrance inscriptions were shot down almost immediately.

Finally, at a 400-year-old mosque in the town of Erumely, Gopalakrishnan managed to inscribe “Devam” at the entrance hall, in hopes of helping the thousands of pilgrims understand the oneness of God.

The spate of mosque constructions inspired Christians and Hindus to come forward.

From 1991 to 2000, Gopalakrishnan renovated St. George Orthodox Church in Chandanapally — an imposing white edifice set amid Kerala’s lush green foliage — and directed his attention to the upkeep of Alinkandam Bhadrakali Temple, which he had built decades earlier.

On Gopalakrishnan’s initiative, Moulavi said, religious leaders have started coming together during Eid, Christmas and local festivals to discuss ways to preserve communal harmony in the city. He’s even spurred churches and mosques to provide shelter to Hindu pilgrims during the Attukal Pongala festival that draws thousands of devotees from across South India. Gopalakrishnan himself observes fast during Eid and Ramadan every year.

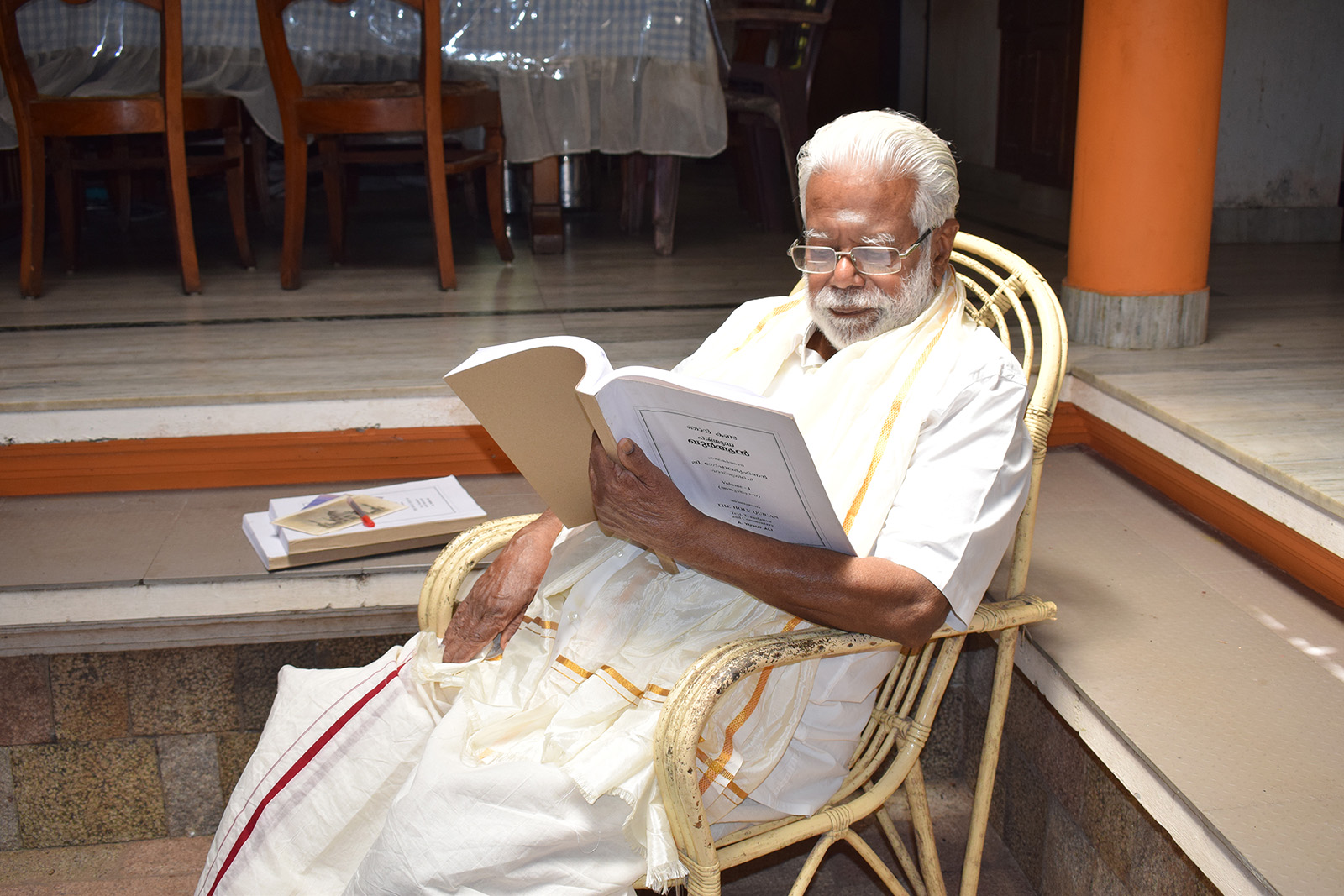

Govindan Gopalakrishnan reads his book “Njan Kanda Quran,” his own interpretation of the Quran, at his home in Trivandrum, Kerala, southern India, Oct. 9, 2023. (RNS photo/Priyadarshini Sen)

At home, he upholds the same pluralism he takes to the community outside.

Every morning, the architect lights an earthen lamp in his prayer room that’s bare of idols and ritual offerings except those gifted by trusted friends and community members. During the day, he writes, reads and discusses ways to promote peace and tolerance in the city.

Two years ago, he completed writing the “Njan Kanda Quran,” which literally means “what I have seen and understood from the Quran” to help people see it as a humanitarian text.

In it, Gopalakrishnan compares Quranic verses with verses in the Bible and Gita to underscore their similarities. The extensive research that incepted 12 years ago spurred him to tap into the complex body of late Vedic Sanskrit texts he’s currently working on.

But his most ambitious plan is to start a school of religious thought in Trivandrum where students can study the Bible, Quran and Gita under a single umbrella and interact with each other without fear.

“We can’t confine God to a specific place or mold him into an idol,” said Gopalakrishnan. “The only way for bigotry and hate to go away is for people to respect each other’s religions.”