Renewed connectivity between India, the Middle East and

Europe shows how maps are temporary, but geography persists.

The newly announced India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) seeks to reimagine the natural connectivity of eras past. Historic trading links between the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East and Eurasia show that long distances are no barrier to shared interests. Indeed, geographical connectivity is what channels trade. However, the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 ruptured India’s historic corridors to the Middle East and Eurasia. Now, Delhi’s strategic impetus is to rejig and rekindle those linkages.

After experimenting with socialist policies of self-sufficiency and import substitution, the pragmatism of economic reform in the 1990s compelled Delhi to look for connectivity linkages to the West, particularly to markets in Europe. Such efforts were held prisoner to the whims of its neighbour, Pakistan. Islamabad routinely refused India’s demands to gain geographical access to the Middle East and Eurasia.

To escape the obstacle, India reached out to Iran. The idea was that Delhi could use Iran’s Chabahar Port as a means of entry into Afghanistan. From there, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) could allow India to reach Central Asia, Russia and Europe. The plan looked perfect on paper. However, Iran’s frosty relations with the United States – India’s most important trade partner – punctured Delhi’s desire to engage Iran as a conduit to Eurasia.

The new IMEC multimodal corridor allows India to bypass Islamabad and Tehran in its quest for connectivity to the Middle East and Europe.

Delhi’s bang for its buck will come from strategically reconnecting with the Arabian Peninsula. Making its way into a regional coalition of like-minded powers to infuse stability and keep China out motivates such a reconnection. A strategic reconnection will have natural spillovers on the security front – a fact that all the participant countries implicitly acknowledge.

How Delhi looks at the Arabian Peninsula has fundamentally changed in the last few years. India is slowly discarding its traditional post-independence reticence for engaging the Peninsula on strategic issues. During the Cold War, Washington’s close relations with Pakistan to promote security arrangements in the Middle East caused much concern in India. Security groupings such as the Central Treaty Organisation were a strict no-no in Delhi.

In the last few decades, India’s growing partnership with the United States, and Washington’s diminishing value for Islamabad, has altered the regional landscape. Greater trust between India and the United States is helping Delhi shed its historic inhibitions about strategic engagement with the Gulf. Set against this landscape, Delhi’s ties with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have grown.

Moreover, India also appreciates that the centre of gravity in the Middle East itself has changed. The Gulf countries have accumulated gargantuan petrodollar reserves – looking for new avenues to pour money into.

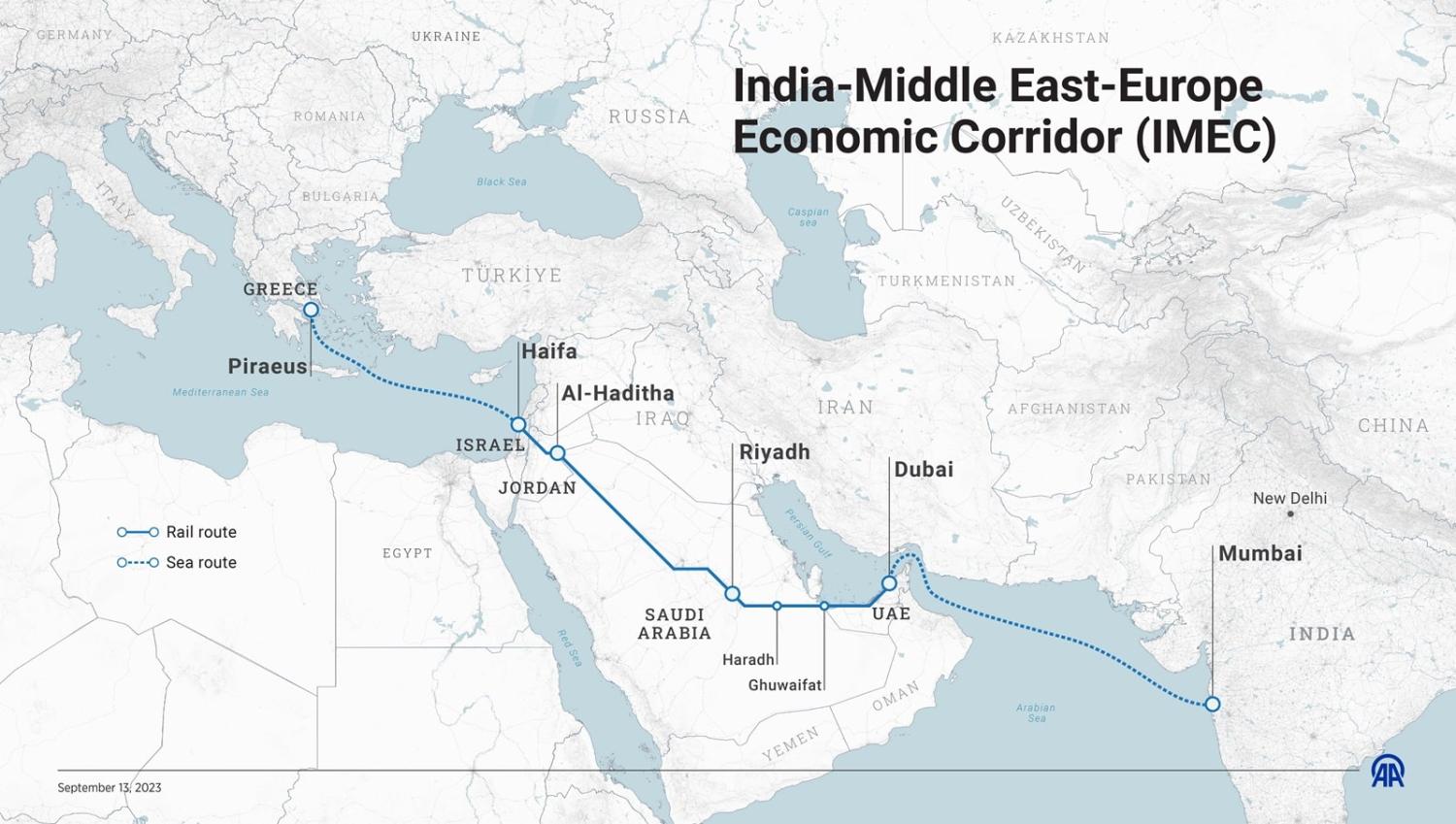

The IMEC project envisages the construction of massive trans-Arabian railway lines across the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Jordan. The two ends of the Middle East will be joined by shipping lanes, connecting Mumbai with Jebel Ali in the UAE, and Haifa in Israel with Piraeus in Greece.

The project also suits the Biden administration’s enthusiasm for working with Delhi in the Middle East, aligning with Washington’s changed regional outlook. Under Biden, the United States is recalibrating its Middle East policy. Since its costly adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan, Washington has been dispensing with the idea of onshore interventions for offshore balancing. Avoiding boots on the ground and relying on maritime power is now the mantra. The US Fifth Fleet patrols the waters of the Arabian Gulf, Red Sea, Gulf of Oman and parts of the western Indian Ocean – with the goal of maintaining regional stability.

A key element of Washington’s offshore balancing is engaging local heavyweights, and it is here that India fits into the puzzle. Active Indian engagement in the Middle East through commercial corridors will inject a dose of economic pragmatism into a region rife with conflict. Washington’s facilitation of normalisation of relations between Israel and several Arab states is part of the same manual. All these measures lower the “political temperature” in the region. However, the fresh tensions in Gaza could become an unexpected speed bump for the IMEC.

Given Washington’s new restraint in the region, Delhi’s growing footprint will have a balancing effect in the Middle East. The India–Israel–UAE–US minilateral arrangement is another example of this emerging trend. The expanding Indian role in the Middle East also offers the Gulf Arabs a new partner for strategic diversification.