AlJazeera

Recent events in the US and violent confrontations between some Hindus and Muslims in England have raised concerns.

In Edison, New Jersey, a bulldozer, which has become a symbol of the oppression of India’s Muslim minority, rolled down the street during a parade marking that country’s Independence Day.

At an event in Anaheim, California, a shouting match erupted between people celebrating the holiday and those who showed up to protest violence against Muslims in India.

KEEP READING

list of 3 items

Hindu nationalists now pose a global problem

Call to end ‘provocation’ after Hindu-Muslim unrest in Leicester

Indian court rejects Muslim plea against Hindu prayers in mosque

end of list

Indian Americans from diverse faith backgrounds have peacefully co-existed stateside for several decades.

But these recent events in the United States – and violent confrontations between some Hindus and Muslims last month in Leicester, England – have heightened concerns that stark political and religious polarisation in India is seeping into diaspora communities.

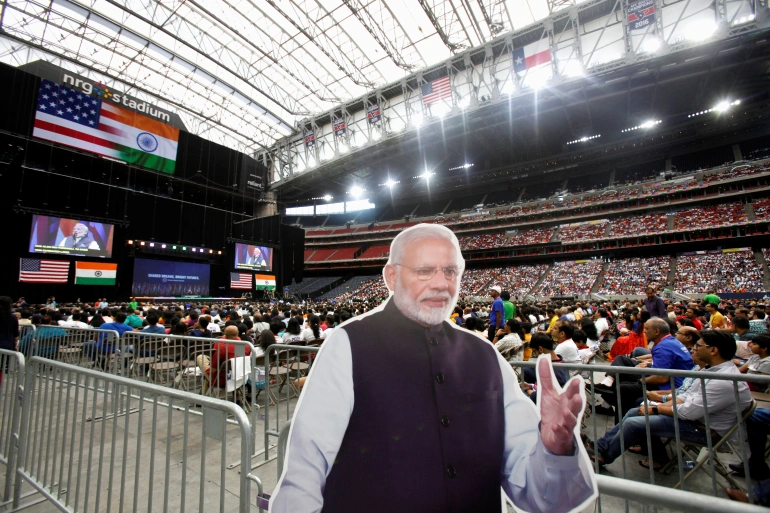

In India, Hindu nationalism has surged under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party, which rose to power in 2014 and won a landslide election in 2019.

The governing party has faced fierce criticism about rising attacks against Muslims in recent years, from the Muslim community and other religious minorities, as well as some Hindus who said Modi’s silence emboldens right-wing groups and threatens national unity.

Hindu nationalism has split the Indian expatriate community just as Donald Trump’s presidency polarised the US, said Varun Soni, dean of religious life at the University of Southern California. It has about 2,000 students from India, among the highest in the country.

Soni has not seen these tensions surface yet on campus. But he said USC received blowback for being one of more than 50 US universities that co-sponsored an online conference called, Dismantling Global Hindutva.

The 2021 event aimed to spread awareness of Hindutva, Sanskrit for the essence of being Hindu, a political ideology that claims India as a predominantly Hindu nation plus some minority faiths with roots in the country such as Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism.

Critics have said that excludes other minority religious groups such as Muslims and Christians. Hindutva is different from Hinduism, an ancient religion practised by about one billion people worldwide that emphasises the oneness and divine nature of all creation.

Soni said it is important that universities remain places where “we are able to talk about issues that are grounded in facts in a civil manner,” But, as USC’s head chaplain, Soni worried about how polarisation over Hindu nationalism will affect students’ spiritual health.

“If someone is being attacked for their identity, ridiculed or scapegoated because they are Hindu or Muslim, I’m most concerned about their wellbeing – not about who is right or wrong,” he said.

Anantanand Rambachan, a retired college religion professor and a practising Hindu who was born in Trinidad and Tobago to a family of Indian origin, said his opposition to Hindu nationalism and association with groups against the ideology sparked complaints from some at a Minnesota temple where he has taught religion classes.

Accusations of Hindu nationalism

On the other hand, many Hindu Americans feel vilified and targeted for their views, said Samir Kalra, managing director of the Hindu American Foundation in Washington, DC.

“The space to freely express themselves is shrinking for Hindus,” he said, adding that even agreeing with the Indian government’s policies unrelated to religion can result in being branded a Hindu nationalist.

Pushpita Prasad, a spokesperson for the Coalition of Hindus of North America, said her group has been counselling young Hindu Americans who have lost friends because they refuse “to take sides on these battles emanating from India”.

“If they don’t take sides or don’t have an opinion, it’s automatically assumed that they are Hindu nationalists,” she said. “Their country of origin and their religion is held against them.”

Both organisations opposed the Dismantling Global Hindutva conference, criticising it as “Hinduphobic” and failing to present diverse perspectives.

Conference supporters said they rejected equating calling out Hindutva with being anti-Hindu. They said proponents of Hindutva, including Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – the ideological mentor of Modi’s BJP – aimed to make India a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation) in which minorities will are second-class citizens.

Some Hindu Americans, such as 25-year-old Sravya Tadepalli, believed it is their duty to speak up. Tadepalli, a Massachusetts resident who is a board member of Hindus for Human Rights, said her activism against Hindu nationalism is informed by her faith.

“If that is the fundamental principle of Hinduism, that God is in everyone, that everyone is divine, then I think we have a moral obligation as Hindus to speak out for the equality of all human beings,” she said. “If any human is being treated less than or as having their rights infringed upon, then it is our duty to work to correct that.”

Tadepalli said her organisation also works to correct misinformation on social media that travels across continents, creating hate and polarisation.

Tensions in India hit a high in June after police in the city of Udaipur arrested two Muslim men accused of slitting a Hindu tailor’s throat and posting a video of it on social media. The slain man, 48-year-old Kanhaiya Lal, had reportedly shared an online post supporting a governing party official who was suspended for making offensive remarks against the Prophet Muhammad.

Hindu nationalist groups have attacked minority groups, particularly Muslims, over issues related to everything from food or wearing head scarves to interfaith marriage. Muslims’ homes have also been demolished using heavy machinery in some states, in what critics call a growing pattern of “bulldozer justice”, in disregard to “due process” and “rule of law”.

Such reports have Muslim Americans afraid for the safety of family members in India. Shakeel Syed, executive director of the South Asian Network, a social justice organisation based in Artesia, California, said he regularly hears from his sisters and senses a “pervasive fear, not knowing what tomorrow is going to be like”.

Syed grew up in the Indian city of Hyderabad in the 1960s and 1970s in “a more pluralistic, inclusive culture”.

“My Hindu friends would come to our Eid celebrations and we would go to their Diwali celebrations,” he said. “When my family went on summer vacation, we would leave our house keys with our Hindu neighbour, and they would do the same when they had to leave town.”

Syed believed violence against Muslims has now been mainstreamed in India. He has heard from girls in his family who are considering taking off their hijabs or headscarves out of fear.

‘Behind closed doors’

In the US, he sees his Hindu friends reluctant to engage publicly in a dialogue because they fear retaliation.

“A conversation is still happening, but it’s happening in pockets, behind closed doors, with people who are like-minded,” he said. “It’s certainly not happening between people who have opposing views.”

Rajiv Varma, a Houston-based Hindu activist, held a diametrically opposite view. Tensions between Hindus and Muslims in the West, he said, are not a reflection of events in India but rather stem from a deliberate attempt by “religious and ideological groups that are waging a war against Hindus”.

Varma believes India is “a Hindu country” and the term “Hindu nationalism” merely refers to love for one’s country and religion. He views India as a country ravaged by conquerors and colonists, and Hindus as a religious group that does not seek to convert or colonise.

“We have a right to recover our civilisation,” he said.

Rasheed Ahmed, co-founder and executive director of the Washington, DC-based Indian American Muslim Council, said he is saddened “to see even educated Hindu Americans not taking Hindu nationalism seriously”. He believed Hindu Americans must make “a fundamental decision about how India and Hinduism should be seen in the US and the world over”.

“The decision about whether to take Hinduism back from whoever hijacked it is theirs.”

Zafar Siddiqui, a Minnesota resident, hoped to “reverse some of this mistrust, polarisation” and build understanding through education, personal connections and interfaith assemblies. Siddiqui, a Muslim, has helped bring together a group of Minnesotans of Indian origin – including Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and atheists – who meet for monthly potlucks.

“When people sit down, say, over lunch or dinner or over coffee, and have a direct dialogue, instead of listening to all these leaders and spreading all this hate, it changes a lot of things,” Siddiqui said.

But during one recent gathering, some argued about a draft proposal to, at some point, seek dialogue with people who hold different views. Those who disagreed explained that they did not support reaching out to Hindu nationalists and feared harassment.

Siddiqui said that for now, future plans include focusing on education and interfaith events spotlighting India’s different traditions and religions.

“Just to keep silent is not an option,” Siddiqui said. “We needed a platform to bring people together who believe in peaceful co-existence of all communities.”