As a vibrant and resurgent Asia improves trade with the outside world, a plethora of multi-modal connectivity projects has underscored the urgency of land and sea infrastructure creation in the region. From an Indian and South East Asian perspective, the key connectivity project is the 3200 kms trilateral highway connecting India, Myanmar and Thailand. The highway forms part of East-West economic corridor linking India with Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Launched under the auspices of the Mekong Ganga Cooperation, and later incorporated into the transport sector of Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), the trilateral highways project had been in a financial and political limbo for the past few years. Last year, however, things began looking up with New Delhi attempting a fresh revival of the languishing project.

After India’s Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh held detailed talks on rejuvenating the project with his Thai counterpart Yingluck Shinawatra in February last year, a high level delegation from Thailand came on a short tour of Manipur in India’s northeast a few days ago. During the visit, optimism abounded about the prospects of a sudden spurt in trade and commerce growth once the proposed highway was opened for use. The focal point of the project is Manipur’s Moreh town in Chandel district that was recently connected with Myanmar. Renewing its commitment to building the highway, India recently allocated a substantial sum for the upgrade of the 160-km-long Tamu-Kalewa-Kalemyoroda road which connects Moreh to central Myanmar’s Ri-Tiddim road. India also granted a US$500-million loan to Myanmar, part of which is meant for the construction of the trilateral highway. Needless to say, the highway has evoked considerable interest in South East Asian countries that see the opening of Moreh as a tangible manifestation of India’s Look-East policy.

And while India, Myanmar and Thailand are combining their efforts to make the Asian highway dream a reality, it is being fervidly supported by the U.S. that sees the project as an encouraging sign of closer ties between Asia’s free-market democracies – a relationship that can help balance China’s rise. Meanwhile, more pieces of the ambitious project feel into place with Vietnam completing its section linking Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar last year.

The Asian Highway Project

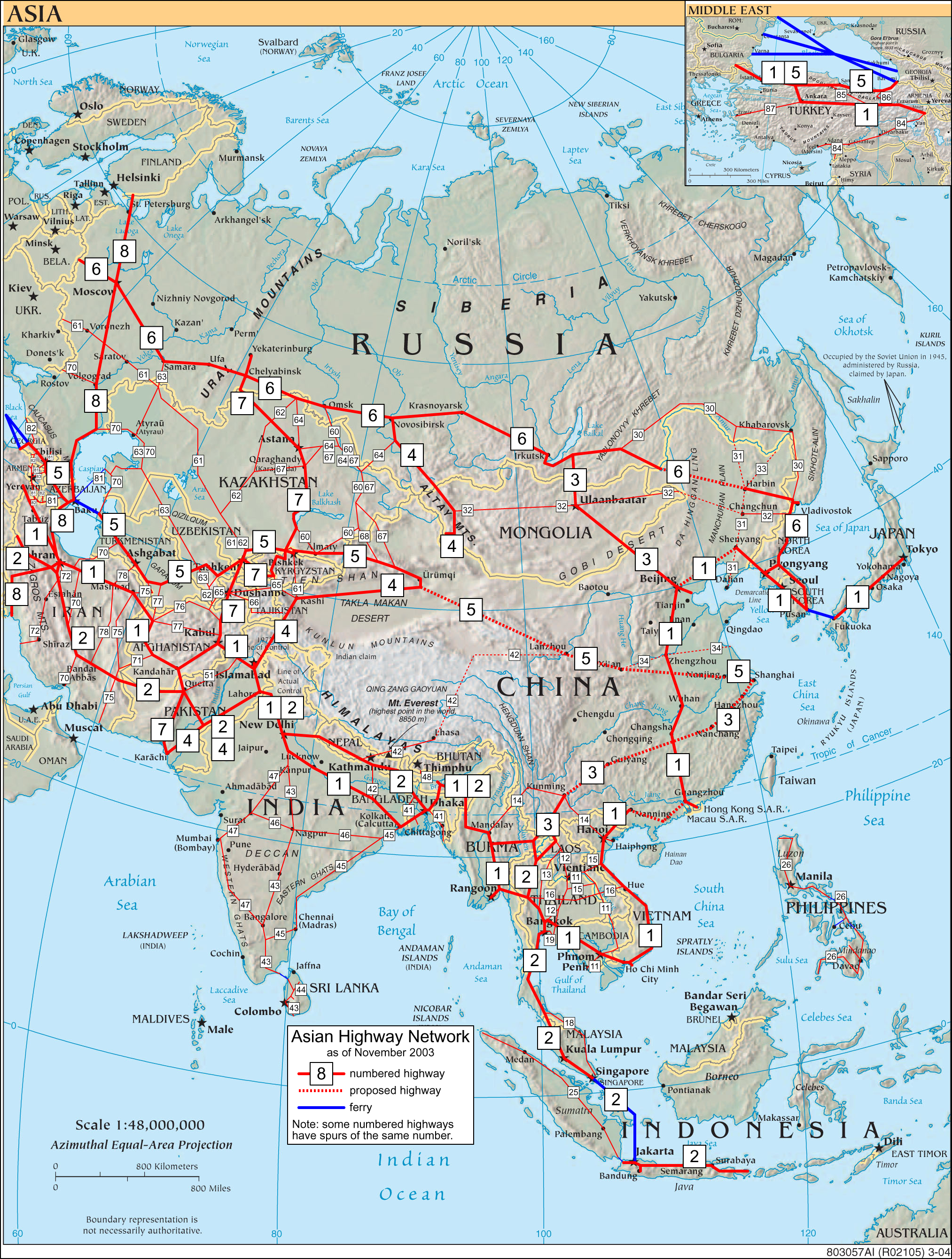

The trilateral highway is important because it will connect India, Myanmar and Thailand with the Asia Highway (AH) Project, a multinational venture of mammoth proportions that seeks to integrate nations in Asia with Europe. Industry estimates suggest that seamless connectivity with the Asian Highway Network through the trilateral project could ratchet up India’s trade with ASEAN to about US$100 billion in the next five years. The project envisages the construction of a Trans-Asian Highways to be undertaken as a cooperative project by countries in Asia and Europe and supported by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). It forms an important pillar of the Asian Land Transport Infrastructure Development (ALTID) project, and comprises the Asian Highway, the Trans-Asian Railway (TAR) and land transport projects

The AH project is emblematic of the broader political developments in Asia. The hectic confabulations and tortuous negotiations between stakeholder nations (32 of them) – many of which initially resisted but eventually allowed the highway to cross-over their land territories – reflects the challenges that confronted the project. The funding for the venture was provided for by both advanced Asian countries like Japan, China and India as well as international agencies such as the Asian Development Bank. However, even until last year, there were doubts on the certainty of the funds being made available.

The progress on the ground though, has been tangible. Over the years the AH project has expanded in stages, and now comprises over 141,000 km of roads through 32 of the UN ESCAP member countries. Eventually, the AH is planned to extend from Japan in the east to Turkey in the West, and Russia in the north to Indonesia in the south. The Asian states that stand to gain the most from this project are tourism-driven economies such as that of Thailand, and trade-driven ones, such as China. While a total of 5,111km of the AH network runs through Thailand, China accounts for 25,579 km of the planned route. Meanwhile, India has 11,432km highway designated as part of the AH.

The undertaking, however, hasn’t been without its share of controversy. There have been strong environmental concerns over the development of highways, even though every effort is being made to balance the downsides with economic benefits. There has also been, for many years now, a debate raging on the privatization of segments of the highway network. Asian highways have increasingly come to be seen as a part of the growing highway economy worldwide, in which highways are increasingly operated as for-profit assets. The proposition to privatize highways however has found little consensus. Meanwhile, the politics behind the AH network has been quite fierce. Bangladesh opted out of the Asian Highway, because of fears of giving India connectivity through its territory, only underscoring the vulnerability of trans-national projects to domestic and regional politics.

The New Silk Route

At the heart of the development of connectivity in Asia lies an emerging vision to revive the old Silk route via a combination of modern highways, rail links and energy pipelines running across the Eurasian landmass. The idea was first mooted in 1959 by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) when it proposed the initiation of a Trans-Asia Railway. But a substantive consideration of the plan came about in the 1990s when the Trans-Asian Railway and a New Silk Road began to appear in both Chinese and American narratives. The USA and China have both, in the years since, actively sought to revive the Silk Road in a modern form. Each however has a different understanding and appreciation of the concepts, expectations and intentions for a New Silk Road.

While the US emphasizes connecting Afghanistan with South, Central and South-West Asia, the Chinese seem more interested in connecting East Asia with the Western Europe. The Chinese concept of a New Silk Road is based around over forty thousand kilometers of railways in three corridors across the Eurasian continent dubbed the ‘Eurasian Land Bridge’. The first of these uses the Trans-Siberian Railway between Vladivostok and Western Europe, and was completed in 2008. The second runs from Lianyungang Port, through Kazakhstan and eventually terminating at Rotterdam, which completed testing in 2011. The third begins at the Pearl River Delta, running through South Asia before also terminating at Rotterdam, but is not yet finished.

While China’s New Silk Road construct focuses on the possibilities of economic growth, the US appears more concerned with the political dimensions of the changes that will come about as a result of better connectivity in Europe and Asia. The US motivations for the New Silk Road, therefore, address security issues such as denying safe havens for terrorists, WMD proliferation and the need for energy and stability in the region. While preparing Afghanistan’s economy for post-2014 withdrawal of coalition forces remains the centre-piece of the American strategy, the US’ plans to revive the ‘Silk Road’ also aim to enable Central Asian states to boost economic activity, providing regional stability, and thwarting Soviet influence. For the U.S., the New Silk Road is as much about maintaining and protecting its influence in Asia and the Middle East, as it is about promoting regional economic growth

The difference between the American and Chinese motivations for building the silk route is stark and bears close analysis. It highlights the potential dangers of both powers acting on the project with only their vested intentions in mind, many specific to the Silk Road project such as the American desire to improve the future of Afghanistan, while maintaining its influence in Central Asia and the Middle East. The asymmetries in objectives could, in the future, lead to the sharpening of Sino-US rivalry in Asia.

A Costly Enterprise

Regardless of the politics behind developments of highways in Asia, there is little to deny the mammoth costs of building the infrastructure. A joint study by the Asian Development Bank, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and the World Bank in 2005 showed the AH project needed about $170 billion worth of investments into road building between 2006 and 2010, or $34 billion per year. More recent figures show the figure to be closer to $2.3 trillion over the period 2010-20, or $234.1 billion per year, both for new roads and maintenance. However one sees it, the Asian highway (AH) network has the potential of an important building block for pan-Asia integrated inter-modal transport system.

The Stillwell Road

For India, developing its northeast goes beyond construction of the Asian Highway. After losing out to China in the construction of an important stretch of the historic Stilwell Road that once connected Ledo in Assam to Kumming in China, India, in 2012, decided to renew its pitch to build a key section of the historic Stilwell Road and the Imphal-Mandalay route to promote cross-border trade and economic growth in Northeast states. Myanmar had awarded the contract of the World War II road, linking Myitkyina in Kachin state to Pangsau Pass on the Arunachal Pradesh border, to a Chinese company — the Yunan Construction Engineering Group — in 2010. This resulted in some unease in New Delhi leading to the decision to make a fresh bid for building the road.

China, it may be instructive to note, has planned the construction of a Pan-Asia Railroad, which, when complete, will form an enormous circular route. Starting in Kunming in Yunnan Province, it is planned to extend through Myanmar and south to Bangkok, where a spur will traverse Malaysia to Singapore. From Bangkok, the line will run east through Cambodia and north through Vietnam to Hanoi, then through Laos and back to Kunming. There are, in addition, two other projects that China has planned; the first, from Urumqi to Germany through Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey; and second, from Heilongjiang in northeast China to southeastern Europe via Mongolia and Russia. With these three railroads in place, China’s transit dominance of South, Central and East Asia will be near complete.

For now, India is focusing on the Stilwell road. Built by General Joseph Stilwell during World War II to outflank the advancing Japanese army and establish a land supply route to China, the road is seen by many in India as a gateway to Southeast Asia. It has the potential to bolster India’s Look East policy and facilitate trade by opening border points. But getting the opportunity to build a key section of the road can also assist India in countering China’s pervasive influence in the region.

Even if China eventually bags the project to construct the road, for India it would be a good thing. New Delhi has, since 2010, been involved in the development of the Sittwe Port, situated at the mouth of the Kaladan River in Myanmar. It is part of the Kaladan Multi-modal Transit Transport Project, a collaborative venture between India and Myanmar. That project will bring the Northeast closer to a commercial sea route, via the Kaladan River and a highway linked to a network of roads in the region. Besides, the AH highway through Moreh could eventually become part of a trans-Asian road system, that could help develop and integrate the Northeast.

Clearly, with the Asian connectivity networks, the possibilities are infinite. All that is needed among the stake holders is clarity and unity of vision.