This article is part of a series called “Heroes And Sheroes Of Plural India” under #AnHourForCommunalHramony campaign to celebrate the Heroes and Sheroes who struggled to shape modern India in all its plurality. Today we celebrate Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain a pioneering woman literary person who also pioneered girls education . All are welcome to contribute an hour of your day, in celebrating these Heroes and Sheroes of plural India

I would like to begin this piece by first delineating the importance of this initiative for me, the importance of again celebrating the plurality of this nation, the importance of revisiting the glorious chapters of our past, some widely known, some less so, and some, may be, completely unknown. The significance of indulging in this exercise, especially now, can at best only be understated. First and foremost, it can never be out of context to remember and to celebrate those on whose shoulders we are standing today and are being able to look as far ahead as we are able to. Secondly, in the present day and age, when the fundamentals of existence are themselves being challenged openly, when an attempt is being made to rob the nation of its longstanding and most natural cultural heritage of plurality and peaceful and harmonious co-existence, when histories are being re-written and statement of facts being convoluted and contorted to the extent that they become totally unrecognizable and when there is a conscious attempt to direct the collective energies of the nation only in these directions, then it is high time that what is actually significant and meaningful is brought to the forefront. Revisiting the lives of these sung and unsung heroes and sheroes will familiarize us with our past, will inform us of the multitude of people that have existed in the past and achieved that which might have seemed almost impossible if seen within the context of the day and age, will inspire us to move towards our goals with renewed vigor and will celebrate what is really worth celebrating – the tireless efforts of people to uphold the rich cultural heritage of our nation that has taught us to stand for plurality and for amelioration of the ills plaguing our society, those of differentiations based on caste, religion, gender, language, region, ethnicity etc. This series, for me, is a celebration of those who have dared to dream and have fought against all odds to try and realize their dreams. Some of these have fought for religious and communal harmony, some have fought for amelioration of gender differences, some have stood for the rights of ethnic minorities, and so on and so forth – the list is endless. Some of the people figuring in this series, and their work, may be very well known, some may be those who are known but their work and their message forgotten and some those who are as yet unknown or little known, despite having done significant work.

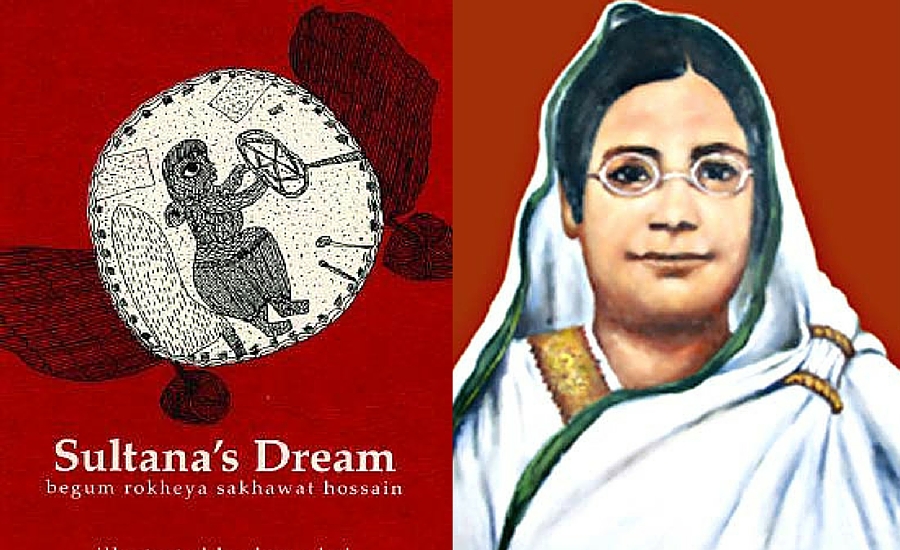

Through this article, I wish to discuss the life and work of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. Some would have heard about her, some would have read about her and her work and some probably would not be knowing about her. There are various existing competent sources that aptly talk about her life and her work. My purpose here is to not say anything about her that may not be existing in the public domain already. My purpose, however, is to try that more and more people get to know about her and the tremendous contribution made by her towards women education, specially, Muslim women.

“Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was born sometime in 1880 in the district of Rangpur in a village called Pairaband in British Indian Empire. She was also known as Roquiah Khatun at birth. Her father Zahiruddin Mohammad Abu Ali Saber was well educated, bilingual and a landowner. Rokeya’s father had four wives and her mother was Rahatunnessa Sabera Chowdhurani. Chowdhurani birthed two sons and three daughters, of which Rokeya was one.” (Hakeem, 2015).

Rokeya was born in a traditional conservative Muslim family of Bengal in British India (now in Bangladesh). As was the prevailing custom in those times, the education of girls was not given much importance. Even if considered worthy of being imparted any kind of education, it was felt that women need to be educated either about religious matters or about their duties as wives, mothers, daughter-in-laws and homemakers. Born in such an environment, Rokeya was blessed to have the unfettered support and guidance of one of her elder brothers and her elder sister. “At the dead of night when the entire household was fast asleep, Rokeya’s brother would teach her Bangla and English secretly under the glow of candles. Rokeya could learn Bangla due to the assistance and encouragement that she received from her elder sister Karimunnessa, a lady of great qualities and extraordinary courage. (Murshid 172) In an era when women’s education was frowned upon, Rokeya’s brothers secretly taught her to read and write English and Bangla.” (Mahmud, 2016). “Rokeya‟s second phase of inspiration came from her husband Sakhawat Hossain. He was highly educated, progressive and a real gentleman who believed in the education of women. He always inspired her and opened a wider world to apply her dream with courageous steps. Under Sakhawat’s influence Rokeya began to write about her thoughts on social issues of womanhood and women’s degradation. (Hossain 79)”. (Mahmud, 2016).

Though lucky to have such positive influences in her life, Rokeya was also unfortunate to lose her husband and her two infant children, at the age of five months and four months. Yet, with her daunting and unwavering spirit and strength of character, she went on to read and write and produced works that were much ahead of her times. She also opened a school for Muslim girls and campaigned widely for women education, especially that of Muslim women.

“Rokeya’s writings are not voluminous but full of significance. Her literary career starts in 1902. The first composition is “Pipasa” (The Thirst). Most of her writings are in Bengali. These include two anthologies of essays, satires, short stories which are entitled Motichur and divided into two volumes– Motichur- I (1904) and Motichur- II (1922), a novel– Padmarag (1924), Avarodhbasini (1931), a narration of 47 historical and true events of the miserable plight ad indignities which women have suffered in the name of purdah. She also wrote a few works in English. The most famous of those is Sultana’s Dream (1908). Other than Sultana’s Dream, she also wrote two essays– “God Gives, Man Robs” (1927) and “Educational Ideals for the Indian Girls” (1931) which were published in The Mussalman magazine. Besides, she has some unpublished essays, short stories and comic strips. She also wrote several poems in various magazines.” (Mahmud, 2016).

Her most popular work, Sultana’s Dream is a fictional work where she dwells into a utopian world in which the roles of men and women have interchanged. Comparing the practice of purdah to seclusion, in Sultan’s Dream, Rokeya creates an imaginary world called ‘Ladyland’, where men are so ‘secluded’. “On page fifty-seven of Sultana’s Dream, I will summarize her story as a simple story of a woman that is dreaming and happens to visit a land where men are confined in a system called mardana and women bear the responsibility of advancement in society. The land is called “Ladyland,” where there is law and order. The land is devoid of violence, corruption and crime.

The people of “Ladyland” have learned to appreciate Nature and treat each other with respect and love. In “Ladyland,” child marriage is banned and education is encouraged amongst women.

Quayum, the editor of The Essential Rokeya, explains Sultana’s Dream here: “In other words, the people of this land do not care about any extra-terrestrial power or adhering to a set of senseless rituals, but only the values that are directly beneficial to the human community and to the human soul” (Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, 1988, pp. 1-2).” (Hakeem, 2015).

Her take on the practice of purdah is also to be noted here, where she differentiated between the negative impact of the practice in that it ‘secludes’ women, at the same time, personally not being against adorning it as a way of dressing that she preferred. Thus, her call for emancipation of Muslim women was much deeper than the superficial aspects of how to dress etc. Her emphasis was on the provision of equal rights to women to educate themselves and fulfil their dreams and hence, break the shackles of the ‘secluded’ environment that is forced on them by the patriarchal set-up of society.

Her work, Sultana’s Dream, is also path-breaking in terms of the creativity and imagination that has gone into this writing. To write a novel that creates a utopian world and to convey a social message through it, was an exemplary accomplishment at the time. If Ayn Rand’s writings, “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged” are best-sellers today, there is no reason why this visionary piece of work by Rokeya should not be treated as equally powerful, in the same genre of writings, that of utopian novels. The social structure of society existing in her time, despite which Rokeya was able to accomplish this feat, makes this work and other works written by her, all the more worthy of admiration. Her untiring efforts in spreading education among Muslim women by running a school and convincing families to send their girls to study are extremely praiseworthy and worth emulating.

Today, more than a century after Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain fought for the education and emancipation of women, this issue still plagues our society. There are people still fighting for the liberation of women. A century has not been enough time for us to provide equal status to women, as is provided to men. Yet, instead of trying to eradicate evils like gender discrimination from our society on a war footing, all the energies are being directed at proving a false sense of nationalism. The greatness of our cultural heritage is from such people, who have visualized much ahead of their times and have left no stone unturned in working towards their vision. This is the need of the hour, for us to know about such gems of our historical past, draw inspiration from them and chart the course of history in a direction that triumphs the principles of humanity.

References

Hakeem, S. (2015). The Writings of Rokeya Hossain: A pioneer of her time whose writings hold relevance today.

Mahmud, R. (2016). Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain: Tireless Fighter of Female Education and their Independence – A Textual Analysis . International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) , 40-48.

Nivedita Dwivedi has done MA in Elementary Education from Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

The article appeared in Countercurrents on July 27, 2017