Abstract:

Health is a fundamental element of human development. The share of government expenditure on healthcare is decreasing in Bangladesh for the last few consecutive years which is resulting in several burdensome problems in the country. The purpose of the paper is to analyze the trend of budget allocation in the health sector of Bangladesh. Last six year in Bangladesh, allocations in the health sector are around 5 percent of the total budget. The paper identifies the impacts on society of financial scarcity in healthcare. As a result, Out-of-pocket expenditure in the health sector rose to 71% in 2015 which was 60% in 2008. The higher OOP is enough to discourage poor people from using health care services which damage their health further because of negligence. The decreasing rate of the budget in health sectors also producing problems like overburden on poor, inadequate health infrastructure with lack of quality and increase of non-communicable disease.

Key

words: Health financing, Out-of-pocket expenditure, quality,

healthcare infrastructure disease burden, Bangladesh.

Introduction:

It does not mean health should be undervalued because health comes after food and shelter in basic needs approach. Someone suffering from any acute disease cannot live happily no matter how much food she consumes. Health is now universally an important index of human development [1]. It is mutually the cause and effect of poverty, illiteracy, and ignorance. Policies for human development not only raises the income of the people but also improve other components of their standard of living, such as life expectancy, health, literacy, knowledge, and control over their destiny and using these components the UNDP measures standards of living in a country by Human Development Index.

Bangladesh has made substantial progress in most of the health indicators over the last two decades [2]. Bangladesh has successfully achieved MDGs goal 4 and 5; reduce child mortality and improve maternal health. Bangladesh has now the lowest total fertility rate and the lowest infant and under-5 mortality rates in South-Asia [3 & 4]. Under-5 child mortality decreased significantly from 144 to 41 per 1,000 live births and maternal mortality rates have also dropped by 66 percent [5]. Although Bangladesh has reduced child mortality rates, quality of healthcare facilities in public hospitals and community clinics is still low. Majority of the poor people still depends on government health structures for remedies from illness in Bangladesh [6]. In Bangladesh, 24.3 percent people are still living below the poverty line and 12.9 percent people of the total population are under extreme poverty [7]. Inequalities exist in almost all sectors but inequalities in the health sector have more negative impacts than in other sectors [8 & 9]. Poor people, low-income people and slum dwellers of Bangladesh have less accessibility in healthcare facilities. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), allocation in the health sector has to be at least 15% of the total budget of a country [10]. In Bangladesh, public expenditure of total budget in the health sector is too low. In FY 2018-2019, public health expenditure is only 5% of the total budget [11]. As a consequence, the low rate of budget allocation in the healthcare sector has increased out of pocket expenditure in Bangladesh. The out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditure in Bangladesh is 63 percent of the total health expenditure, which is much higher than that of the world average of 32 percent [12] which is hard to maintain for people under poverty line. Besides, quality of healthcare services in public hospitals is very low. In Bangladesh, number physicians and nurse/midwives are 3.0 and 2.8 per 10000 populations whereas the number of hospital beds is 4 [13] which are the lowest in South Asian countries. Due to the scarcity of budget and less accessibility of people in health care, the death rates of people by unaffected diseases are increasing in Bangladesh. In 2017, the death rate of unaffected diseases has increased to 67% [14]. However, poor access to services, low quality of care, and the high rate of maternal mortality and poor status of child health still remain as challenges of the health sector [15].

The main objectives of the paper are: (1) analyzing the trend of public expenditure in the health sector by the government in Bangladesh. (2) Identifying the impacts on society due to financial scarcity in healthcare.

Literature Review:

In a paper on ‘Health System Financing in Bangladesh: A Situation Analysis’ by Anwar Islam et al. explained that Bangladesh government spending on healthcare is decreasing in the last few years[16]. Also, the government is spending only about 3.5% of GDP in healthcare and it results in 63% of the total out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare. Healthcare in Bangladesh still lacks quality healthcare services despite all the achievements in MDGs. The authors suggest that governments should spend more on healthcare sector alongside with searching alternative sources of funding [16].

A paper on ‘Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries’ by Peters, D et al. indicated that minute budget in healthcare as a common incident in contemporary low and middle-income countries compared to developed countries [17]. The reason behind inequitable healthcare access across regions is four-dimensional including financial and Geographic Accessibility, availability and acceptability though it is not always the case because government and NGOs can reduce inaccessibility by reaching the poor [17]. They suggested that new innovations in health sectors should be used to increase healthcare services.

A study named “Healthcare Financing in Bangladesh: Challenges and Recommendations” done by Hassan et al. explained that over last seven year, budgetary allocation in the health sector has declined from 16.2 percent to 4.3 percent. As a result, healthcare services in public healthcare are inadequate and inefficient [18]. These problems lead to increase profiteering tendency private care sectors. The paper also mentions that the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer etc are increasing in Bangladesh [18].

A paper on “Who pays for healthcare in Bangladesh? An analysis of progressivity in health systems financing” by Molla and Chi (2017) state that health care financing is regressive in Bangladesh. It has pushed high out-of-pocket payment (OOP) which caused income inequality in society [19]. The study showed that social insurance for poor, elderly, disable and disadvantage is very negligible but private health insurance is present only in some pocket area. As a result, “heavy reliance on OOP payments has reduced household living standard and may lead to poverty or deeper poverty”[19].

Trends of health expenditures in Bangladesh:

The Government of Bangladesh is constitutionally committed to ensuring the provision of basic medical requirements to all segments of the population in the country. The Government’s vision for the health, nutrition and population sector is to create conditions whereby the people of Bangladesh have the opportunity to reach and maintain the highest attainable level of health [20]. World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that a country should allocate in the health sector at least 15% of the total budget [10]. Unfortunately, Bangladesh is still a far away from the required level of allocation in healthcare of yearly budget which is set by WHO. In FY 2018-2019, Bangladesh has allocated only 5.03 percent for public health services in the total budget [11]

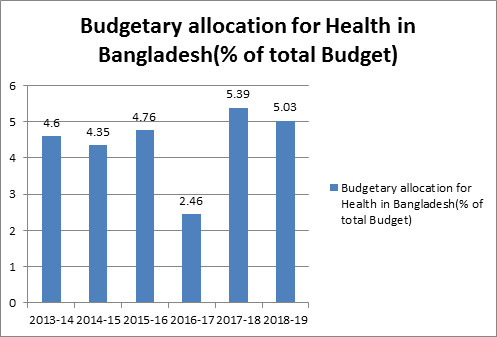

Figure 1: Trend of budgetary allocation for Health in Bangladesh (in percentage of total Budget).

Figure 1 shows the trend of budget allocation in the health of the past six fiscal years in Bangladesh. The figure indicates that during the last six years, Government expenditure on health care in the proportion of total budget has not increased. Last six-year, allocations in the health sector are around 5 percent of the total budget. Moreover, the allocation in healthcare has been stagnant in lower rate whereas population, as well as different type of new diseases, increased within the same time period. In FY 2013-14, the allocation for health was 4.6 percent of the total budget and it still only in 5 percent in FY 2018-19. The government expenditure in healthcare has not increased compared with the demand for healthcare services.

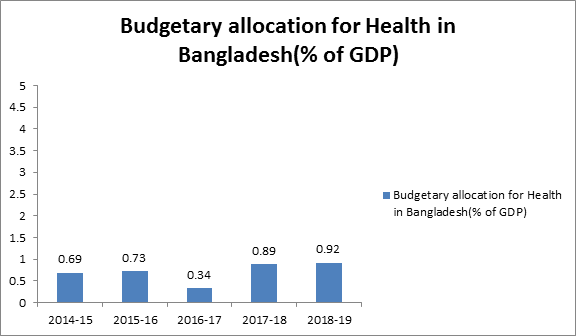

Figure 2: Budgetary allocation for health in Bangladesh (% of GDP)

Source: Centre for policy Dialogue (2018) [21]

World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that a country has to allocate at least 5 percent for healthcare to ensure equal access of all citizens [10]. But Bangladesh government has not allocated yet more than 1 percent in the proportion of GDP. In figure 2, allocations for healthcare are below 1 percent of GDP in the last five years. In 2014-15, the budgetary allocation for healthcare was 0.69 percent of GDP. After five years, the allocation is still below 1 percent of GDP which is 0.92 percent (2018-19).

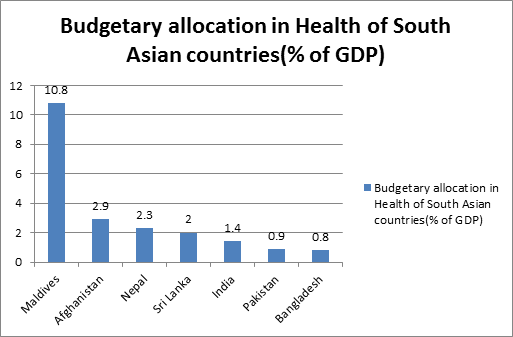

Figure 3: Budgetary allocation in Health of South Asian countries (% of GDP).

Source: UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and pacific (2018) [22]

Figure 3 shows that health expenditure in percentage of total GDP in South Asian countries. Bangladesh has the lowest allocation for the health of GDP among some other South Asian countries. In figure 3, it is observed that Maldives hold the top position in their budgetary allocation for health expenditure in the proportion of total GDP which is 10.8 percent. Afghanistan has held the second highest position in budgetary allocation for health in the percentage of total GDP among South Asian countries which 2.9 percent. Sri Lanka, India, and Pakistan have allocated a slightly higher percentage than Bangladesh.

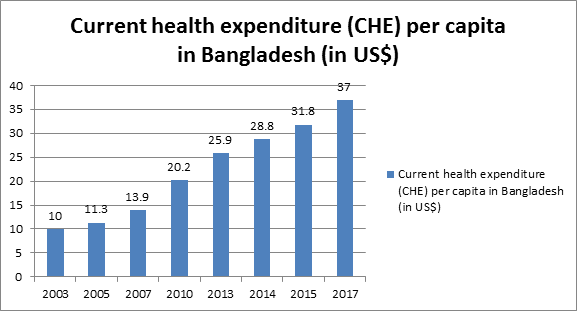

Figure 4: Current health expenditure (CHE) per capita in Bangladesh (in US$)

Budget allocation for per capita expenditure in public health is very low in Bangladesh. In 2017, per capita health expenditure of Bangladesh was $37 which is only one-third of what WHO recommended $85-$112 [23 & 24]. Health expenditure per capita is increasing and accessibility to health care system but it is decreasing due to low budget allocation and poverty respectively. According to figure 4, in 2003, current public expenditure per capita in Bangladesh was US$10. In 2010, the allocation was increased to $20.2. In 2017, the current health expenditure per capita has increased to $37 but the rate is not enough proportionally with the increasing rate of population and the price of medical equipment.

Table 2: Per capita health spending (in USD)

| Country | per capita health spending (in USD) |

| Bangladesh | $32 |

| India | $63 |

| Indonesia | $111.8 |

| Malaysia | $385.6 |

| Maldives | $943.9 |

| Nepal | $39 |

Source: WHO (2015) [25]

Table 2 shows the per capita health expenditure in neighboring countries. Bangladesh’s per capita health expenditure is $31.8, which is the lowest in the region compared to India, Nepal, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Maldives. In Malaysia, per capita health expenditure is more than twelve times comparing with Bangladesh. Besides, Maldives is around thirty times higher rather than Bangladesh and nearest India has double per capita health expenditure than Bangladesh.

Impacts:

Increasing Out-Pocket-Expenditures (OOPs)

Out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) are defined as direct payments made by individuals to health care providers at the time of service use. This excludes any prepayment for health services, for example in the form of taxes or specific insurance premiums or contributions and, where possible, net of any reimbursements to the individual who made the payments [26]. Health expenditures in a country consist of various sources like government expenditures, household Out-Pocket-Expenditures (OOPs), Voluntary Health Care Payment Scheme and others. Sources of Total Health Expenditures (THE) are interrelated with each other and if one of these sources decrease its expenditures then the others will increase it. If these sources of expenditures do not cooperate with each other, then country’s overall THE would be decreased. In the year 2015, Bangladesh’s sources of THE includes 71.8% of OOP expenditures, 17% government expenditures and 12% other financing sources e.g. NGOs health schemes [26]. It is quite obvious that government expenditure on health care is not enough and OOPs expenditure is too high for a country like Bangladesh where 24% of the population is still below the poverty line [7]. The problem is that government expenditure on health care is decreasing over time in the share of GDP and budget disbursements. As a result, other sources of THE financing are bearing the burden of decreasing government expenditures in healthcare.

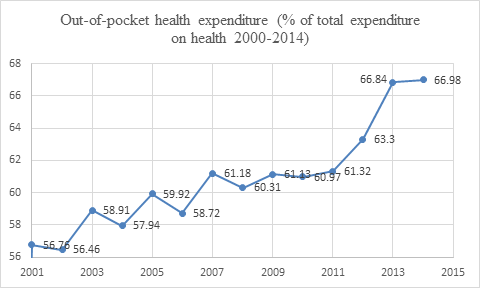

Figure 5: Out-of-pocket health expenditure (% of total expenditure on health 2000-2014)

Source: IndexMundi, 2018 [27]

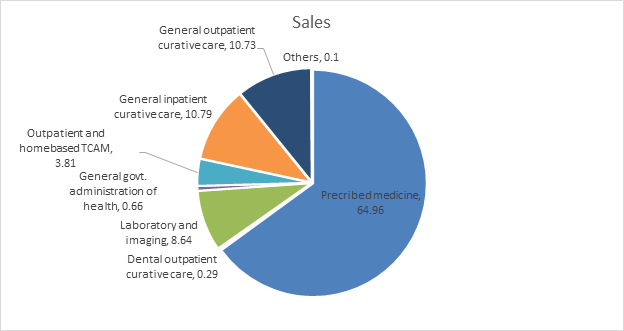

OOP increased dramatically as governments expenditures in THE decreased since 2001. As figure 5 shows, in 2001 OOP in THE was 56.76% and in 2014 the rate increased to 66.98% with a sharp increase from 2011-2014. During this period financing from other sources increased only little consisting of around 10% of total THE. THE includes various kinds of expenditures and most common of them are prescribed medicines which gets the lion share of 64%, also, general inpatient medical care 10%, general outpatient curative service 10 %, and others constitute 15% of THE.

Figure 6: Distribution of OOP by of services, 2012.

Sources: Bangladesh National Health Accounts, 2012 [28]

Burden on poor

‘’Impact of economic growth depends much on how the fruits of economic growth are used’’ Amartya Sen.

Ensuring universal healthcare is taken for granted in some countries whereas in Bangladesh; the opposition is true. The share of health care and social security is decreasing in the national budget even though GDP along with the economic success of Bangladesh is increasing each consecutive year. Bangladesh’s neighbor countries that are known as The Asian Tigers spend much of their GDP on education and health system along with industrial sectors and which is why they have become a stark example for developing countries.

Increasing OOPs has become a great concern for Bangladesh, particularly for poor people. Though population with higher income has managed to pay the health cost, poor people are bearing the burden with the high toll. Households have to pay for their own health care services since the government is withdrawing from providing healthcare services. Bangladesh is still a middle-income country with a huge population living under the poverty line. This large health care cost is enough to discourage poor people from using health care services which are damage their health further because of the negligence. Large expenditures in health services have decreased their consumption of other commodities like food and shelter. Sudden exposure to severe disease often makes poor people susceptible to vulnerability, increasing debt and often unemployment. Economically vulnerable people often have no options without selling their assets (e.g. land, house) because of serious diseases like cancer which pushes them further to the poverty threshold.

Poor Healthcare infrastructure

Bangladesh has lacked proper healthcare infrastructures since most of THE goes to consumption of drugs and other disease-related commodities. Public expenditure and infrastructural development are mostly built by the government because they are mainly done as social welfare in which the private sector is not interested. In Bangladesh, for each 1000 population, only 0.6 hospital bed is available [29]. Though the number of beds increased in past few years, it is still not enough as World Bank shows an increase of only 5 beds in 15 years and surely Bangladesh has achieved more economic growth compared to that.

Table 3: Hospital beds (per 10,000 populations)

| Year | Hospital beds (per 10,000 population) |

| 2015 | 8 |

| 2014 | 6 |

| 2005 | 3 |

Source: World Bank [13]

Decreasing budget on THE also has a much more severe impact on available physicians for the population. As the data indicates the available physicians are only 3 per 10,000 populations which is not enough for Bangladesh. Along with physicians, Bangladesh also faces a scarcity of nurses and midwives for this large population.

| Hospital beds (per 10,000 population)*/ Hospital beds (per 10,000 population) | 6/4 |

| HRH (physicians, nurses and midwives) density (per 10,000 population) | 5.8 |

| Density of physicians (per 10,000 population) | 3.0 |

| Density of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population) | 2.8 |

Source: Trading economics 2018 &WHO 2015 [29 & 13]

Lack of quality

As the former CEO of Apples used to say “Quality is more important than quantity. One home run is much better than two doubles”. From that point of view, Bangladesh has neither quality nor quantity in terms of public and private healthcare service. Public healthcare has scarcity of quality and quantity both compared to private hospitals. There are only 58 public hospitals in Bangladesh even though our number of districts is 64 [30]. Inferior quality of public hospitals was confirmed by a survey which claimed that public hospitals are inferior to private hospitals in terms of quality and private to foreign hospitals [31].

Foreign hospitals > private hospitals > public hospitals

Quality of public hospitals in Bangladesh is quite disappointing in terms hospital environment, doctors, nurses etc. and all of these problems has traced down to one culprit: decreasing rate of expenditures in public health sector. The problem is that hospitals are overpopulated and physicians are not capable of providing services to all those people.

Death rate from Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), also known as chronic diseases, tend to be of long duration and are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behaviors factors and the main types of NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (like heart attacks and stroke), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma) and diabetes [26]. Decreasing attention to healthcare creates various problems and increasing death rate by non-communicable diseases is one of them. There is a direct relationship between government expenditures and NCDs which is quite clear from observing the trend of government expenditures rate and the death rate from NDCs in past few years. Providing Public Health care services are important especially not only for public health but also for a country’s economic growth. Research shows that every 1 US$ spend to combat NCDs, there will be a 7 US$ return to society by a growth of employment, productivity and longevity of life [26].Though Bangladesh has attempted a few policies to reduce NCDs but the lack of implementation and monitoring of policies is still there as always [32].

Table 4: Death rate from non-communicable disease (percentage)

| Year | Death rate from non-communicable disease (percentage) |

| 2000 | 42.6 |

| 2010 | 58.3 |

| 2015 | 65.4 |

| 2016 | 66.9 |

Source: World Bank, 2017 [14]

As, NCDs related death is increasing in Bangladesh as the table 4 shows that Government has not paid proper attention to the health sector as a whole let alone NCDs especially. In 2000 the death rate from NCDs was 42.6% which increased to 58.3 and in 2016 it stood up to 66.9%. Currently more than half of the deaths in Bangladesh are occurred due to NCDs which is an increase of 24.3% in 15 years.

Conclusion:

Health is fundamental element for human development and providing healthcare service to everyone is a constitutional obligation of the Bangladesh government. Bangladesh is committed to provide universal health coverage to all but government has failed to perform this task. Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a basic right that means every person everywhere should have access to quality healthcare service without suffering financial hardship. Although Bangladesh has achieved the MDG goals in reducing child mortality and maternal mortality but universal healthcare services for everyone is yet to be established. Budgetary allocation for health sector always remained around 5 percent of total budget which is not enough for Bangladesh. As consequences, a large number of people are out of health service coverage and the out of pocket expenditure (OOP) per household is increasing. Due to high rate of OOP, poor people have less accessibility in healthcare services which is increasing inequality in society. The study shows that the budget allocation of public health sector is very low in proportion to GDP in Bangladesh. As a result, scarcity of budget in public health sector is causing increasing per capita out-of-pocket expenditure. Around 67 percent of total expenditure in healthcare is out-of-pocket expenditure in Bangladesh which is the highest among south-Asian countries. Besides, High expenditure in health sector is become a burden for poor people, decrease public healthcare services quality and also decreases infrastructural quality of health care. Government intervention in health sector might be able to reduce health related problems like increasing NCDs which will contribute further to economic growth.

Reference:

- MANNAN M.A.(2013). “Access to Public Health Facilities inBangladesh: A Study on FacilityUtilisation and Burden of Treatment”. Bangladesh Development Studies, XXXVI (4).

- Ahmed SM, et al. (2013). “Harnessing pluralism for better health in Bangladesh”. The Lancet, 382(9906), 1746-55. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 (13)62147-9

- Chowdhury AMR, et al. (2013). “The Bangladesh paradox: exceptional health achievement despite economic poverty”. The Lancet. 382(9906), 1734-45. Retrieved from: http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 (13)62148-0.

- Balabanova D, et al. (2013). “Good Health at Low Cost 25 years on: lessons for the future of health systems strengthening”. The Lancet, 381(9883):2118-33. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62000-5.

- The Millennium Development Goals Report New York: United Nations, 2015.

- RAHMAN SM, et al. (2005, December). “Poor People’s Access to Health Services in Bangladesh: Focusing on the Issues of Inequality”. Paper presented at Network of Asia-Pacific Schools and Institutes of Public Administration and Governance (NAPSIPAG) Annual Conference 2005, Beijing, PRC, 5-7.

- BBS.2016. Statistical Year Book. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Bangladesh.

- Tobin J. (1970). “On limiting the domain of inequality”. The Journal of Law and Economics.13 (2), 263–77.

- Sen A. (2002). “Why health equity?” Health Econ. 11(8),659–66.

- Annual Financial Statement (Budget) Bangladesh: Ministry of Finance, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. [Cited July, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mof.gov.bd/en/

- Budget Speech, 2018-19: Ministry of Finance, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; 2018-19.

- World Bank. 2017. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure), Bangladesh 2017. World Bank.

- World Bank. 2016. Hospital beds (per 1000 population), Bangladesh. World Bank.

- World Bank. 2017. Death rate of unaffected diseases (%), Bangladesh 2017. World Bank.

- Ferdous, AO. (2008). “Health Policy Programmes and System in Bangladesh: Achievements and Challenges”. South Asian Survey, 263-288.

- Islam, A. et al. (2015). “Health System Financing in Bangladesh: A Situation Analysis”. American Journal Of Economics, Finance And Management, 1(5), 494-502. Retrieved from: http://files.aiscience.org/journal/article/html/70200056.html.

- Peters, D. et al. (2008). “Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 161-171. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.011

- Hassan M, et al. (2016). Healthcare Financing in Bangladesh: Challenges and Recommendations. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science, 15(4), 505. doi: 10.3329/bjms.v15i4.21698

- Molla, A. & Chi, C. (2017). “Who pays for healthcare in Bangladesh? An analysis of progressivity in health systems financing”. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0654-3.

- International Relations and Security Network, Primary Resources in International Affairs (1972). Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- National Budget analysis 2018-2019. (2018). Centre for Policy Dialogue. https://cpd.org.bd>category > national budget analysis.

- Budget allocations for health, education continue to shrink. (2018, June 29). Dhaka Tribune.

- World Bank. 2017. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure), Bangladesh 2017. World Bank.

- Nahar, K. (2017, December 16). “BD spends one third of what recommend”. The Financial Express.

- World Bank (2015). “Health expenditure, per capita (current US$)”. The World Bank.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Health financing profile 2017 Bangladesh [Data file]. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259640/BAN_HFP.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Index Mundi. (2015). Bangladesh – Out-of-pocket health expenditure (% of total expenditure on health) [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/bangladesh/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.TO.ZS

- Bangladesh National Health Accounts Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2012.

- Trading Economics. (2012). Bangladesh – Hospital beds. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/bangladesh/hospital-beds-per-1-000-people-wb-data.html

- BBS.2017. Statistical Year Book. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Bangladesh.

- Siddiqui, N., &Khandaker, S. A. (2007). “Comparison of Services of Public, Private and Foreign Hospitals from the Perspective of Bangladeshi Patients”. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 25(2), 221–230.

- Biswas T, et al. (2017). “Bangladesh policy on prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: a policy analysis”. BMC Public Health, 17(1). doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4494-2

- Garrett L, et al. (2009). “All for universal health coverage”. The Lancet. 374(9697), 1294-9. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 (09)61503-8

need this file

Hello,

Could you please send me this paper? I need this as a reference for my thesis.

Thanks.

Shiny