“There was a red cloud in the sky the other morning,” says Pemba Bhuti Sherpa, a yak herder in the Himalayan village of Walung in the Taplejung District of north-eastern Nepal. “It might snow tomorrow”.

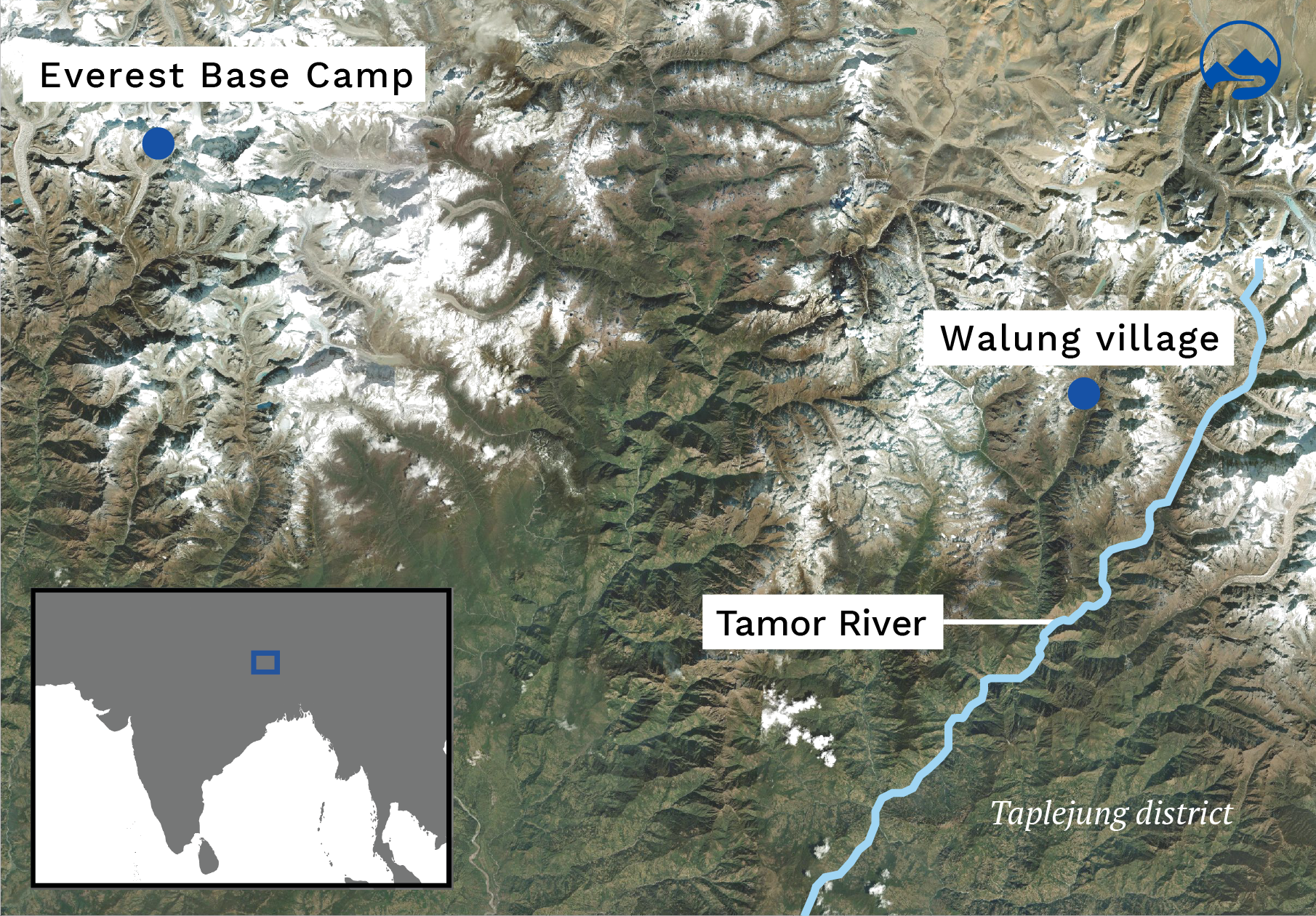

Speaking in November 2021, she has a vested interest in foreseeing the snow’s arrival: her herd is scattered across the upper reaches of the Tamor Valley, in which Walung is situated, and if the animals aren’t brought down before the heavens open, she’ll be cut off from them. If the grass is buried under a thick blanket of snow, the yaks could starve without supplementary fodder. Considering the sky’s signal, Pemba collects the animals in anticipation.

But when the next day arrives, the snow does not.

When snow finally comes, on December 29, it comes all at once. Three feet fall within hours – one foot for each month the snowfall has been delayed. When Pemba was a child, the first snows used to fall in September.

After one roof collapses under the groaning weight of snow, the other villagers take to their rooftops to shift the drifts. This ritual used to happen six or seven times in a winter. But these days, with the village experiencing less snowfall than in the past, it is rarely necessary.

The toll of erratic snowfall

This unanticipated blizzard is a blow for herders. Until the day before, the weather had been clear, showing none of the traditional indicators of snowfall, such as the guzig: wispy ropes of cloud draped between the stars. The yak were roaming freely across the valley when they were suddenly stranded by snowdrifts. Beyond the reach of herders, six or seven yak perish in the hills from starvation or avalanches, representing a loss of 960,000 Nepalese rupees (nearly 8,000 US dollars) for their distraught owners.

Yak herders are no longer able to depend on their traditional knowledge for forecasting weather

Tashi Dorji, ICIMOD

These events are grimly familiar to Pemba. After similarly unpredictable and disruptive snowfall two years ago, she lost half of her 90-strong herd, incurring losses worth tens of thousands of US dollars, she says.

Tashi Dorji, who heads the conservation programme the Kanchenjunga Landscape Initiative at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Kathmandu, confirms that this tale is far from unique to Walung. This winter, he says, over a hundred yaks died in Bhutan due to unusually heavy snows; the fatalities topped 300 in northern Sikkim. While vegetation changes, disease, and water scarcity have all taken their toll in the eastern Himalayas, erratic snowfalls can be the final death knell for valuable livestock.

“Yak herders are no longer able to depend on their traditional knowledge for forecasting weather,” says Dorji. “The biophysical and astronomical indicators used for generations to make those predictions have vanished with climate change.”

In the Himalayas, climate change is taking place faster than in almost any other region on the planet. This trend is set to continue: even if average global temperature increases are limited to 1.5°C, the Himalayas are predicted to warm at least a further 0.3°C. As highly ecologically sensitive zones, the profound impacts already wreaked across high mountain environments by even small degrees of warming have been no surprise for climate scientists. But for many Walung residents, the cause of these environmental changes is unequivocal: it signifies the arrival of kawa nyampa – the bad times.

Climate change as divine revenge

Across Buddhist areas of the Himalayas, it is widely believed that the landscape is animated by a host of local deities and spirits. When they are angered by human activities, a common form of retaliation is severe weather. This has been termed ‘the Tibetan moral climate’ by anthropologists Toni Huber and Poul Pedersen, in which the weather mimics the character of human communities.

Similar beliefs are shared by several indigenous communities in the Arctic and Pacific Islands. As floods batter communities in Nepal, and seas consume the sands of Polynesia, the consequences of decades of unfettered greenhouse gas emissions have left some of the most vulnerable communities in the world wondering how they’ve angered their gods – or displacing the blame onto friends and neighbours within their own villages.

The residents of Walung interviewed for this article say it is declining religious belief which prompts the societal and environmental breakdown attributed to kawa nyampa. When the blizzard arrives, many burn an offering of tea, butter and incense called jhasumasu to protect their animals. But others worry that such external actions cannot mend the ‘broken’ climate, as inner characters are to blame.

Feeding the fire in a house plunged into shadow by midday power outages, 58-year-old widow Yangchen Sherpa says that the climatic changes of the recent past must be a sure sign of kawa nyampa. “I don’t know how to explain it. In the past, we used to have snowfall at the right time, rainfall at the right time, and the sky would be clear.” Today, she says, “we hardly have snowfall, and there’s too much rain. You can barely see snow these days.” She is silent for a long moment, before speaking again: “The times have changed, and man has changed. All the good men are dead.”

Beneficial changes a bad omen

For Walung residents, climate change does not always feel like a catastrophe. While Himalayan biodiversity is declining at a staggering pace, threatening the viability of entire ecosystems, the human costs do not always manifest immediately.

One herder confides: “In some ways, climate change makes our lives easier. Without the large snowfalls of the past, we can watch the [domestic] animals more easily.” A warmer climate also reduces fodder costs, as when there is no snow on the ground, the animals can be left to graze wild vegetation.

Traders, selling everything from rugs to yaks, also report welcome changes – the border pass with Tibet, Tipta, which sits at an altitude of 5,136 metres and was previously blocked by snow for much of the winter, is now accessible year-round.

Yet, universally, residents of Walung agree that these environmental changes remain a bad omen. What they leave is a sense of unease; the sense that the knowable world is slipping away.

As the snowfall has become unreliable, residents complain that people’s characters cannot be depended upon as they could in the past. With conflict and declining morals viewed as a key cause of kawa nyampa, many denounce their local community as the cause of the climatic changes they have noticed.

“Everyone has become politically divided,” complains Tamding Gyalpa Sherpa. “People say to each other, ‘you support [the Nepali political party] Congress, you support CPN [Nepal Communist Party]’. This has caused the bad weather in Walung.”

Faith in good people persists

65-year-old retired trader Dorjee Bara remembers the devastating glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) that occurred during his childhood in Walung. An increasingly common disaster in the Himalayas, GLOFs – which occur when meltwater breaches the natural dams that contain glacial lakes – have become a potent symbol of climate change in the region.

Yet while Dorjee has observed extensive environmental changes in his lifetime, he is optimistic about future risks. The glacial lake that caused the earlier outburst in Walung has shrunk in recent years, as the formerly snow-covered mountainside has gradually transformed to naked rock. Many in Walung consider this a sign that the threat of GLOFs in the area has receded – although scientists warn that the risk across the Himalayas overall is rising.

Drawing on the Buddhist principle of karma, Dorjee believes that negative behaviour can bring on environmental calamities. But faith in his community – people described as “good people with good hearts” – reassures him that the valley may be safe, for now. A cautionary note enters his voice. “The responsibility for disasters lies with us,” he warns. “If we do bad things, and [a disaster] happens, I cannot blame the Earth, I cannot blame the Dalai Lama. It will be us.”