By James M. Dorsey

The hacked email account of Yousef al-Otaiba, the influential United Arab Emirates ambassador in Washington, has provided unprecedented insight into the length to which the small Gulf state is willing to go in the pursuit of its regional ambitions.

Mr. Al-Otaiba is unlikely to acknowledge the contribution the insight has made to understanding the ten week-old Gulf crisis and diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar that was engineered by the UAE. The ambassador may, however, have greater appreciation for the contribution his private email exchanges have made to the theory and policy debate about the place of small states in an increasingly polarized international order.

Similarly, Mr. Al-Otaiba is unlikely to see merit in the fact that his email exchanges raise serious questions, including the role and purpose of offset arrangements that constitute part of agreements on arms sales by major defense companies as well as the relationship between influential, independent policy and academic institutions and their donors.

To be sure, Mr. Al-Otaiba is likely to be most concerned about the potential damage to the UAE’s reputation and disclosure of the Gulf state’s secrets caused by the hack. No doubt, the selective and drip-feed leaking of the ambassador’s mails by Global Leaks, a mysterious group that uses a Russian email address, is designed to embarrass the UAE and support Qatar in its dispute with an alliance of nations led by the Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

Mr. Al-Otaiba as well as his interlocutors have not confirmed the authenticity of the mails. The UAE embassy did however tell The Hill that Hotmail address involved was that of the ambassador. Moreover, various of the leaks have been confirmed by multiple sources.

The UAE is hardly the only government that donates large sums to think tanks and academic institutions in a bid to enhance soft power; influence policy, particularly in Washington; and limit, independent and critical study and analysis. While Gulf states, with the UAE and Qatar in the lead, are among the largest financial contributors, donors also include European and Asian governments. Think tank executives have rejected allegations that the donations undermine their independence or persuade them to do their donor’s bidding.

The latest leaks, however, raise the debate about the funding of think tanks and academic institutions to a new level. Mails leaked to The Intercept, a muckraking online publication established by reporters who played a key role in publishing revelations by National Security Council whistle blower Edward Snowden, raise questions not only about funding of institutions, but also the nature and purpose of offset arrangements incorporated in arms deals. Those deals are intended to fuel economic development and job creation in purchasing countries and compensate them for using available funds for foreign arms acquisitions rather than the nurturing of an indigenous industry.

The mails disclosed by The Intercept as well as The Gulf Institute, a Washington-based dissident Saudi think tank, showed that a UAE donation of $20 million to the Washington-based Middle East Institute (MEI) involved funds funnelled through Tawazun, a Abu Dhabi-based investment company, and The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR) that is headed by UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, that had been paid to the UAE in cash rather than projects by defense contractors as part of agreements to supply military equipment.

The US embassy in Abu Dhabi reported as far back as 2008 in a cable to the State Department published by Wikileaks that “reports as well as anecdotal evidence” suggested that “that defense contractors can sometimes satisfy their offset obligations through an up-front, lump-sum payment directly to the UAE Offsets Group” despite the fact that “the UAE’s offset program requires defense contractors that are awarded contracts valued at more than $10 million to establish commercially viable joint ventures with local business partners that yield profits equivalent to 60 percent of the contract value within a specified period (usually seven years).”

The cash arrangement raises questions about the integrity of offset arrangements as well as their purpose and use. In the case of MEI, it puts defense contractors in a position of funding third party efforts to influence US policy. In an email to Mr. Al-Otaiba, MEI president Wendy Chamberlain said the funding would allow the institute to “counter the more egregious misperceptions about the region, inform US government policy makers, and convene regional leaders for discreet dialogue on pressing issues.

The UAE has been a leader in rolling back achievements of the 2011 popular Arab revolts that toppled the leaders of four countries, promoting autocratic rule in the region, and opposing opposition forces, particularly the controversial Muslim Brotherhood.

The donations by countries like the UAE and Qatar to multiple think tanks as well as the source of the funding links to the even larger issue of strategies adopted by small states to defend their independence and ensure their survival in a world in which power is more defuse and long-standing alliances are called into question.

The leaked emails provide insight into the UAE’s strategy that is based on being a power behind the throne. It is a strategy that may be uniquely Emirati and difficult to emulate by other small states, but that suggests that given resources small states have a significant ability to punch above their weight.

US intelligence officials concluded that the hacking of Qatari news websites to plant a false news report that sparked the Gulf crisis in early June had been engineered by the UAE. The UAE move was embedded in a far broader strategy of shaping the Middle East and North Africa in its mould by turning Saudi Arabia into its policy instrument.

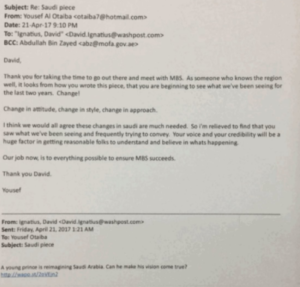

Leaked email traffic between Mr. Al Otaiba and three former US officials, Martin Indyk, who served in the Clinton and Obama administrations, Stephen Hadley, former President George W. Bush’s national security advisor, and Elliott Abrams who advised Presidents Bush and Ronald Reagan, as well as with Washington Post columnist David Ignatius documents what some analysts long believed but could not categorically prove. It also provided insight into the less than idyllic relationship between the UAE and Saudi Arabia that potentially could become problematic.

In the emails, Mr. Al-Otaiba, who promoted Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Washington as Saudi Arabia’s future since he came to office in 2015, was unequivocal about UAE backing of the likely future king as an agent of change who would adopt policies advocated by the UAE.

“I think MBS is far more pragmatic than what we hear is Saudi public positions,” Mr. Al-Otaiba said in one of the mails, referring to Prince Mohammed by his initials. I don’t think we’ll ever see a more pragmatic leader in that country. Which is why engaging with them is so important and will yield the most results we can ever get out of Saudi,” the ambassador said. “Change in attitude, change in style, change in approach,” Mr. Al-Otaiba wrote to Mr. Ignatius.

In another email, Mr. Al-Otaiba noted that now was the time when the Emiratis could get “the most results we can ever get out of Saudi.”

In a subsequent email dump, published by Middle East Eye, an online news site allegedly funded by persons close to Qatar, if not Qatar itself, and also sent to this writer, Mr. Al-Otaiba, makes no bones about his disdain for Saudi Arabia and his perception of the history of Emirati-Saudi relations.

Writing to his wife, Abeer Shoukry, in 2008, Mr. Al-Otaiba describes the Saudi leadership as “f***in’ coo coo!” after the kingdom’s religious police banned red roses on Valentine’s Day. The powers of the police have been significantly curtailed since the rise of Prince Mohammed, who has taken steps to loosen the country’s tight social and moral controls.

In one email, Mr. Al-Otaiba asserts that Abu Dhabi has battled Saudi Arabia over its adherence to Wahhabism, a literal, intolerant and supremacist interpretation of Islam, for the past 200 years. The ambassador asserted that the Emirates had a more “bad history” with Saudi Arabia than anyone else.

Taken together, the leaked emails involving multiple other issues, including the UAE’s military relationship with North Korea as well as its competition with Qatar to host an office of the Afghan Taliban, serve not only as a source for understanding the dynamics of the Gulf crisis, but also as case studies for the development of more stringent guidelines for funding of policy and academic research; greater transparency of military sales and their offset arrangements; and the place of small states in the international order as well as the factors that determine their ability to maintain the independence and at times punch above their weight.

To be sure, that was not the primary purpose of the leaks. The leaks were designed to further Qatar’s cause and undermine the UAE’s arguments as well as embarrass it. The jury is still out on the degree to which the leakers may have succeeded. Nonetheless, one unintended consequence of the leaks is that they raise issues that go to the core of a broad swath of issues, including accountability, transparency, economic and social development, and international relations.