The Indus — Sindhu, Abasin, Mehran — is much more than just a river. It is a timeless bond that connects the heart of Pakistan, stretching from the chilly mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan to the warm, sunlit shores of Sindh. Over the centuries, the Indus has supported a beautiful blend of cultures, languages, and communities — a river that doesn’t just flow, but nurtures, loves, and shapes the lives it touches.

However, this ancient lifeline now stands at a critical juncture. On April 24, 2025, India’s unprecedented suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty dismantled a fragile framework of cooperation, plunging Pakistan’s water future into deep uncertainty. Climate change, relentless glacier melt in the Himalayas, and ambitious yet ecologically risky domestic projects like the Green Pakistan Initiative (GPI) and the Cholistan Canal compound the river’s growing anguish.

At this crossroads, Pakistan must revive its sacred connection with the Indus — recognizing it not as a mere resource, but as a living, loving force that embodies our shared past, present, and future.

The Indus: More Than a River

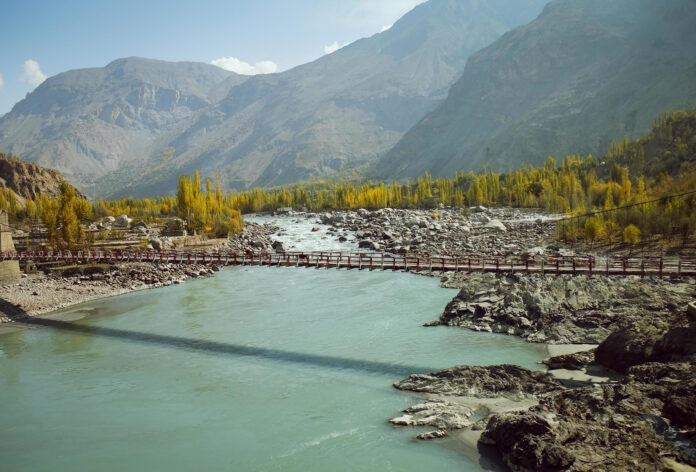

The Indus is not confined by geography; it exists in the languages, customs, and hearts of those who dwell along its mighty course. In Gilgit-Baltistan, it is revered as Abasin, “the Father of Rivers,” where communities speaking Shina, Balti, and Burushaski have lived in harmony with its icy embrace for centuries.

As the river flows southward, it kisses the lands of Kohistan, Hazara, and the vast plains of Punjab, nourishing communities speaking Hindko, Pashto, Punjabi, and Seraiki. In Sindh, it is tenderly called Mehran, the river’s name in the hearts of Sindhi-speaking people, becoming the wellspring of their identity, poetry, and song.

Every bend of the Indus carries a unique story — of prayer flags fluttering in Skardu, of sufi qawwals echoing in Sehwan Sharif, of fishermen casting their nets under the twilight skies of Thatta. The Indus is the first storyteller of Pakistan — an unbroken witness to thousands of years of human dreams, struggles, and celebrations.

The Cradle of Ancient Civilizations

Long before borders were drawn, the banks of the Indus were home to one of humanity’s earliest urban wonders: the Indus Valley Civilization. Cities like Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, and Dholavira bore witness to the heights of human creativity, governance, and spirituality. Here, people mastered urban planning, traded with distant lands, and lived by the rhythms of the river. Even the name “India” derives from Sindhu, a testament to the river’s foundational role in shaping South Asian identity.

Yet history offers cautionary tales. The disappearance of the Sarasvati River — often linked with climatic shifts and tectonic changes — led to the decline of once-mighty settlements. Today, echoes of that ancient sorrow warn us: when rivers die, civilizations falter.

Mehran and the Life of Sindh

Nowhere is the Indus more intimately beloved than in Sindh, where it is tenderly called Mehran, meaning “the benevolent.” Here, the river softens harsh climates, quenches vast farmlands, and breathes life into folklore, music, and identity.

The river also shapes the economy, replenishing the rice paddies, cotton fields, and mango orchards that are the pride of Sindh. It sustains the magnificent Indus Delta — a fragile web of mangroves, estuaries, and mudflats that provide homes to countless species, from the endangered Indus River dolphin to the migratory flamingos that grace the skies every winter.

The bond with the Indus is foundational to Sindhi life. It shapes worldviews, agricultural practices, and spiritual customs, ensuring that communities remain interconnected not only with the river but also with one another.

The Indus Delta: An Ecological and Economic Lifeline

As the Indus nears its final stretch, it forms the Indus Delta—locally known as Lar. This delta, spanning thousands of square kilometers in southern Sindh, is an ecological treasure. It includes wetlands, mangrove forests, mudflats, and estuaries, all teeming with biodiversity. These ecosystems act as vital buffers, protecting the land from the harshness of climate extremes.

The delta is also home to numerous fishing communities in towns like Kharo Chan, Jati, Sujawal, Thatta, Bajo, and several others. Fishing and small-scale agriculture form the backbone of their economy, sustained by the seasonal abundance provided by the Indus. However, these habitats now face serious threats due to reduced freshwater flow, rising salinity, and unregulated development.

The delta serves essential ecological functions: it recharges aquifers, nourishes agricultural lands, and supports vital mangrove forests that stabilize the coastline against storms and erosion. Moreover, the region is home to endangered species, such as the Indus River dolphin and Hilsa shad, which depend on a healthy river system. Unfortunately, these species are now at risk due to the declining health of the river.

Environmental Degradation: A Looming Crisis

But the Indus today is a river in distress. Upstream diversions, over-extraction, and the impacts of climate change have weakened its flow. Traditional flood cycles that once nourished farms and wetlands are now disrupted. Salinity creeps inland, swallowing fertile land. The Indus Delta shrinks, mangroves vanish, and fishing communities from Thatta to Badin are left struggling. India’s unprecedented suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty has only deepened the crisis, threatening the very fabric of life that has depended on it for centuries.

Wisdom from the River’s People

The solution to saving the Indus lies not solely in engineering marvels or international treaties, but in listening — to the people who have lived by its side for generations.

Empowering local communities, incorporating their wisdom into national policies, and nurturing eco-consciousness are crucial steps. School curriculums, government programs, and conservation initiatives must be deeply rooted in cultural awareness and environmental stewardship.

For centuries, people on both sides of the river have thrived, nourished by the Indus, regardless of their cost, nationality, or religion. It is only in recent times that we have imposed boundaries, often focusing more on these divisions than on our connection to Mother Nature.

Eco-Conscious Tourism: A Pathway for Sustainable Livelihoods

A vibrant eco-tourism economy can rejuvenate the relationship between communities and the Indus. From the turquoise lakes of Attabad and Satpara in the north to the tranquil wetlands of Keenjhar and Haleji in the south, the Indus’s beauty offers rich opportunities for responsible tourism that celebrates nature, history, and culture. Storytelling tours, spiritual pilgrimages, and community-led heritage walks could help preserve both the economy and the environment.

Eco-tourism offers a promising avenue for linking environmental conservation with economic growth. Sindh’s natural landscapes, such as the serene lakes of Keenjhar, Haleji, and Manchar, as well as the coastal creeks of Keti Bunder, are rich in biodiversity and offer a wealth of opportunities for eco-friendly tourism.

By fostering community-led tourism initiatives — such as nature trails, heritage tours, and local guide networks — Sindh can generate sustainable income while preserving its environmental and cultural heritage. Storytelling tours led by elderly musicians and environmental activists can raise awareness about the Indus River’s significance and its contemporary challenges.

This vision of eco-tourism goes beyond borders. It is not just about one country; both India and Pakistan can benefit from the shared love and deep connection people on both sides of the river have for the Indus. By celebrating and preserving this river together, both nations can cultivate stronger bonds, fostering peace, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to protecting the Indus for future generations. The river, after all, flows through the hearts of both nations, uniting them in a common heritage.

Rekindling the Bond with Mehran

The Indus is not just a river; it is the lifeblood of our shared history, a sacred thread woven through the fabric of our lives, hearts, and souls. It carries the whispers of our ancestors and the dreams of our descendants. To preserve the Indus is to preserve the essence of who we are — a people united by more than mere geography, but by a deep and eternal connection to the land, to nature, and to one another.

As we stand at the crossroads of history, we must remember that the true strength of nations lies not in borders, but in the bonds that unite them. The Indus has been a symbol of life and unity long before lines were drawn across the map. Now, in our time of crisis, it calls to us once more — not as a resource to be exploited, but as a mother to be cherished, a river that sustains us all, regardless of where we stand.

Let us rise to the call of the Indus, with hearts full of love, minds filled with wisdom, and hands united in action. Let us restore its flow, not only for ourselves but for the generations that will inherit this sacred river. Together, across borders, across cultures, let us walk in the footsteps of our ancestors, who knew that when rivers thrive, civilizations flourish. Let the Indus live, not just as a river, but as a symbol of our shared destiny — a river of peace, of hope, and of boundless love for all who call its waters home.