The Vyasi Hydroelectric Project will soon start to generate electricity in Uttarakhand in northern India. This 120-megawatt station is part of the 420 MW Lakhwar-Vyasi project, the biggest hydroelectric dam complex on the Yamuna River. Work on the next phase, the 300 MW Lakhwar project 5 kilometres upstream of the Vyasi dam, is due to begin this year.

Conceptualised nearly half a century ago, the project ground to a halt in 1992. It was controversially revived in 2014 based on old clearances. There has been no environmental impact assessment, local consultation, or disaster risk study.

In the last week of December, one of the two turbines at the Vyasi dam was tested, according to Yashpal Tomar, a member of the Yamuna Sanitation Committee (a local civil society organisation). The water level of the Yamuna fell dramatically on the 29th, two days before the turbine was tested.

“People were afraid that the Yamuna had dried up completely. The fish came to the surface as the water receded,” says Tomar, describing onlookers “hitting the fish with sticks and some with stones, as they flopped around” so they could take them to eat or sell. “It was a very heartbreaking scene,” he says, his voice trembling.

He adds: “We spoke to the local administration and Uttarakhand Jal Vidyut Nigam [UJVN, the Uttarakhand state-owned corporation in charge of energy] officials to release water in the Yamuna… or else the fish will die.” Pictures were shared with officials in the morning of the 29th, and some water was released in the afternoon. If water is not released properly, he says, “There will be no river for the 5 kilometres between the Vyasi Dam and the power house.” This is the stretch of the river that is diverted through a tunnel. The straight length of the tunnel is 2.7 km, but it affects a 5 km section of the winding river.

From December 2021, a 5 sq km reservoir lake for the Vyasi dam started to be filled. As of 11 January this year, the water level was 621 metres. The maximum is 631 metres and the base level is 590 metres; it is the kinetic energy created in this 40 metres of difference that will drive the turbines. From February, both Vyasi’s turbines will be ready to generate electricity. Only a little work on transmission lines is left, which is due to be completed by the end of January.

“We are just waiting for the people of Lohari village to leave,” said an official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The village waiting to drown

The Vyasi project will affect 334 families and six villages. One of them is Lohari, home to indigenous communities of Uttarakhand’s Jaunsar-Bawar region. This entire village of 72 families will be swallowed by the lake, yet its residents are refusing to leave as they are unwilling to accept the compensation being offered for their land.

When The Third Pole visits Lohari in the second week of January 2022, women from the village show the water rising towards the village. Mango trees are underwater, a bridge has fallen into the lake and the cattle shed has been cut off from the village. Some of the watermills have been submerged, and the cremation ground is completely flooded.

The women also point to a yellow marker on a rock signifying 626 metres. At this point their farms will be submerged; at 631 metres, the rest of the village will be lost. Beautiful two-storey houses built in traditional mountain styles will disappear into the lake. An entire culture will drown.

Lohari villagers demand land in exchange for land

Gullo Devi, who is about 70 years old, says: “The lake has reached our village. The government says, ‘Take the money and give us your land.’ Our demand is that we need land in lieu of the land we are giving up, not money.”

Another villager, Chanda Chauhan, adds: “We are giving the property of our ancestors to the government. Our fields, which grow wheat, maize, ginger, chilli, onion, garlic, turmeric and pulses, are drowning. Where will we farm?”

Lohari will be affected by the Lakhwar as well as Vyasi project. In 1972, a land acquisition agreement was signed between the government and the villagers for the dam complex. Between 1977 and 1989, 8,495 hectares of land in the village was acquired. About 9 hectares of land is yet to be acquired for the Lakhwar project.

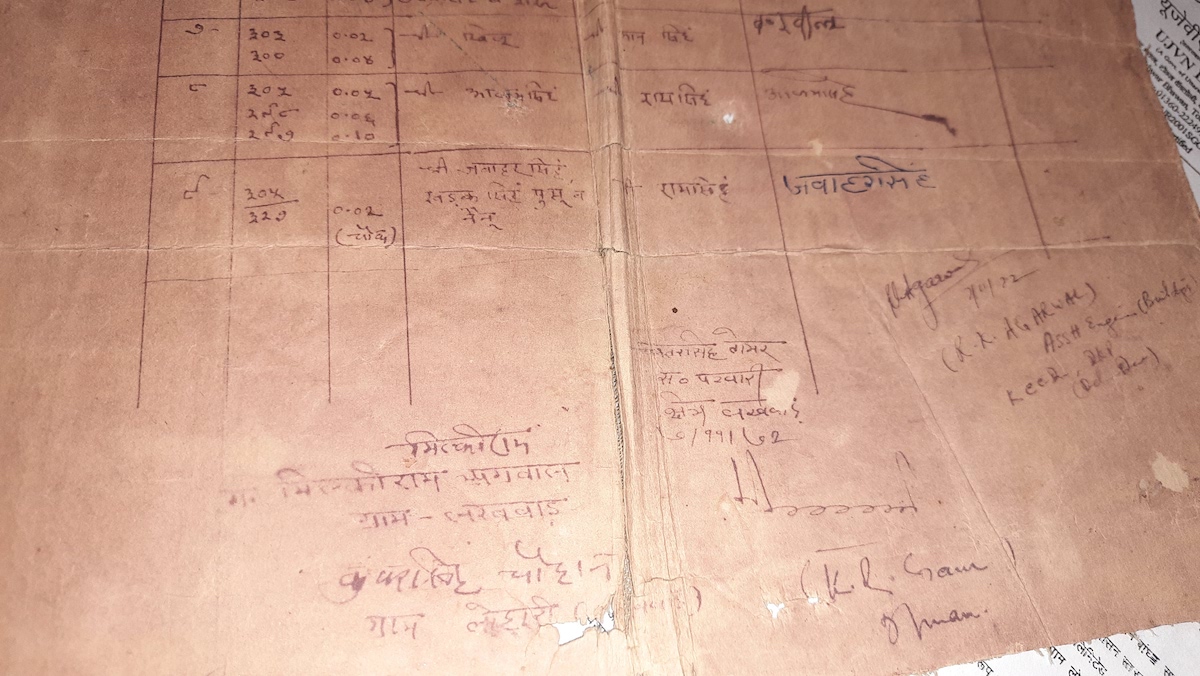

Dinesh Singh Tomar, secretary of a committee formed by Lohari villagers to negotiate with the authorities on compensation, shows The Third Pole the documents from the 1972 agreement. The agreement specifies that in future, land is to be given in compensation for land acquired under the project.

But in a cabinet meeting in July 2021, the Uttarakhand government backed away from this. There was speculation that this was because any such allocation would lead to a flood of demands from other villages, which the government would not be able to fulfil.

In 2017 the government offered a payment to Lohari villagers that would bridge the difference between how much their predecessors were paid in 1972 and the land rates currently. This offer was refused. The villagers also refused to take part in assessments valuing their properties, so officials took measurements from outside their houses to estimate the compensation to be paid.

How will we take care of the little land left over when we are removed from here?

Suchita Tomar, ASHA worker in Lohari village

Suchita Tomar is an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA, a community health worker) assigned to Lohari village. She says: “Land is being acquired piecemeal, while compensation is given in chunks. Some land was acquired in 1972, some now, and then some land will be taken as the project commences. We say take the land in one go. How will we take care of the little land left over when we are removed from here?”

The villagers also say that it is not possible to buy replacement farmland and build new homes with the money the government is giving. Therefore, for four months last year, from 5 June to 2 October, the people of Lohari staged a dharna (sit-in protest), demanding rehabilitation and land in compensation for land.

Villager Rajendra Singh Tomar says: “It was time to work in our fields. But we kept the demonstration going with our children. On 2 October, at 4am the police came and put us in the Dehradun [the capital of Uttarakhand] jail. After five days, we got bail from the High Court. We were protesting for our motherland. We are tribal people. The law also says that scheduled castes and scheduled tribes will be given land in compensation of land [if acquired for irrigation projects].”

Disasters and the Vyasi dam

With no comprehensive impact assessment, and no scientific studies on the impact of the dam, the only knowledge of how it is affecting the fragile geography of the region is a series of disasters.

As The Third Pole’s correspondent travelled the 66 km from Dehradun through Vikasnagar to Lohari in the first and second week of January 2022, they passed a number of landslides. About 400 metres before a tunnel built for the project, there was so much debris on the road that it was impossible for vehicles to pass.

In response, the Yamuna Sanitation Committees have been formed in the valley. In Vikasnagar, the vice-chair of the committee, Praveen Tomar, shows The Third Pole the storm drain joining the Yamuna. “After a landslide in August last year, 10 feet of debris flowed down the drain. The elders say that they have never seen so much debris in this drain. Our watermill sank completely. Disasters are now coming in a more dire form than ever before.”

Bhim Singh Rawat, associate coordinator at NGO the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, monitors the incidence of heavy rainfall like cloudburst in Uttarakhand. He says that from 25-27 August, there was heavy rain across the state. There were at least seven cloudburst incidents in the Ganga-Yamuna basin in Dehradun.

The Vyasi project area was also affected. Rajeev Agarwal, executive director for the Vyasi project, told The Third Pole that the boundary wall of the powerhouse building was affected by the extreme weather but there was no damage inside.

Chanda Chauhan, from Lohari village, said: “All the mountains have become fragile due to these dams and power projects. Last year there was a cloudburst in Tapovan [a village in Chamoli district, Uttarakhand]. There was great devastation in the Kedarnath disaster. If this happens here, where will we go?” Around her other women from the village nodded in agreement.

Questions over necessity of Lakhwar-Vyasi project

Cultures were born on the banks of the Yamuna. Now, they are being destroyed so that electricity can be generated from the river’s waters, and drinking water can be provided to cities like Delhi. Then there is the environmental toll on the river and its aquatic life.

Manoj Mishra a former civil servant, and convener of the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan (Yamuna Live Campaign) dedicated to the reviving the river and its floodplains, says: “There are apprehensions of devastation due to the Lakhwar-Vyasi project amid natural calamities. Yamuna can still live with Vyasi, not Lakhwar. The future water requirement for Lakhwar is also not logical.”

One of the main arguments in support of the project is that it will supply drinking water to five states, especially the National Capital Territory of Delhi.

But the Delhi Jal Board, the government agency responsible for the supply of potable water to the capital, has highlighted that greater reliance on recycled water could help it manage its water needs easily. In 2015 Delhi’s water minister publicly stated that proper management of water would mean the city would not need external sources.

Despite the disasters, the protests and environmental concerns, as he visited the region to gather public support for the assembly elections on 14 February, on 4 December 2021 Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Vyasi project.

Meanwhile, five months ago solar-powered street lighting was installed in the village of Lohari. In contrast to the dangers presented by the dam, this hopeful gesture points to a different direction energy policy can still take.

The Third Pole spoke with an official for the Vyasi project on the complaints and concerns surrounding the Lakhwar-Vyasi dam complex, including the impact on the Yamuna River’s biodiversity, issues of land compensation and relocation, and impact in terms of increasing the risk of disasters. They declined to comment on the record for this story.