Syed Ali Zia Jaffery :

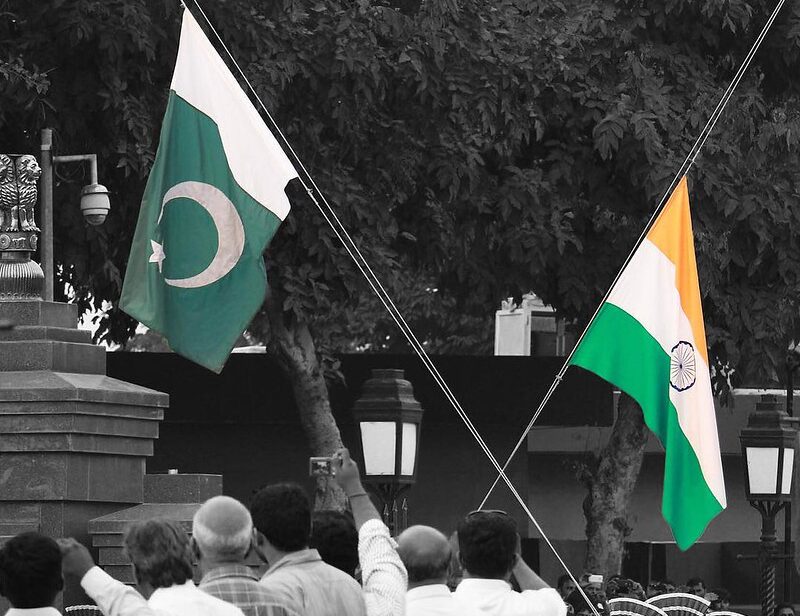

February 2024 marked the 5th and 3rd anniversaries of the Pulwama-Balakot Crisis and the Indo-Pak ceasefire agreement on the Line of Control (LoC), respectively. While the Crisis brought the two nuclear-armed neighbors perilously close to a catastrophe, the ceasefire agreement brought about a temporary end to violence on the most militarized boundary in the world. Unfortunately, neither the said nuclear-tinged crisis nor the ceasefire agreement portends better days ahead for Indo-Pak relations.

If anything, the crisis has set dangerous precedents of attacking the mainland and posturing for horizontal escalation. As for the ceasefire, it cannot help address the root causes of the Kashmir imbroglio. This is not the first ceasefire agreement as both countries have made four attempts to silence guns along the LoC since 2000. The results of these efforts show that any ceasefire is unlikely to pave the way for further steps towards enduring peace between the two countries.

That being said, it does provide relief to civilians on both sides of the LoC. Regardless, these two episodes loom large as the new coalition government finds its feet in Pakistan, and India readies itself for the upcoming general election. Notwithstanding the importance of these elections, it is unlikely that they will change the state of Indo-Pak relations. In the short term, no breakthrough should be expected.

India’s hawkish policy towards Pakistan

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership, India has adopted a tough and muscular approach towards the disputed Kashmir region and, by extension, Pakistan. As a lifetime member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Modi is committed to advancing Hindu nationalism, which also affects his approach to Kashmir. His government has overseen an exponential increase in extrajudicial killings, torture, and custodial deaths, with violence in the Kashmir Valley reaching its peak when a young Kashmiri activist Burhan Wani was shot dead in 2016 by the Indian security forces who consider him a militant.

Modi has blamed Pakistan for all the violence, chaos, and instability in Kashmir; Islamabad’s alleged role in supporting inimical Kashmiri groups has long been a big issue for New Delhi. As a result, ties with Pakistan have been ruptured, as evidenced by a complete breakdown of bilateral dialogue, the use of force, and increasing anti-Pakistan rhetoric. All this has ended any prospect of a thaw that might have resulted from initial parleys between Modi and Pakistan’s then-premier, Nawaz Sharif. Modi’s change of tack versus Pakistan can be gauged by India’s use of force during the Uri and Pulwama-Balakot crises. This was not only followed by nuclear jingoism from India’s top leadership but also, a few months later, the scrapping of Kashmir’s special status.

New Delhi-Islamabad relations have since nosedived; barring the still-intact ceasefire on the LoC, there has been no positive development between the two countries. More worryingly, top Indian officials including the Defense Minister have talked about militarily taking back territories from Pakistan. Given the importance of such an aggressive stance towards Pakistan in helping build Modi’s strongman image, which resonates well with his support base, any discussion of normalizing ties is unlikely especially with the general election coming up.

India is also unlikely to show restraint in a future crisis — to avoid audience costs, New Delhi will have to act more aggressively in a future standoff with Pakistan. As I have argued elsewhere, “a climb-down from a Balakot-like response” will negate New Delhi’s narrative of successfully calling out Pakistan’s nuclear bluff and creating a “new normal” against that country. If India does not hit targets deep inside Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) or mainland Pakistan for that matter, any crisis might only be considered a normal cross-LoC skirmish, calling into question its resolve. With both restrained crisis behavior and peace offers appearing to be less attractive policy options for the Modi government, the prospect of resuscitating the Indo-Pak dialogue is all but low.

Pakistan’s feeble political setup

Pakistan’s new government has its work cut out as far as managing the country’s crisis-hit economy is concerned as soaring inflation, growing poverty, and low forex reserves pose major challenges. Navigating these issues, especially with the help of a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), will require introducing painful structural reforms. This exercise will be both time-consuming and politically disastrous for all parties in the weak coalition government, leaving little room to focus on constructive diplomacy with India.

Starting afresh with India, even as a goodwill gesture, will require political capital, which the new dispensation lacks. Marred by massive pre- and post-poll rigging, the recently-held election did not result in former premier Imran Khan’s return to power despite his electoral success. This has exacerbated political instability; with Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) fighting in the courts and on the streets to get its mandate back, the coalition government is likely to face increasing pressure in the days to come. Consequently, shaping an already unfavorable public opinion in support of dialogue with India will be next to impossible. Lacking confidence and bandwidth, Pakistan’s new government is unlikely to prioritize improving ties with India. If anything, India will be way down the pecking order of its policy actions.

While the military’s buy-in for resuming dialogue will certainly be a major factor, it is unlikely that the civilian government will get it in these challenging times. That being said, an increase in the military’s formal role in the country’s economic management under the current government may lead to a reassessment of the economic dividends of making peace with India.

Most importantly, making concerted efforts to improve ties with India will give Khan and his charged supporters yet another opportunity to discredit the government, inside and outside of the country’s parliament. This, coupled with India’s lack of interest in negotiating with Pakistan, means that any kind of headway is not in the offing. Therefore, Pakistan will find it untenable to explore any possibility of dialogue with India, especially given an ever-increasing political crisis.

A costly logjam

The lack of political will on both sides suggests there are slim chances of a major breakthrough in Indo-Pak relations. Modi’s government in New Delhi will run the risk of incurring audience costs if it tries to mend fences with Pakistan during peacetime, or shows restraint in a crisis. Meanwhile, mired in an acute economic crisis, Pakistan will not have the space to focus on turning a page in its relations with India. Also, given the questionable and seriously contested legitimacy of Pakistan’s new government, it will be extremely difficult for Sharif to get support and acceptability for extending an olive branch to India.

All this will continue hampering regional connectivity. With overland trade routes closed, Pakistan and India are missing opportunities to expand their economic footprints. Certainly, as Rabia Akhtar and Moeed Yusuf argue, overland routes will enable India and Pakistan to increase their access to Central and East Asian markets, respectively. Furthermore, this Indo-Pak stalemate is likely to persist due to the ever-intensifying rivalry between China and the US. Pakistan will, for example, remain suspicious of the US bid to prop up India as a bulwark against China. On the other hand, both the US and India will see Pakistan’s ties with China as a way for the latter to increase its clout in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). All these apprehensions will not bode well for Indo-Pak relations going forward.

source : southasianvoices