North Korea’s latest missile outrage has stolen the global headlines from a potentially even more significant turn of events in world security. That is the seemingly sudden resolution of the border confrontation between Chinese and Indian troops in an area known as Doklam in disputed Himalayan territory.

The Indian government has been careful to let China save face and has not declared victory since this risky, months-long deadlock came to an end. See India’s initial official statement, crafted with all the excruciating minimalism that Ministry of External Affairs officers spend years mastering (this was followed by a gentle clarification that both sides were withdrawing forces). The Chinese state media, meanwhile, has been quick to brag that the outcome involved the withdrawal of Indian forces, but conspicuously silent on the apparent cessation of the Chinese road-building activity that started the whole crisis.

This was the sharpest confrontation between the armies of the world’s two most populous nations since a bitter 1962 war and a nasty 1967 skirmish. At one stage, elsewhere on the disputed border, relations degenerated to a stone-pelting melee, caught here on video. These are two nuclear-armed mega-states, neither of which seeks or can afford war. So how they found themselves in the Doklam crisis, managed it and then de-escalated it holds important lessons for nothing less than peace and stability in their shared Indo-Pacific region, indeed globally.

A central but most delicate question, of course, is who won. India was first to announce the withdrawal of its forces, and China did not take long to claim that its road-building was not necessarily over but could eventually resume when the weather is right. Such points reinforce the superficial reading, which some Western media were surprisingly quick to accept, that China had essentially forced India into a somewhat humiliating backdown.

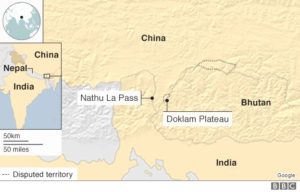

This is actually quite unconvincing, as a straightforward review of the evolution of the dispute would suggest. To recap, the face-off began in June when Chinese troops began to extend a road into the Doklam area. This is land disputed not by China and India but by China and Bhutan. The Chinese were presumably caught by surprise when their effort to change facts on the ground was interrupted by Indian troops (consistent with the longstanding arrangement for India to protect Bhutan’s defence interests). India’s stated intent all along was not to retain its forces in the area, or even to compel Chinese troops to leave, but to stop the provocative building of Chinese infrastructure on contested land.

I share the broad assessment of such analysts as Oriana Skylar Mastro and Arzan Tarapore, Jeff Smith and Shashank Joshi – that at Doklam, China was caught off balance by India’s military response of deterrence by denial. No amount of full-throated bluster, condescension or war talk from Chinese party-state mouthpieces could make India’s forces budge. The Global Times insisted there was no room for negotiation. Yet within weeks, we saw a negotiated resolution. This makes it more likely that others will discount Chinese threats in future.

This firmness on the ground, combined with the patient and low-key nature of India’s diplomatic negotiations, driven by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and Foreign Secretary S Jaishankar, may provide a new template for handling Chinese coercion. There may well have been special factors, not least the desire for the forthcoming BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) summit to be free of strife, or worse still, of an Indian boycott. Scholars at the Center for Strategic and International Studies have exhaustively demonstrated how, contrary to the vision of inevitable Chinese hegemony, most of China’s efforts at coercive influence in maritime Asia in the past decade have ended in stalemate or damage to China’s interests. Now India has delivered a case study on land.

My earlier Lowy Institute research has identified Indians’ low levels of trust in China (with 83% considering it a threat). A similar poll today would presumably show even less love lost. Sooner or later, grand ambitions like the Belt Road Initiative will stumble if Asia’s other emerging giant is not shown at least some of the respect it sees itself warranting as China’s civilisational peer.

Of course it is too early to identify all the lessons of Doklam. But unless China brings back the bulldozers soon, India will have won this round. And it did so without substantial involvement by the US. This is a tangible riposte to claims that the rest of Asia should embrace a China-centric order if it finds itself having to live without an American-led one.

Others in the Indo-Pacific, such as Japan, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Australia, will be watching with more than academic interest.

The article appeared in Lowy Institute, the Interpreter on 31/08/2017