by Chandra Prakash Singh 23 October 2019

The word ‘Madhesh’ implies much more than a physical composition of the space that stretches across the southern belt of Nepal. It includes the cultural and lingual space that exists as a basis of identity amongst the people residing in the region. It has also a definite and distinct regional, cultural and lingual space of Madhesh which exists in the minds of those who inhabit it. Frederick Gaige maintains the close association of ‘Tarai’ symbolising colonial mentalities, which he referred to as the process of ‘Nepalisation’ of Madhesh.Others are also of the view that while Tarai exists in the context of Nepal, the word is more generic than claimed – Tarai regions are also found in India, Bangladesh and Bhutan.Thus Madhesh seems to carry more significant historical, regional and cultural connotations than the term ‘Tarai.’ While the terms Tarai and Madhesh may carry specific regional and cultural connotations, both are generally used in the context of contemporary Nepal for reference to the largely agrarian southern belt of the land-locked country. Madhesh’ is used here to imply cultural and geopolitical terminology because they are intrinsically linked to political and cultural implications of the Madheshi movement and agenda.

Division and demarcation of areas

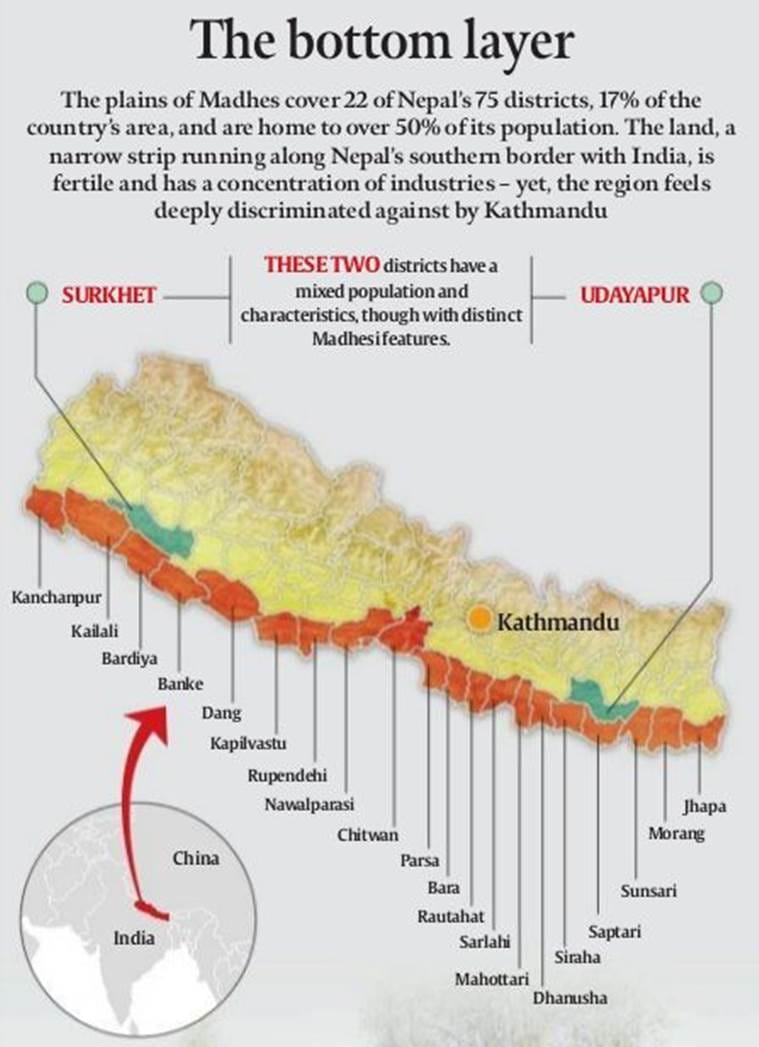

The Tarai region comprises three distinct units – Eastern, Central and Western Tarai. Thus, identifying Chitwan and Dang, the districts of Inner Tarai or Bhitri Madhesh, as “(punctuations) of the geographical continuation of the Tarai in Nepal.”If we stretch this point further we see that there are generally two schools of thought in pondering over what it means to be Madheshi. The lines of identification have distinct and specific political connotations and hence have served as the basis of much rhetoric surrounding the ongoing Madheshi movement for rights and representation in the Nepal.

The first school understands Madhesh as a regional entity in its geographical depiction. Thus, the people living in this region have been broadly called Madheshi or Madheshiyas. This view includes that the term Madhesh refers to all non-Pahadis which includes the traditional caste hierarchy such as Brahmin, Kshatriya, Baisya and Dalits, and indigeneous Janjati ethnic groups, other native tribes and Muslims. Tarai-based parties such as the Terai Madhesh Loktantrik Party (TMLP) headed by Mar Mahanta Thakur, share sentiments with this school of thought in defining who Madheshis are and ultimately, who they claim to represent with their party manifestos.

The second interpretation of Madheshi identity is seen through the sociological lens of identity. Krishna Hachhethu describes the region as “a traditional homeland of tribal people and the people of Indian origin.Thus the second definition of Madheshis proposes that the basis of identity lies in what is termed as “people of Indian-origin”. For generations many Madheshis share close associations i.e. through marital ties with communities living across the open border. In this sense, Madheshis shared predominant lifestyles, food habits, language and culture common with the people who live across the Indian border in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. This has sometimes raised suspicions of loyalty and identity amongst Pahadis with decision-making positions in the centre of Nepalese politics. This definition is important in understanding the social reality/relevance to identity politics going on at the moment because it implicitly refers to specific pockets of communities amongst the Madhesh population. This selective aspect of definition implies a distinction between Madheshis of Indian-Origin and everyone else who lives in Madhesh.

Political movements of Madheshi

It is also to mention here that even though Tarai and Inner Tarai occupies about only 17 per cent of Nepal’s total land area, they are home to some 49per cent of Nepal’s population. Though these figures continue to be disputed based on one’s understanding of who Madheshis are, one thing for certain is the historical and continued exclusion of the Nepalese state through the lack of representation and development given to these regions. Should the Madheshis be defined regionally, they would constitute almost half of the population. That would give them a very strong case of exclusion from Nepalese society. i.e Electoral under-representation, discrimination in employment in civil service and governmental bodies etc. The question of identity amongst the Madheshis and other inhabitants of Tarai who claim counter identities are crucial in analysing the rise of Taraibased parties who claim to champion a congruent Madheshi cause.

Looking at the Madheshi Protest that occurred in 2007 through the socio-historical lens had generally been popular with academics, policy makers and non-Tarai observers of the movement. This view frames the movement with hindsight of centuries of marginalisation and foresight of political and social change that has hit Nepal with the outstripping of royal power in the state. As a matter of fact, Madheshis have been treated unfairly and denied rights as citizens of Nepal throughout the history of Nepal. These had manifested in the form of discriminatory policies issued by the King and state at respective periods in history.The centralised system of taxation, privatising of land tenure, imposition of corvee labour and birta land grant practices were some of the common instruments of exploitation that began during the Rana Dynasty. Despite the Jana Andolan in 1990, aristocracy continued to control national politics and state affairs. High castes of hill communities continued to dominate the highest appointments in civil service (police, military etc) and government offices. More directly, it failed to ensure power-sharing and an equal distribution of resources among Madheshis, Janajatis, women, dalits and other indigenous nationalities living in the Tarai.

Historical discrimination and marginalisation

One can not possibly ignore this fact that many Madheshis were for centuries, denied Nepali citizenship until 2007. Before 2007, it seemed that state design had erected hurdle to delay or indirectly deny the process. A Madheshi had to produce his Land ownership certificate where he sought to obtain his citizenship certificate and passport. On the same count, he would not be able to attain a Land Registration Deed (lalpurja) if he could not produce his citizenship certificate. This has led to pressing issues of landlessness amongst the Madheshis, Janajatis, Dalits and Muslims from the Tarai. Without citizenship certificate, Madheshis were not able to vote, buy or sell land, attend college education and apply for government jobs amongst other things. State and social engineering had in a way guaranteed the proliferation of discrimination against the Madheshis whether that was the intention or otherwise.

Thus, the socio-historical perspective traces many examples of marginalisation and unfair treatment practiced on the Madheshi community. It argues that a cumulative process of shared grievances about many matters and aspects of their lives had united the many different groups under the flag of One Madhesh, One Pradesh and subsequently fuelled the movement for change in Nepal’s democratic transition. It recognises the Madheshi movement as a response to years of marginalisation by the state throughout history. The weakness of the above-mentioned perspective is its inability to timely account for the occurrence of the movement. If the movement was caused only by conditions of unfair treatment and marginalisation, why did it take 239 years to Madheshis to feel united or brave enough to rise up against the status quo? While this perspective justly addresses the grievances among the community, it fails to provide a timely understanding in explaining how the 2007 protests spiraled into the biggest Madheshi movement ever.

Interestingly, the Madheshi movement gained such momentum because it was not only ethnic Madheshis who called out to the state demanding rights. Many other groups including the Janajatis, Muslims, women groups and dalits joined at the forefront of the push for rights and representation. Apart from this the ‘One Madhesh, One Pradesh’ slogan that seemed to resonate with a collective identity of Tarai inhabitants seemed to work at that time in uniting Madhesh. In other words, the movement took off because its members were united by a collective identity of marginalisation by Kathmandu more than anything else. But even today there are many in Tarai, both ethnic and non-ethnic Madheshis who sincerely believed and continues to that the only way to have a significant voice loud enough for the elites in Kathmandu to pay attention to is by presenting a united Madhesh to the rest on Nepal.