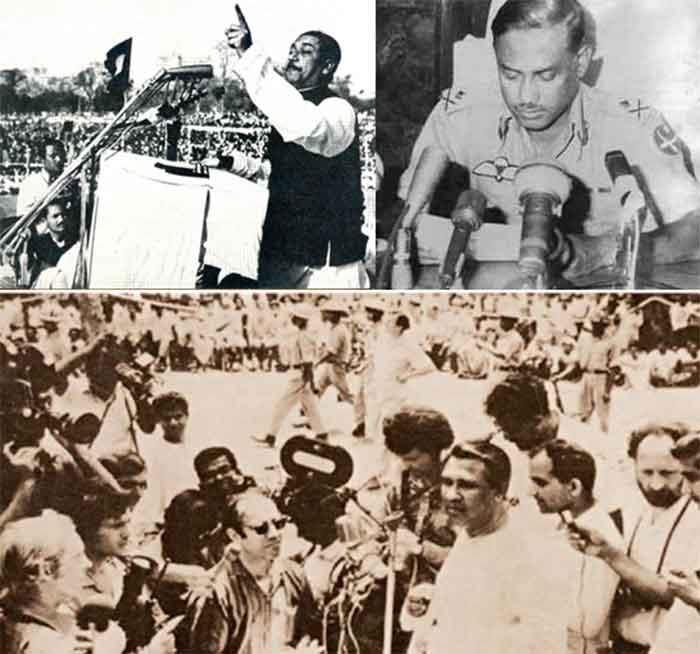

Photo (Clockwise, from left to right): Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Ziaur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmed

Lately, in addition to several reforms, the post August 5, 2024 Interim Government (IG) of Bangladesh has also embarked upon the task of investigating, unravelling and rectifying what it called the “exaggerated, imposed history” of Bangladesh.

The “imposed history”

The “imposed history” in question relates mainly to the politically inspired disinformation and misinformation of the deposed Hasina government that had distorted history, focusing, in particular on the following narratives of the “distorted history”: ‘the declaration of independence of Bangladesh’ i.e., who declared the independence of Bangladesh first; the honorific, the ‘father of the nation’ i.e., whether the honorific should be the monopoly of one person, namely, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the father of the deposed leader and not include a host of other leaders who made significant contributions in the liberation of Bangladesh?

Beginning with the issue of ‘declaration of independence, this article is an input to the debate on the broader issues of the “imposed history.”

“Declaration” of Independence

During Shiekh Hasina’s rule and under the instruction of her government, textbooks at primary and secondary levels inserted the following narrative, “Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared independence through a secret wireless message minutes before the Pakistan army cracked down on the civilians and arrested him in the early hours of March 26, 1971.”

Then, there are also those who claim that Sheikh Mujib’s March 7, 1971, public speech at the Dhaka racecourse ground where, among other things, he also said, “…this time the fight is for freedom, for liberation…” should be treated as the first declaration of independence.

Authenticities of these claims – Mujib’s declaration of independence on March 26 through a secret wireless message and his March 7, 1971, speech as the first calls of independence – have since been questioned.

So far no concrete evidence of Sheikh Mujib’s March 26 ‘secret wireless message’ of ‘declaration of independence’ has been provided, and therefore, until concrete evidence is made available it would not be appropriate to treat the ‘secret wireless message’ narrative of the ‘declaration of independence’ as genuine and nothing more than hearsay.

Many also argue that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s March 7, 1971, racecourse speech which no doubt was inspiring and to some extent, transformative, was by no means a ‘declaration of independence’ either, for if it were, the Pakistan authority would have arrested Mujib right then and tried him for treason. They did not. Besides, the speech included several conditions for transfer of power and had the Pakistan government accepted those conditions, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would have been the Prime Minister of Pakistan and not of Bangladesh. Therefore, it would be misleading if not a gross factual error to treat his March 7, 1971, as proclamation of independence of Bangladesh.

Who then made first declaration of independence?

According to the IG it was not Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, it was former President Ziaur Rahman made the first “declaration of independence” of Bangladesh” on March 26 and 27, 1971, through radio announcements in Chittagong.

Ziaur Rahman, a Major in the Pakistan army in 1971 who was then based in Chittagong rebelled on March 25, 1971against the Pakistan Army/Pakistan state for their brutal crackdown on the innocent “East Pakistanis,” and thus declared independence through two back-to-back radio announcements, first, on March 26 and then again, on March 27, 1971, at a makeshift radio station in Chittagong.

Ziaur Rahman’s March 26 and 27, 1971 radio announcements were the very first “declarations” of independence which everyone heard. Furthermore, these announcements also signalled in a more concrete manner, that a Bengali section of the Pakistan army has rebelled and that a liberation war has commenced and thus the claim that it is Ziaur Rahman and no other who made first the declaration of Bangladesh.

All true but can we still treat these announcements as “declaration” for independence?

To answer the vexed and the contested question as to who made the very first “declaration” of independence of Bangladesh, it may be helpful to explore these announcements/declarations within the framework of theoretical precepts that constitute, what is known as the ‘Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).’

‘Unilateral Declaration of Independence’ (UDI): Theoretical Precepts

The concept of ‘Unilateral Declaration of Independence’ (UDI) or “declaration” of “unilateral secession” that describes more accurately, the context of Bangladesh’s separation from Pakistan, is defined as a “formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state from which it is seceding.”

The term, UDI was first used in 1965, when Ian Smith, the colonial administrator of Rhodesia (presently, Zimbabwe) decided to severe connections with the mother country, the UK, and declared independence and seceded, without an agreement with the mother country.

Thus, judging from the theoretical precepts of the UDI which implies formal announcement of separation of a sub-national entity from an existing country into a new nation, without the agreement of the mother country and by a group/individual that officially represents the citizens of the seceding unit, neither Sk. Mujib’s yet-to-be-proven clandestine telegram of March 26 nor his March 7, 1971 racecourse public speech nor even Ziaur Rahman’s March 26, 27, 1971 radio announcement where Zia clearly stated “…hereby declare that the independent People’s Republic of Bangladesh has been established…” can be considered as UDI, for none of these announcements revealed nor envisaged a “…formal process leading to the establishment of a new state…” nor were these announcements made by entities that had the representational authority of the separating unit, namely, the people of the then East Pakistan to declare separation, formally.

So, who made the first declaration of independence that conforms to the theoretical precepts of an UDI?

To answer this question and in addition to Mujib’s and Zia’s announcements, we also need to acknowledge another ‘declaration of independence’ which was made on April 10, 1971, by the Bangladesh-Government-In-Exile (BGiE) in Mujib Nagar. Let us examine.

The April 10, 1971, Proclamation

On April 10, 1971 the Bangladesh-Government-in-exile made the following declaration at Mujib Nagar, then a liberated area in Bangladesh which among other things, stated, “…declare and constitute Bangladesh to be sovereign People’s Republic…” and more importantly, the declaration was made by an entity, the BGiE, an elected body, that officially represented the seceding entity, the then East Pakistan, the subnational entity of Pakistan. Through the Proclamation, the BGiE also formally commenced an organized liberation war and led the war that contributed to liberation and the emergence of Bangladesh, as an independent state.

Therefore, in the context of the theoretical precepts of an UDI – a formal declaration of separation by a team that represented citizens of the seceding unit, – the only “declaration” that qualifies as the first official and acceptable proclamation of independence of Bangladesh is the one, made by the BGiE on April 10, 1971 at Mujib Nagar.

But then, what about these other dates and milestones which are no less important: the March 7, 1971, Speech of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his March 26, Secret Telegram and indeed, what about Ziaur Rahman’s March 26, and 27, 1971 Radio announcements in Chittagong? Do we discard and/or ignore these announcements/statements?

Not at all, we must acknowledge and remember these dates and events as important milestones in Bangladesh’s march towards independence but not as UDI of Bangladesh. April 10, 1971, should be commemorated as the official UDI of Bangladesh.

Honorifics: Individual Vs. Collective

Another issue which is being debated a great deal especially since July/August 2024 uprising, involves the Honorific, ‘Father of the Nation’ which has been conferred on Shiekh Mujibur Rahman at the inception of Bangladesh in1971.

Questions have been raised as to whether Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who no doubt played the most important role in the processes that led to the independence of Bangladesh, did it alone and deserves the monopoly to the honorific, the ‘Father of the Nation’?

Many argue and with good reasons that it is indeed true that Sheikh Mujib played the most pivotal role in the political mobilisation of the “East Pakistanis,” at whose call millions rose, resisted and fought against Pakistan government’s violent and discriminatory treatment of the East that ultimately led to the liberation war and creation of Bangladesh, it is equally important to remember that other leaders including the academics as well as the students played crucial parts first, in conceptualising the ‘two-nation theory’, and later, in political mobilisation in resistance and the liberation war that led to the idea and creation of Bangladesh. Should these heroes and their contributions not be venerated?

In other words, giving all credits of independence of Bangladesh to one individual, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and conferring upon him the honorific, the ‘Father of the Nation’ while ignoring others is not just unfair but a huge disservice to the nation. People do have right to know their heroes and pay their respect where these are due. Many thus suggest that it would make sense to confer two-tier honorifics – one to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib, who towered over all in the mission of liberation and creation of Bangladesh, be given the honorific, the ‘Father of the Nation’ and others, the ‘Founding Leaders.’

Lionisation/Demonisation of leaders

Another issue which has been a product of yet another act of disinformation and misinformation, something which has been somewhat of a national disgrace is this practice of lionisation and demonisation of leaders.

Influenced by political motive and propaganda, people in Bangladesh seem to demonstrate this despicable habit of either lionising or demonising their leaders. They glorify and often put their preferred leaders on a pedestal, while demonise those who belong to the other side of the political spectrum. This is unhealthy.

The practice has affected most two of Bangladesh’s towering leaders – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Ziaur Rahman.

With active encouragement (“imposed history”) of the deposed Hasina government, the loyalists lionised Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to such an extent that they have made him a deity and at the same time, they demonised Ziaur Rahman, the other national hero, a freedom fighter in the ugliest of manners, as a traitor!

In comparison to Mujib loyalists, the admirers of Ziaur Rahman are a bit less effusive about Zia but emphatic about his nation-building contributions and more importantly, the Zia admirers do respect Mujib, as the father of the nation but also criticise him for his mistakes.

It is hard to imagine Bangladesh without Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Ziaur Rahman’s strong and visionary leadership at a critical juncture of Bangladesh that helped, “…put a collapsing nation (Bangladesh) on its feet…” and the country to advance do deserve due recognition.

Notwithstanding, both committed mistakes. Sheikh Mujib subverted democracy, brutally suppressed political opponents, encouraged extra-judicial murder that caused deaths and injuries to many of his opponents, including Bangladesh’s first murder-in-custody of a high-profile political opponent, Siraj Sikder. Similarly, Ziaur Rahman, a war hero and a transformative leader has been criticised for deaths of many soldiers who mutinied against him, who allegedly were executed through dubious trail processes.

In other words, however great the leaders might have been/are, they do make mistakes, and the challenge is to deal and reconcile the virtuous contributions of heroes with their not-so-virtuous deeds in a truthful and mature manner? So, how do we go about it?

Accounting leaders in a balanced way: the China example

The answer to the conundrum came from a recent account of a BBC journalist who travelled extensively throughout China, asking young Chinese of their impressions of Chairman Mao, “How do you evaluate Chairman Mao?” Majority answered, “He did both good and bad.” The BBC journalist asked, “What are the good and bad deeds of Mao?” They replied, “Chairman Mao united the country and restored China’s sovereignty, but his Cultural Revolution destroyed the economy, and millions died of starvation.” Then the BBC journalist asked, “I can understand how you learnt of Mao’s good deeds but then, how did you come to know his bad ones?” They answered, “Why, these are in our school textbooks.” Then the BBC journalist asked, “How do you reconcile Chairman Mao’s good deeds with his bad?” The young Chinese answered, “Chairman Mao’s good deeds inspire us and reminds us of the value of unity and importance of sovereignty; his bad deeds have taught us what not to do.”

Indeed, Bangladesh needs balanced accounting of their leaders, and this is key to nation-building.

Notwithstanding their mistakes, a nation needs genuine role models to respect and be inspired by their virtuous deeds while avoiding their slippages, for as Confucius once said, “A nation without role models is like a blind person who does not know where to put the hands and feet on.”