By Dr. Quamrul Ahsan1 and Dr. Anisul Haque2

1Former Assistant Professor, 2Professor

Institute of Water and Flood Management (IWFM), Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Dhaka

1 Corresponding author: quamrul@icloud.com

The Dead Zone

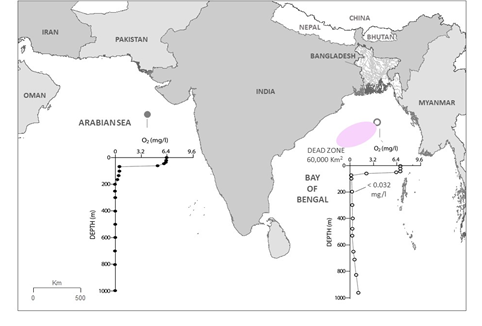

A Dead Zone in the Bay of Bengal (BoB), nearly half the size of Bangladesh and at depths 70m and below, has been discovered in recent years by a group of multinational scientists. This oxygen-depleted zone, called hypoxia, is the third-largest Oxygen Minimum Zone (OMZ) in the world after the OMZs in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean and the Arabian Sea. Compared to the neighboring Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal OMZ is somewhat different in nature. It shows a trace of oxygen at 70m depth and below, ranging from .032-.064 mg/l, which is below the standard Oxygen level (5 mg/l) needed to support aquatic life. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea has no oxygen, causing devastating effects on its ecosystem and losing its Nitrogen balance unlike any other ocean in the world. Toxic algal bloom and massive fish kills are rampant in both the flanks of the Arabian Sea (Indian and Omani coasts), caused by the southwesterly summer monsoon winds that trigger upwelling circulations and bring the nutrient-rich and oxygen-depleted bottom ocean water onshore. The Bay of Bengal OMZ, however, hasn’t gone to that level yet but has reached its tipping point. Evidence shows that the Bay of Bengal OMZ is alarmingly expanding as reflected by its intensification. The trend is set to continue due to global warming, changing river runoff, and circulation patterns in the Bay of Bengal. Anthropogenic inputs of nutrients, such as Nitrogen and Phosphorus, and organic Carbon, have adverse effects on the OMZs. The potential ramifications of this OMZ are huge.

Dead Zone of 60,000 km2 has been discovered by a group of multinational scientists in 2016. The Bay of Bengal OMZ still shows a trace of oxygen bellow 70m depth, ranging from .032-.064 mg/l, albeit way below the Oxygen level (5 mg/l) needed to support aquatic life and other uses. On the other hand, the Arabian Sea has no oxygen, causing devastating effects on its ecosystem and losing its Nitrogen balance unlike any other ocean in the world. O2 profiles reproduced from Naqvi et al., (2006)

Ecological and Socioeconomic Ramifications

The Bay of Bengal has in excess of 400 million people living immediately around its rim, many depending on the Bay for their livelihoods and food security. Extreme OMZ would have dramatic impacts on the marine ecosystems, including commercial species that are already over-exploited. A slight drop in Oxygen levels could lead to devastating effects on the ecosystem across the Bay of Bengal and intense denitrification can occur as seen in the Arabian Sea.

Coastal hypoxia (water with little oxygen) caused by upwelling oceanic circulation, lead to massive fish killings; and is often seen on the Indian shelf of the Arabian Sea and on a limited scale in the Bay of Bengal. In addition, the nutrient-rich bottom water, when brought to the surface by upwelling circulation, may trigger a massive harmful algal bloom, as seen in the Arabian Sea. This has knock-on effects on food webs, carbon export and burial, and nutrient cycling in the coastal waters. A remarkable feature of the Bay of Bengal, however, is the massive influence of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) system, which sets it apart from the Arabian Sea. The GBM river waters make the Bay of Bengal water more stable and stratified that prevents upwelling circulation. However, the GBM river system brings millions of tons of sediments into the Bay, which carries organic materials and nutrients that demand dissolved oxygen from the ocean water. A small reduction in oxygen, however, could have a devastating effect on the ecosystem across the Bay of Bengal. Furthermore, the Bay of Bengal, being connected to the Indian Ocean, is particularly susceptible to increased temperature as the Indian Ocean is warming faster than any other ocean in the world. Higher temperatures may accelerate the oxygen depletion rate in the water column.

The biogeochemistry of the Bay’s water remains very poorly studied relative to those of the Arabian Sea and many other ocean regions. While Bay of Bengal phenomena are widely recognized to be of major, far-reaching importance, large uncertainties remain about how the system functions currently and how it will respond to environmental change (IPCC). Particularly, a large projected increase in nutrient discharge and the recent launch of major engineering projects to the dam and/or divert the Ganges and Brahmaputra, have major implications on the future discharge of water and organic matter and add to this uncertainty.

The Bay of Bengal at a Tipping Point

Even a trace of oxygen present in the OMZ reflects a dynamic balance between the mixing of atmospheric oxygen into OMZ waters and the oxygen uptake by the biological processes that degrade organic materials. Therefore, an increased influx of organic matters in the OMZ waters would break this delicate balance and make the OMZ waters anoxic (no oxygen), and consequently accelerate the denitrification process (loss of nitrogen) in the Bay of Bengal. Moreover, an increase in the flux of anthropogenic nutrients (Nitrogen and Phosphorus) into the Bay, as projected for the coming decades with the changing the intensity of summer monsoon, would increase in primary production (algal growth) which would demand additional oxygen from the already oxygen-depleted OMZ waters.

High-intensity southwesterly monsoon summer winds may trigger upwelling circulation that brings nutrient-rich hypoxic (very little to no oxygen) bottom water in the surface of coastal waters. Akin to the Arabian Sea, this phenomenon may trigger the production of high concentration algae and further enhance oxygen depletion in coastal waters that may potentially kill, aquatic life including commercial fish, and destroy the coastal ecosystem functions.

It is also true that an enhanced summer monsoon, due to global warming, would increase river runoff and organic material flux into the Bay water, and may cause the removal of a small trace of oxygen in the OMZ waters and accelerate denitrification (loss of nitrogen) processes in the water column; causing an efflux of greenhouse gas (NOx) into the atmosphere, like in the Arabian Sea.

Therefore, the Bay of Bengal OMZ is sitting on a biogeochemical “tipping point” where any process of removing the last trace of oxygen, through either anthropogenic nutrients input, enhanced flux in organic materials due to climate change, or upwelling circulation, would put the Bay of Bengal ecosystem and the livelihood of the people at severe risks.

What is Next?

The global warming and human interventions particularly in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin in the upper riparian countries have an enormous influence on the physical and biogeochemical state of the Bay of Bengal. Thus it is, important to know how the Bay of Bengal will evolve in the decades to come. Extensive field observations not only in the Bay of Bengal but also in the GBM basin would shed light on the ecological and biogeochemical health of the Bay of Bengal. It is important to know how hypoxia, ecosystem functions, and key biogeochemical phenomena will respond to projected environmental change in the future (IPCC) and ultimately fit in the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 objectives and the Blue Economy ambition of Bangladesh.