By Patrick Barron

Natural disasters do not discriminate in who they impact. Yet individuals’ ability to recover is strongly shaped by systems of social and economic stratification. While the caste system has been outlawed, with the 1990 and 2015 constitutions making caste discrimination illegal, most lower caste groups continue to lag behind others with 90 percent of Dalits living below the poverty line.

The first round of IRM, conducted in the weeks after the disasters, found that both low castes and others were similarly affected by the earthquakes: 44 percent of the homes belonging to low castes were destroyed compared to 50 percent for high castes.

How is such structural inequity affecting earthquake recovery? The Asia Foundation’s Independent Impacts and Recovery Monitoring (IRM) longitudinal research allows us to assess the differing experiences of groups over time. IRM includes surveys of almost 5,000 people and in-depth, qualitative fieldwork conducted at roughly six month intervals following the earthquakes, allowing for an evaluation of which groups are recovering, which are not, and why.

Common problems, collective responses

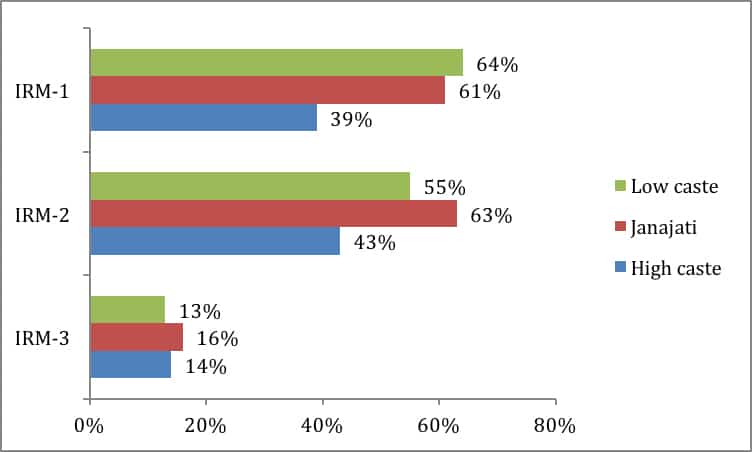

The earthquakes did not affect those of low caste more than others. The first round of IRM, conducted in the weeks after the disasters, found that both low castes and others were similarly affected by the earthquakes: 44 percent of the homes belonging to low castes were destroyed compared to 50 percent for high castes. Common problems led to collective responses. After the quakes, frequent examples were found of people of different castes, including Dalits, helping each other and sharing shelters. Researchers founds cases where high caste people allowed landless Dalits to build shelters on their land. In the early post-earthquake period, low caste people were much more likely to have received aid than others (64% versus 39% of high caste people). Concerted efforts by aid providers to ensure that Dalits and other low castes received support, strong community norms around distributing aid equally, and a sense of solidarity among the earthquake-affected that crossed identity lines combined to help low caste people cope in the immediate aftermath of the disasters.

Emerging differences

However, the first round of research also pointed to the potential for pre-existing forms of exclusion and discrimination to re-emerge with the shift from relief to reconstruction. Subsequent rounds of IRM have shown that low caste groups are now lagging in their recovery. But the third round of research, conducted in September 2016, found marked differences in recovery between different groups. One-and-a-half years after the earthquakes, 82 percent of low caste people whose houses were impacted said they had yet to start rebuilding, compared to 71 percent of high castes. Almost one-quarter of those of low caste said they had made no repairs to their temporary shelters, compared to 11 percent of high caste people. Low caste people were twice as likely as high castes to report decreases in food consumption over the past year. And they were almost 50 percent more likely to say a family member continued to suffer from trauma than other groups.

The third round of research found marked differences in recovery between different groups. One-and-a-half years after the earthquakes, 82 percent of low caste people whose houses were impacted said they had yet to start rebuilding, compared to 71 percent of high castes.

Diminishing aid and debt traps

The second and third rounds of IRM identified two worrying trends. First, over time low caste groups have become increasingly less likely to receive aid compared to others. As Figure 1 shows, whereas a larger share of low caste people in the first round received aid than did others, this pattern has shifted over time.

Figure 1: Proportion who received aid—by caste

Second, with relatively little aid available, and recovery slow, low caste groups are turning to borrowing. Taking loans can be an important strategy for boosting recovery. However, the data suggest that borrowing is not helping many low caste people recover, that they are still facing credit constraints, and that there is a real risk for many of getting stuck in debt traps.

Low caste people are more likely to have taken loans than others. In the third round of research, 46 percent of low caste people had taken out loans compared to 33 percent of high caste and 30 percent of indigenous Janajatis, a third group included in the study. Low castes are also much more likely to have borrowed in all three rounds of IRM (13%) than is the case for others (9%), or to have borrowed twice (31% versus 25% for Janajatis and 27% for high castes). However, repeat borrowing is not spurring recovery. Across all respondents, those who had borrowed three times were the least likely to report that their livelihoods are recovering. Those who had borrowed three times were also the most likely to have seen decreases in food consumption. Repeated borrowing is also linked to people remaining in shelters. Those who borrowed in both the second and third rounds of the research were more likely to have had to sell assets (9%) compared to those who borrowed once (5%) and those who had not borrowed (2%).

Low caste people also tend to borrow from informal credit providers who charge much higher interest rates. They are almost twice as likely as others to take loans from moneylenders (22% versus 12%) and relatives (33% versus 19% for high castes), both of whom charge far high interest rates than other lenders, and are much less likely to borrow from banks (11% versus 15% for high castes). Furthermore, moneylenders and relatives are also charging low caste people higher interest rates than they charge others (2.7% per month versus 2.1% for moneylenders; 2.4% versus 1.9% for relatives).

All survey respondents identified Dalits as being particularly vulnerable to debt traps. While many struggled to access credit to begin with, those who managed to take secure loans very often had insufficient income to pay interest and pay back their loans. Dalits often said they were worried that they would default but faced little choice but to continue trying to borrow to get by. (Almost one-half said they planned to take more loans in the next three months compared to one-third of high caste people).

Discrimination and disadvantage

Two factors work against the recovery of Dalits and other low caste groups in earthquake-affected districts.

First, discrimination, often engrained in communities despite legal provisions, has had an impact. Tensions between displaced Dalits and upper castes emerged in third-round research in one village focused on access to drinking water from the public water tap. Upper caste respondents said they were unhappy about the presence of Dalits in their areas because they considered them to be “dirty.” To avoid conflict, Dalits started collecting water in the early morning but others were not happy, Dalit children continued to face abuse, and there was pressure for them to return to their unsafe land. The research found that Dalits were more likely than others to be living on the edge of settlements where land was unstable. Similar findings, centered around resettlement and access to water, were found in other villages visited. Many Dalits said that they perceive that aid providers are also discriminating against them. In second-round research, 21 percent of Dalits did not agree that everyone could access aid equally compared to 8 percent of high caste hill people.

Second, material disadvantages that pre-date the earthquakes make recovery much more difficult. Low caste groups have a lower asset base and levels of education. The literacy rate for Dalits is just 18 percent compared to the 48 percent national average. In Barunewshor village in Okhaldhunga district, high levels of illiteracy, a lack of collateral, and an absence of social networks and information on how to approach financial institutions all had an impact. The research found that a lack of education also sometimes made it harder for Dalits to access some aid programs, with them not understanding how to receive aid or able to fill out the forms required.

The Asia Foundation will continue to monitor the situation for Dalits and other groups. The next round of data collection is underway and provisional findings will be available in June 2017.

Funding for IRM is provided by the UK Department for International Development and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

Patrick Barron is regional director for Conflict and Development at The Asia Foundation. He directs the IRM program. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and not those of The Asia Foundation or the project’s funders.

Source: In Asia