By Sher Bano 21 October 2023

The recent decision by Russian lawmakers to withdraw Russia’s ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a significant development that warrants close attention. The CTBT, an international accord established in 1996, has primary objectives aimed at restraining the development of nuclear weapons and mitigating the adverse health and environmental consequences of nuclear tests. Russia’s expedited withdrawal from the CTBT, despite the requirement for two additional readings in its lower parliament, the Duma, raises crucial questions about the motivations behind this decision and its implications for global nuclear disarmament.

The CTBT stands as an international treaty designed to comprehensively ban all forms of nuclear explosions, including those conducted underground and underwater. Its fundamental goals revolve around preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and reducing the health and environmental risks associated with nuclear testing. The treaty arose in response to a turbulent period spanning from 1945 to 1996 when over 2,000 nuclear tests were conducted, primarily by the United States and the Soviet Union, as reported by the United Nations.

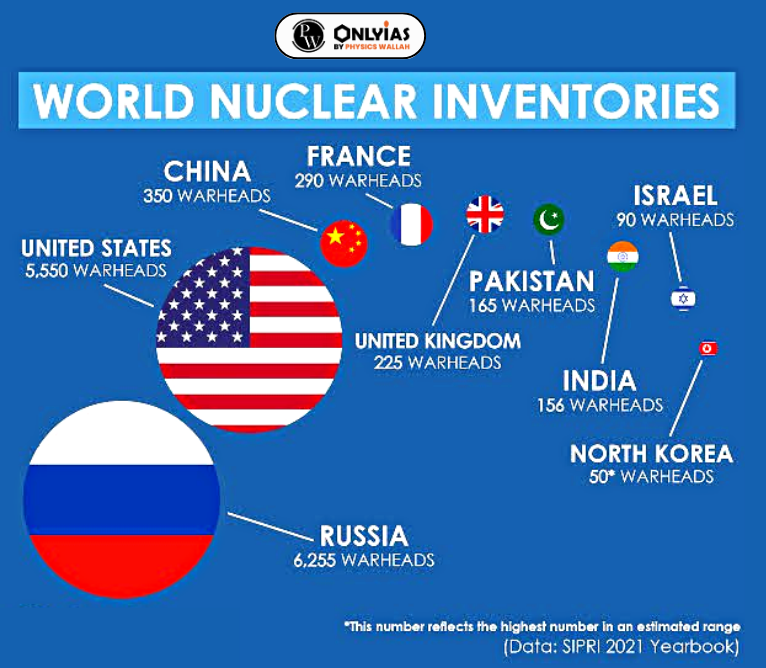

Despite substantial international support for the CTBT, its effectiveness remains hampered by the non-ratification of several key countries, including China, the United States, North Korea, Israel, and Pakistan – all of which possess nuclear weapons. The reluctance of these nations to ratify the treaty has prevented it from coming into full force.

Russia’s decision to withdraw from the CTBT is a development that prompts critical inquiry. Russian President Vladimir Putin has framed this move as a response to “mirror” the position of the United States, without committing to a resumption of nuclear tests. This decision has sparked speculation, with some experts considering it a political maneuver, especially within the context of escalating tensions with the West.

Nikolai Sotov, a Russian nuclear expert and senior fellow at the Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, views this action as Russia’s attempt to send a strong political signal during a period of increasing hostilities. He highlights a shift in Russia’s approach, suggesting that Moscow has become less concerned about potential repercussions from non-constructive negotiations.

Notably, Russia, despite its decision to withdraw its ratification, has expressed its intention to remain a signatory to the CTBT and continue providing data to the global monitoring system. Nevertheless, the act of withdrawal, whether symbolic or strategic, may be perceived as an implicit threat, particularly in the context of ongoing crises, such as the Ukraine conflict.

Turning to the United States, it is worth considering its position regarding the CTBT. While Russia’s decision to withdraw from the treaty has garnered significant attention, it’s essential to recognize the backdrop of the United States’ stance. The U.S. signed the CTBT in 1996 but failed to ratify it following a Senate vote in 1999. At the time, U.S. officials cited concerns about their ability to assess the reliability of their nuclear stockpile without the option of occasional nuclear tests. Additionally, questions were raised about the treaty’s verification mechanisms and its capacity to ensure compliance. Many of these concerns have subsided over time, primarily due to advancements in monitoring systems. However, despite these developments, the United States has shown little inclination to ratify the CTBT. A reluctance to embrace arms control agreements prevails in some segments of U.S. politics, where there is a general wariness about relinquishing sovereignty to international treaties.

The withdrawal of Russia from the CTBT occurs within the broader context of nuclear disarmament challenges. Throughout Russia’s conflict with Ukraine, there have been instances where Russian officials have made nuclear threats, raising concerns about the escalation of nuclear rhetoric. Earlier this year, Russia suspended the New Start Treaty with the United States, which is the last remaining arms control treaty between the two nuclear superpowers. This treaty limits the number of strategic nuclear warheads on both sides.

The concentration of nuclear warheads remains primarily within the arsenals of the United States and Russia. According to the Federation of American Scientists, these two nations possess nearly 90 percent of the world’s nuclear warheads. President Vladimir Putin’s statement, in which he asserts that Russia may use nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack or an attack involving “weapons of mass destruction” and reserves the right to deploy nuclear weapons when its existence is threatened by conventional weapons, underscores the challenges in achieving global nuclear disarmament.

Sotov, who was involved in arms control negotiations in Russia during the late 1980s and early 1990s, believes that Russia is unlikely to resort to using nuclear weapons on the battlefield in Ukraine. However, he expresses concerns that Russia might consider targeting a NATO country if the conflict escalates. Such a scenario illustrates the dangers of an escalation spiral that could unintentionally lead to nuclear conflict.

Importantly, it is imperative to recognize that the CTBT itself does not include a specific provision for “de-ratification” or withdrawal. Instead, the treaty outlines a mechanism for states to withdraw from it, as specified in Article IX. This provision is analogous to the principles articulated in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Article IX of the CTBT states that a State Party may, by providing written notification to the Depositary (the Secretary-General of the United Nations), withdraw from the treaty while offering reasons for the decision.

The process of withdrawal from the CTBT is distinct for each state, as it may involve complex geopolitical, strategic, and domestic considerations. Given the importance of the CTBT in promoting global nuclear disarmament, states contemplating withdrawal should carefully review the treaty’s provisions, its annexes, and any related agreements or resolutions by states parties.