N Sathiya Moorthy 2 April 2018

A possible, easier and less-complicated way for the Centre would have been to approach the SC with the same queries much earlier, before a ground-swell of popular sentiments and consequent political tensions had built up in Tamil Nadu, says N Sathiya Moorthy.

By slating Tamil Nadu’s contempt plea against the Centre for not constituting a Cauvery management board for April 9, and maintaining silence about the Centre’s submissions on the larger issue flowing from the Supreme Court’s ‘final verdict’ of February 16, the three-judge bench headed by CJI Dipak Misra may have cooled hearts, though not the parched lands in the southern state.

Yet, the question still arises, why did the Centre have to bring issues to this point, where the public mood over the past six weeks has forced political parties in the state to announce a series of protests over the coming days, including a DMK-led allies’ black flag demonstration when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visits Chennai on April 11 — and an otherwise ‘accommodative’ AIADMK statement government being left with little political choice but to file the contempt plea in the first place?

If nothing else, anyone with a cursory knowledge of law watching the TV channels’ early coverage of the February 16 verdict would have instantly considered if the term ‘scheme’, mentioned in the ruling, may require a further clarification from the apex court. So should have been the Centre’s law officers, starting with Attorney-General K K Venugopal, a doyen among the nation’s jurists, and two top lawyer-ministers in the Modi Cabinet, Arun Jaitley and Ravi Shankar Prasad.

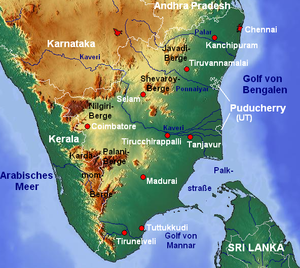

It meant that the Union of India could have filed the petition seeking judicial clarification on the term ‘scheme’ at the first available opportunity — or, at least not long after the Union water resources secretary had met with senior officials from the four riparian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry, as well, where no decision came forth.

The Centre’s current petition specifically mentions this meeting, and explains how Tamil Nadu and Karnataka held divergent views on the word ‘scheme’ — thus rendering any follow-up action on the SC verdict impossible to implement with the cooperation of the states concerned.

What more, the Centre has now sought the SC’s indulgence for grant of three months’ time to implement the verdict, and cite the possibility of law and order situation in Karnataka, where assembly polls are due in the second week of May.

One, the Centre all along knew, that the polls were due by May, and that Cauvery is a sensitive political, social and hence electoral issue in Karnataka, where anti-Tamil riots and arson have taken massive toll, especially in the populous southern districts, including capital Bengaluru.

Two, the Centre’s time demand sounds contradictory as well. After all, any court hearing on its plea for ‘clarification’ could well take time, and maybe go beyond the three months that it has now sought.

It is another matter that in the intervening period, the SC would be having its annual summer vacation, when the Bench of such nature does not ordinarily sit to consider or dispose of petitions/cases of such complexity.

Three, come June, and the new ‘Cauvery season’ would entail the state fresh flows, based on a monthly quota fixed by the tribunal and upheld by the apex court in its February 16 verdict, as well — but that could well be delayed to an indeterminable time, if not indefinitely.

Four, does the Centre’s petition imply that at the end of the three-month extension for Karnataka polls, it would be ready to implement the SC’s February 16 verdict, as may be ‘clarified’ in the coming days/weeks, or even months?

Tamil Nadu, in all probability, and Puducherry, if not Kerala, could well then argue that the Centre’s deadline extension demand tantamounts to giving an ‘undertaking of sorts’ in the matter, at the end of three months and once the required ‘clarification’ from the court was available.

By delaying the obvious, without actually attempting to deny Cauvery waters to Tamil Nadu in any which way, the Centre has still allowed society-induced public tensions to build up in the state over six long weeks, forcing the otherwise ‘competitive’ Dravidian polity in the state, to announce a series of protests — some of them in coalition with political allies, and others in conjunction with others announced by non-political actors like farmers and traders’ organisations.

A possible, easier and less-complicated way for the Centre could have been to approach the SC with the same queries much earlier, before a ground-swell of popular sentiments and consequent political tensions of the ‘Jallikattu protest kind’ from the previous year had built up in Tamil Nadu.

Despite perceptions to the contrary elsewhere, the fact remains, large sections of the people that participated in what mostly remained a peaceful protest for Jallikattu restoration through mid-January all across the state, also owed to the long time lag during the long pre-Pongal holiday season, beginning around Christmas-New Year holidays a full month earlier.

The mood got set even earlier, in October 2016, as an anti-Centre sentiment all across the state, and over the ‘Cauvery dispute’, and not Jallikattu proper, per se. That was when then A-G Mukul Rohatgi told the apex court the judiciary did not have a role in the matter under the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956.

This line of argument had borrowed from the letter of the 1956 law, which said the tribunal had the ultimate authority in river water disputes and Parliament alone was the superior authority in the matter. That is to say, the Act recognised that all river disputes of the kind was quasi-legal and quasi-political, and Parliament would have the non-partisan tribunal award as the technical advice/input in the matter.

However, successive governments, not only at the Centre but even the four riparian states, have acknowledged the Supreme Court’s role in the matter. No MP had raised the incongruity of the situation in Parliament or court, nor had any private citizen, who could have filed a PIL in the apex court, or written to relevant parliamentary committee, or both.

Interestingly, Rohatgi, who had flagged the letter of the law in the apex court one day in October 2016, did not do so earlier — or, even later. But then, the popular sentiment in Tamil Nadu saw in it the ruling BJP’s early efforts to assuage Karnataka’s feelings in the matter, far ahead of the 2018 assembly polls — that too when the state government had not done so, either under the incumbent Congress regime, or the earlier BJP one in the state.

Though the Centre invariably gets heard in such matters first, TN got precedence in the matter possibly because the state’s counsel made an ‘urgent mention’ before the First Bench, headed by CJI Misra on the morning of April 2. It is still most likely that at the hearing, the court may club the two petitions and proceed accordingly.

The Bench, which also included Justices A M Khanwilkar and D Y Chandrachud, orally observed that they understood “Tamil Nadu’s difficulty of not getting water”, and promised that “we will resolve the issue”.

At the same time, CJI Misra clarified orally that the ‘scheme’ mentioned in the February 16 verdict did not stop with the constitution of a management board, but also other mechanisms, too.

To that extent, the Centre’s SC plea now, seeking clarification on the ‘scheme’ part, citing also the conflicting positions taken by Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, may assume further significance.

However, it remains to be seen if the court would ask the Centre to constitute such a mechanism and report back, or do the reverse — now that the very aspect of the ‘final verdict’ too has become a legal issue between the two states.