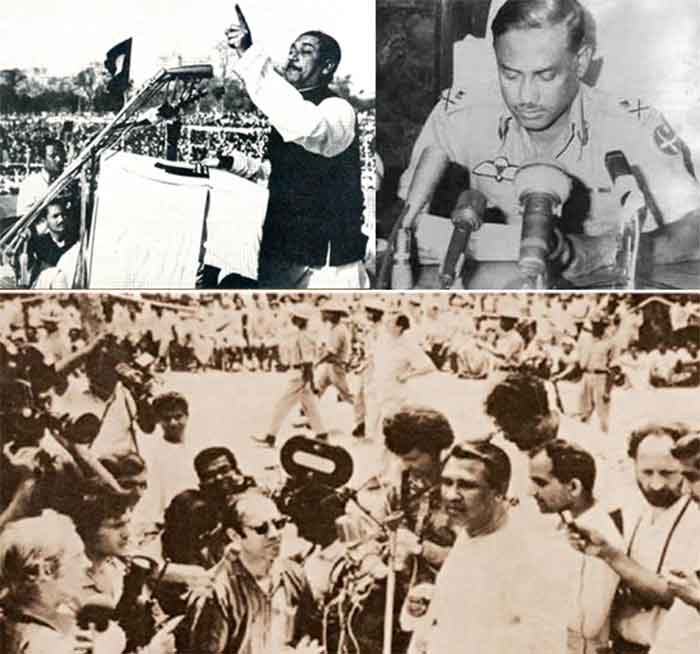

Top Left: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman giving his penultimate speech on 7th of March 1971 at Racecourse Maidan, Dhaka, (then East Pakistan) Bangladesh); Top Right. Major (then) Ziaur Rahan announcing independence of Bangladesh at Kalurghat make-shift radio station in Chittagong, Bangladesh on 27th March, 1971; Bottom: Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed, Prime Minister of Government-in-Exile of Bangladesh formally proclaiming independence of Bangladesh on 10th of April, 1971 in Mujibnagar, a liberated area in Bangladesh

This year on 16th of December, Bangladesh observed 49th anniversary of its independence. On this day in 1971, Bangladesh freedom fighters and the Indian Army jointly defeated Pakistan Army and liberated Bangladesh from the colonial clutches of what was then West Pakistan, now Pakistan.

Bangladesh should be truly proud of its brief existence as an independent state. At the time of independence in 1971, 45% of its 75 million people had no job; did not produce enough food to feed its people and many went hungry; had no industries worth the name and no infrastructure worth a mention; the situation was so dire that Henry Kissinger once rudely branded Bangladesh as an “international basket case.” Mr. Kissinger is still around, and he may eat his humble pie for Bangladesh has since transformed itself from almost nothing to a thriving economy – a shining example of what hard working enterprising people can achieve, in freedom. These days, people in Bangladesh – 165 million of them – are healthier, they eat better and are better educated; their women are freer and empowered. Bangladeshi workers who remitted close to $15.0 billion last year are now an integral part of construction and services sector industries of many parts of the world especially the Middle East.

These are great news and good cause for celebration, together but sadly, unlike 1971 when Bangladeshis fought a vicious liberation war and achieved independence together, they may not be that ‘together’ anymore. In recent years, Bangladesh has evolved as one of the most divided and fractured nations on earth. The issues that divide them are mostly products of self-serving mean politics.

Here, I am highlighting two such issues that I believe continue to divide if not confuse many Bangladeshis. One of these relates to the issue of who made the first call of independence of Bangladesh – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman or Ziaur Rahman? The second issue relates to who between the two leaders – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (SMR) and Ziaur Rahman – contributed most to independence and advancement of Bangladesh?

I am sharing my own perspectives on both issues, not so much to convince people of my position but to encourage informed debate so that we can separate myth from facts and accept facts as facts and move forward, together as one nation.

The Issue of Declaration of independence of Bangladesh in 1971

Let us discuss the issue of declaration of independence of Bangladesh in 1971.

There are several versions of declaration of independence, but most contested among these and especially now, is the view that Sheikh Mujib’s 7th March 1971 Speech is the first declaration of independence. There are also suggestions that in addition to 7th March Speech, SMR also sent out a “telegram” on 26th March 1971 to one of his colleagues informing him of his decision to declare independence of Bangladesh.

Then, there are many that regard Ziaur Rahman’s 27th March 1971 Radio Announcement in Chittagong, as the first call of independence.

Let us discuss.

Sheikh Mujib’s 7th March 1971 Speech

Most Awami Leaguers (currently the ruling party in Bangladesh) firmly argue that Bangabondhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (SMR) – the leader of Awami League (AL) and the Father of the Nation – first declared independence of Bangladesh in his speech on 7th March, 1971 in (the then) East Pakistan.

“The 7th March Speech” – as it is popularly known – was delivered at a mass rally at the then Racecourse Maidan, Dhaka to protest postponement by the Pakistani military junta the inaugural session of the Pakistan National Assembly. Earlier Sheikh Mujib and his Awami League (AL), an exclusively (the then) East Pakistan party had won the national election in Pakistan with majority and thus was looking forward to the first session of the Assembly and form government. SMR himself was hoping to become the Prime Minister of all of Pakistan.

Bhutto, the leader of Peoples’ Party of Pakistan who won majority seats in the West but not in Pakistan did not like the idea of being in opposition. He desperately wanted to be the Prime Minister of Pakistan but AL’s win badly dashed that possibility. Thus him, his other West Pakistani cohorts and his buddies in the Pakistan Army who were not comfortable with the idea of a Bengali ruling Pakistan, put pressure on the then President General Yahya Khan to postpone the inaugural session of the Assembly, which the latter abruptly did without consulting the leader of the wining party, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. This angered Mujib, his party, the Awami League and indeed, (the then) East Pakistanis (now Bangladeshis). (The then) East Pakistanis viewed the postponement of the inaugural session of the National Assembly as an attack on and denial of their legitimate right to rule.

This was the backdrop of the 7th March meeting which, as is evident, was by no means a platform for declaration of independence of Bangladesh, it was a protest rally to condemn the postponement of the inaugural session of the National Assembly and to put pressure on Yahya to reconvene the Assembly the soonest. Accordingly, in the meeting SMR made demands to withdraw Martial Law and transfer power to the wining party, the Awami League though SMR, who was an astute politician also sensed the public mood and thus in his speech he uttered these words as well, “This time our struggle is for liberation; our struggle is for independence…”

Some – mainly AL – interpret these words as declaration of independence without realizing that these words were mere conjectures and not the intent, not at the time. Real intent of the rally was to put pressure on Yahya to transfer power and had Yahya accepted SMR’s conditions and re-convened National Assembly promptly and transferred power to the elected representatives, Sheikh Mujib would have been the Prime Minister of Pakistan and not Bangladesh. However, as SMR never trusted Pakistanis fully, he also used the protest meeting to warn (the then) East Pakistanis against future attacks from the Pakistan establishment and accordingly, asked them to prepare and resist such attacks with ‘whatever means you manage to lay your hands on.’

Therefore, and to me at least, Mujib’s 7th March 1971 Speech at the Racecourse Maidan was not a declaration of independence per se. It was a warning to the Pakistani establishment of the danger of delay in transfer of power and at the same time, alerted the (the then) East Pakistanis against future assaults.

What followed is history – in the aftermath of the meeting Yahya invited SMR and his colleagues for talks (which was nothing but a decoy to prepare for further attack), abruptly abandoned talk and viciously cracked down on (the then) East Pakistanis on the night of 25th March 1971. People resisted and turned what until this point was a movement for autonomy into an armed uprising for liberation. Therefore, the 7th March Speech was not a call for independence as such but a speech that it nonetheless mobilised and motivated people to resist Pakistani attack and fight back and turned, by default than by design, the autonomy demand into a liberation war.

The other claim that SMR sent out a telegram in the early hours of 26th of March 1971 to one of his colleagues informing him of his decision of independence of Bangladesh is yet to be validated with credible evidence.

Zia’s Radio Announcement

The first human voice that explicitly and publicly announced independence of Bangladesh came through a radio announcement on 27th March 1971, two days after the 25th March Pakistan Army crackdown, through the voice of the then Major Ziaur Rahman in Chittagong. Through this announcement Zia signalled and made it widely known that he and fellow Bengali officers of the Pakistan army had rebelled and commenced a war of liberation against the Pakistan state.

Zia’s Announcement at the Kalurghat (Chittagong) makeshift Radio Station (I myself heard that announcement) also mentioned for the first time, “Bangladesh” as a distinct national entity and in an official capacity of sort, In his Announcement Zia also affirmed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the leader.

Tajuddin’s Proclamation of Independence

Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed, the Prime Minister of the Bangladesh Government-in-Exile made formal Proclamation of Independence of Bangladesh on April 10, 1971 at Mujibnagar, a liberated area in the then occupied East Pakistan.

Where do we go from here?

So where do all these different claims of “declaration” of independence lead us?

Not that it matters but since this is one of the issues that continues to divide us and confuse us, it is important that we get to the bottom of it – so, who made the first call?

Initially, there was no controversy nor any competition involving the issue of announcement of independence of Bangladesh – each was viewed and regarded on its own merit and context.

Controversy of the “declaration” issue started in more earnest in late seventies, from the time the newly formed Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) made an overkill to glorify and legitimise its army general-turned-politician leader and freedom fighter, Zia as the new alternative leader in Bangladesh. BNP portrayed Zia as a greater hero mainly because unlike its rival, AL that has had long history and significant political capital, the new party has had none of these, at its initial stage. Thus, the party needed to build political capital to prove its relevance vis-a-vis AL and the only asset BNP had at the time was Zia and his liberation war credentials especially his 27th March radio announcement of independence of Bangladesh. They thus went on an overdrive and used the ‘Announcement’ to kill two birds with one stone – devalue SMR and bolster Zia and in the process, glorify BNP and sideline AL. This possibly was also the beginning of acrimonious politics in Bangladesh that continues to divide the nation along party lines to this day.

So, who made the first announcement of independence of Bangladesh?

From the facts that I have gathered so far and based on what I myself have seen or witnessed; I draw following conclusions on the issue of declaration of independence of Bangladesh:

- Sheikh Mujib’s 7th March Speech was not a declaration of independence per se. However, the Speech inspired and mobilised (the hen) East Pakistanis to resist and fight against Pakistani assaults. As a result, when Pakistan Army cracked down on 25th March 1971, people refused to be cowed down. Instead, entire (the then) East Pakistan resisted and opted for liberation war, revealing Speech’s formidable contribution in mobilizing, inspiring and committing (the then) East Pakistanis to fight back and achieve independence.

- Ziaur Rahman’s 27th March radio announcement was indeed the first known call of independence of Bangladesh though his personal participation in the Announcement was more incidental than instrumental in the sense that, had any other rebelling Bengali officer other than Zia were present at the spot at the time, would have done the same. Therefore, there is nothing special about Zia making the announcement though his defiant, confident and determined voice of rebellion worked like a magic, signalled the beginning of the liberation war and inspired an entire nation at a time when things looked grim and dire.

- Tajuddin’s 10th April 1971 Proclamation of Independence is the actual formal internationally recognised declaration of independence of Bangladesh.

Thus, it is evident that each of these announcements has had its own context, merit and purpose and that each had its fair share of mobilising and motivating (the then) East Pakistanis to commit to and work towards independence of Bangladesh – thus each has to be valued equally. However, so far as the issue of official announcement of independence of Bangladesh is concerned, an announcement that gave the independence movement a formal framework and global visibility, my vote is for Tajuddin’s April 10, 1971 Proclamation of Independence in Mujibnagar.

Mujib/Zia Debate

Another issue that divides Bangladeshis bitterly involves rival and contested claims of who between Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Ziaur Rahman was a greater leader. Both AL and BNP supporters make frenzied efforts to pit one against the other and in order to glorify one, they tend to demonize the other. This is utterly disgraceful because both SMR and Zia made transformational interventions that contributed to firstly, creation and later advancement of Bangladesh. While SMR has been pivotal in the creation of Bangladesh, Zia advanced Bangladesh developmentally. At the same time, both made mistakes as well.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

My personal view and I believe most people would agree with me that comparing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman with any other leader of Bangladesh – save and except Maulana Bhashani – is irresponsible. Without Sheikh Mujib there would be no Bangladesh and most importantly, without Sheikh Mujib there would also be no Ziaur Rahman.

Sheikh Mujib’s political career began under the tutelage of Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy, the Muslim League leader of the undivided Bengal. SMR began as League activist and fought for creation of a Muslim majority state, Pakistan, in the sub-continent. However, after establishment of Pakistan in 1947, a country that was physically divided between two wings, East and West and India in-between and where West treated East with disdain, SMR quickly shifted his political agenda and made fight for maximum autonomy of (the then) East Pakistan his lifelong mission. In his fight for autonomy, he almost single-handedly mobilised East Pakistanis to stand against West Pakistani injustices, a fight that at the end motivated (the then) East Pakistanis to face-up, resist, separate and liberate East from the West and establish independent state of Bangladesh. Every Bangladeshi, men, women and children ought to acknowledge this and bow their heads to SMR for the contributions and sacrifices he made to wage a movement that at the end and thanks to Pakistan’s persistent intransigencies, eventuated in the establishment of an independent state – Bangladesh.

However, SMR’s detractors argue that by not joining the liberation war personally and by courting arrest on the night of 25th March 1971, the night of violent attack on his people by the Pakistanis and by sitting out the entire war period in a Pakistani jail, he betrayed the nation. I disagree. I believe that courting arrest was the best thing that SMR could do at the time. Indeed, had he fled and joined the liberation war, Pakistan Army would have let hell descend on the entire nation, much worse than what they did; and secondly, Bangladesh movement itself would have lost its moral credibility in the eyes of the international community as many would have treated the whole thing an India inspired secessionist plot. Furthermore, had SMR fled to India and joined the liberation war things might not have been as smooth as were under the less charismatic but vastly pragmatic Tajuddin. Moreover, as SMR was a strong nationalist it is unlikely that he would have agreed to all of India’s dictates especially India’s patronising attitude with the result that he would have been either sidelined (this is what Indians did to Maulana Bhashani) or something much worse.

Thus, we should never view SMR’s absence from the liberation war as “betrayal” and devalue his unparalleled and unquestionable contributions in the creation of Bangladesh.

However, this is not to say that SMR did not make mistakes. His role as a leader in post independent Bangladesh was anything but inspiring. Many things that happened under his watch – rigging of elections, turning a parliamentary democratic system into one-party rule, extra-judicial killing as an officially endorsed strategy to tackle political dissidents, mishandling of a famine etc. etc. – haunt and plague Bangladesh to this day.

Another issue that undermined SMR’s credibility as an administrator was corruption. Although SMR himself was never corrupt and never approved of corruption, his emotional attachment to his party colleagues who indulged in acts of wanton corruption, restrained him from prosecting and punishing corrupt elements of his party. This was unfortunate.

In sum, when it comes to the idea of Bangladesh, none but Sheikh Mujib and Sheikh Mujib alone is the leader who stands head and shoulder above all and thus be acknowledged as such, he is the Father of the Nation. However, it is also important to appreciate that SMR was not without faults – he did make mistakes. Due acknowledgement of his good and bad deeds makes SMR a human, which he was.

Ziaur Rahman

Some of the detractors of Ziaur Rahman who claim that he, a valiant freedom fighter, was a “Razakar” and a “Pakistani agent” reveal only their own dysfunctional state of mind. Ziaur Rahman’s role in the liberation war for which Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation himself honoured him with “Bir Bikram” is well documented. My position on Zia’s participation in the liberation war is that he was indeed a valiant freedom fighter but his contributions as a freedom fighter are no more than many other Army and non-army fighters that joined the liberation war. My assessment of Zia is not about his war accomplishments which no doubt are noteworthy but more about his role in post-independent Bangladesh especially after his assumption of state authority in 1977.

Ziaur Rahman came to the helm after several coups and countercoups that began with the August 15, 1975 coup that killed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and toppled his BAKSAL government. August 15 Coup did not bring Zia to power though he was made the army chief by the incumbent President Khandaker Musaque Ahmed, an Awami Leaguer. Therefore, claim of many Awami Leaguers that Zia was the main beneficiary of the coup is not correct. Zia was a product and not an initiator of any of the events that catapulted him to power.

Many Awami Leaguers also claim that Ziaur Rahman had a hand in the August 15, 1975 coup. So far, no concrete proof has been presented to substantiate these claims. In fact, if there is one person in the army who ought to have been made accountable for the August 1975 coup and the death of the Father of the Nation and his family members, it ought to have been General Shafiullah, the then army chief. As chief of army it should have been his job to detect the coup plot and stop it from taking place. More importantly, during the coup itself, it should have been him as the army chief who should have acted and averted the coup and saved the life of his commander in chief, President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Shafiullah did not do any of these and what is intriguing is that despite these gross lapses, AL, a party that suffered most by Shafiullah’s negligence rewarded him by making him a member of their party, gave him nomination to contest an election and got him elected as a Member of Parliament. This is baffling.

Khandoker Mustaque, a close friend and colleague of SMR who many believe had a hand in the coup became the President after the coup and thus was the first beneficiary of the August 15, 1975 change-over. It is Mustaque who sacked General Shafiullah and made Shafiullah’s deputy, Zia the new army chief. However, all these were short-lived.

Soon led by General Khaled Musharraf, a counter coup on 3rd November 1975 toppled Mustaque government, sacked Zia and put him under house arrest. In the second coup General Khaled Musharraf was the beneficiary and Zia, a casualty of the coup. However, like the first coup, the second coup was also short-lived.

Soon after and led by Col. Taher another coup took place on November 7, 1975 that ended General Khaled Musharraf’s weeklong tenure and the mutineers also killed Khaled Musharraf and several of his coup colleagues.

November 7 coup leaders brought back Zia out of internment and re-installed him as the Army Chief, with Justice Sayem, the immediate past retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, as President and Chief Martial Administrator. Zia was made one of the three Deputy Chief Martial Law Administrators. Here also, Zia was neither an immediate nor an intended beneficiary.

However, after several bouts of internal shuffling Zia finally took over the government, as President, in April 1977 and formed his party, BNP.

After becoming the President Zia took few decisive actions that transformed Bangladesh – first, he brought back discipline in the army which thanks to coup and countercoup was in complete disarray with chain of command totally broken; also took steps to steady the state which was on the verge of collapse; dismantled SMR’s ill-conceived one-party BAKSAL system and re-introduced multi-party politics; established strict management accountability in the government; reformed the economy, and laid the foundations of growth that have since propelled Bangladesh’s development to where it is today. Furthermore, Zia expanded diplomatic relations and forged closer ties with Islamic countries that have since opened job opportunities for millions of unemployed Bangladeshis in the Middle East and counting. He also modernized and reformed agriculture and most importantly, instilled among the people of Bangladesh a new sense of Bangladeshi nationalism, oriented to Bangladesh’s own history, culture and values.

However, like his famous predecessor, SMR, Ziaur Rahman also had his faults. For example, he himself was not corrupt but during his time, corruption became institutionalised. His worst misstep was that he rehabilitated and re-incorporated anti-liberation forces like Islamic fundamentalist anti-liberation party, Jamaati Islami into politics of the country. True, in democracy every idea and ideologies have equal right to participate in politics of a country but so far as Jamaati Islami is concerned its role in Bangladesh needed to be seen in a different context. Indeed, given that Jamaati Islami never acknowledged nor apologised for their active collaboration with Pakistan and crimes they committed during the liberation war, this party’s incorporation by Zia might have been politically a shrewd move but was morally totally inappropriate. Furthermore, as Zia’s tenure was riddled with coups and counter coups within the armed forces itself, many ordinary soldiers – some claimed to be innocent – were tried in Kangaroo courts and executed. This is reprehensible.

These contradictions caught up with Zia eventually and in 1981, he was killed in an army coup in the very town, Chittagong, where he rebelled and made the first famous declaration of independence of Bangladesh, just a decade ago.

Moving from controversies to consensus

It is obvious that both SMR and Zia contributed immensely to the creation and advancement of Bangladesh – while Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the indisputable Father of the Nation, Ziaur Rahman can easily be called the Father of Development Bangladesh. Notwithstanding and as is evident, both made mistakes.

So, where do these contradictory attributes of our heroes take us? Should we only highlight their positives and ignore negatives? More importantly, in order to idolise one, should we demonize the other? The answer is – no, we should not but then how do we reconcile their good with their bad and still respect them for what they did for us and the country?

I got the answer to the conundrum from a recent account of a BBC journalist who travelled through China, asking following questions to many young Chinese regarding Mao Zedong, “How do you evaluate Chairman Mao?” Majority answered, “He did both good and bad.” The BBC journalist asked, “What are the good and bad things of Mao?”. They answered, “Chairman Mao united the country and restored China’s sovereignty, but his Cultural Revolution destroyed the economy and millions died of starvation.” “So, how do you reconcile Chairman Mao’s good with bad” asked the BBC journalist and the answer, “We try and acknowledge both – Mao’s good inspires us and reminds us the value of unity and importance of sovereignty; his bad has taught us what not to do.” Precisely!

The author is an academic and former senior policy manager of the United Nations

The article appeared in the Countercurrents on 21 December 2020