NEERAJ SINGH MANHAS

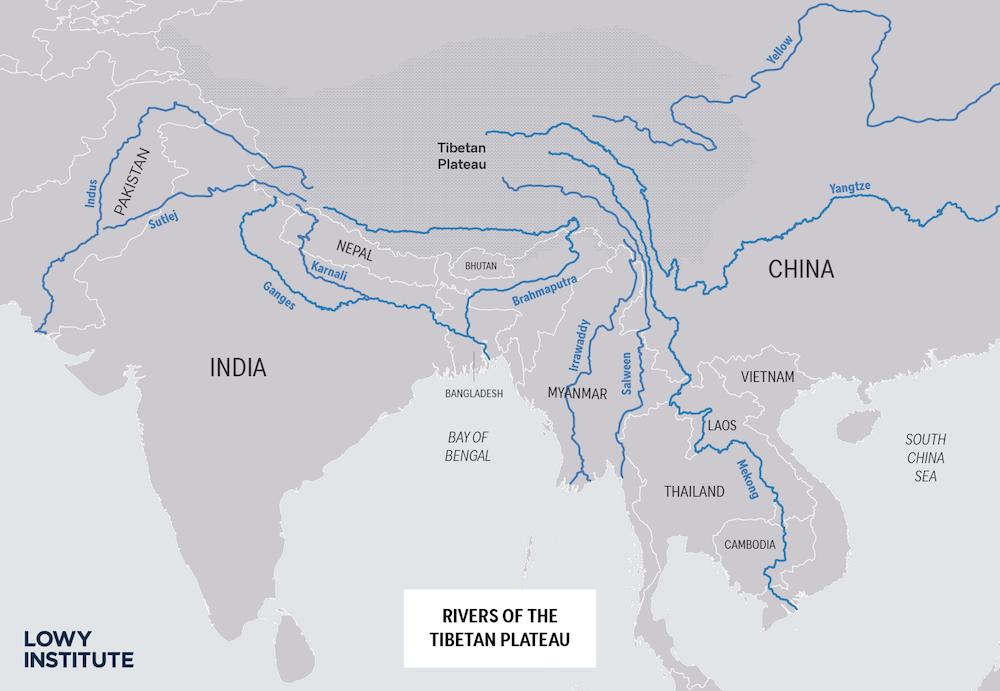

A proposed dam in China’s Medog county would be the world’s largest hydroelectric project, surpassing even China’s Three Gorges Dam, which is currently the largest dam in the world. The Yarlung Tsangpo, originating from the Tibetan Plateau, flows into India as the Brahmaputra River and continues into Bangladesh as the Jamuna. And not surprisingly, China’s ambition has alarmed downstream countries.

Reports suggest that this dam could significantly alter water flow patterns, affecting millions of people who depend on the river for agriculture, fisheries, and daily consumption. According to official Chinese sources, the project aims to harness Tibet’s rich hydropower potential while reducing reliance on coal and aligns with its green energy goals and carbon neutrality targets by 2060. This dam, projected to generate 60 gigawatts (GW) of power, with a cost of $137 billion, would have almost three times the capacity of the Three Gorges Dam.

India, which relies heavily on the Brahmaputra River, is likely to face serious hydrological challenges. The river provides water to Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and other northeastern states, supporting nearly 130 million people and six million hectares of farmland. If China diverts or controls the river’s flow, India could experience unpredictable floods during monsoon seasons and severe droughts in dry months. A 2024 study published in the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs warned that China could manipulate water releases, potentially affecting India’s economic and strategic interests. Indian hydrologists have expressed concerns that sediment flow, crucial for agriculture, may be blocked by the dam, reducing soil fertility in the northeastern plains.

As the Brahmaputra transforms into the Jamuna River in Bangladesh, its flow is crucial for more than 160 million people. Bangladesh, already facing acute water stress and climate change challenges, depends on the river for agriculture (55 per cent of its irrigation needs), drinking water, and fisheries. The dam in Medog county may further reduce water availability, especially during non-monsoon months, leading to a decline in crop yields and an increase in salinity intrusion in coastal areas. A 2022 report by the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change estimated that even a five per cent reduction in Brahmaputra flow could lead to a 15 per cent drop in agricultural output in certain regions. If China retains more water upstream during the dry season, Bangladesh’s economy could suffer significant losses, exacerbating food insecurity and migration issues.

The construction of the Medog dam poses substantial ecological risks. Large-scale infrastructure projects in seismically active regions such as the Himalayas increase the likelihood of landslides and earthquakes. The Yarlung Tsangpo Basin is highly sensitive, and past studies indicate that dam construction in such areas disrupts fragile ecosystems. A 2023 study published in the Advancing Earth and Space Sciences journal indicated that large dams alter sediment transport, leading to riverbed degradation and a decline in fish populations. The Brahmaputra and Jamuna rivers support nearly 218 fish species, including economically important ones like Hilsa and Mahseer. Disrupting their migratory patterns will threaten regional fisheries, impacting the livelihoods of two million fishermen in India and Bangladesh.

India and Bangladesh must push for legally binding water-sharing agreements with China to ensure transparency and equitable water distribution.

China’s unilateral decision to build the Medog dam, without consulting downstream nations, raises geopolitical tensions in South Asia. The lack of a water-sharing treaty between China, India, and Bangladesh further exacerbates the situation. While China has provided hydrological data to India since 2006 and to Bangladesh since 2008, experts argue that such data-sharing agreements are insufficient in preventing potential water conflicts. India has expressed concerns about China’s control over transboundary rivers, with policymakers advocating for stronger diplomatic and strategic countermeasures.

In 2021, India proposed the Lower Siang Dam (11,000 MW) in Arunachal Pradesh as a countermeasure to regulate Brahmaputra’s water flow. However, this project has faced environmental and local opposition, delaying its implementation. Bangladesh, on the other hand, is highly dependent on regional cooperation. Experts suggest that a trilateral water-sharing agreement between China, India, and Bangladesh could mitigate potential conflicts and promote sustainable river management.

The potential risks for the proposed Medog dam – ranging from water shortages and agricultural losses to environmental degradation and geopolitical tensions – demand urgent regional dialogue and cooperation. India and Bangladesh must push for legally binding water-sharing agreements with China to ensure transparency and equitable water distribution. Additionally, international mediation, possibly under the UN Water Convention of 1997, could provide a framework for dispute resolution.

With climate change already exacerbating water security issues, South Asia must prioritise sustainable river management and regional cooperation to prevent future conflicts over one of the most critical resources.

source : lowyinstitute