The “road to nowhere” is now heading for a cliff.

China’s famed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is teetering on disaster, and could lead to a global domino effect where one country after another gets knocked down by economic failure.

Friend and colleague Chris Snow drew my attention to a podcast from Joe Blogs in which he explored the dangers. Blogs bases his findings on work by AidData, which has released a new, 400-plus page report — Belt and Road Reboot: Beijing’s Bid to De-Risk Its Global Infrastructure Initiative.

The “Belt” refers to the historic overland routes through central Asia that used to link China with the West; “Road” refers to the sea routes of the same period that linked South Asia to the Middle East and Africa.

The BRI is the biggest single overseas investment project that any country has made in the past 20 years. 155 countries have signed up for the program, and they include 75% of the world’s population and more than half of the world’s GDP.

These countries have signed up for Chinese loans to construct massive infrastructure improvements. There has been ongoing concern that they will not be able to pay back the loans, which has consequences, but lately another and more desperate concern has arisen: can China afford to keep the construction going until the projects are finished?

When the BRI was started, bets were made on whether the projects were smart and/or whether they would be profitable.

No one considered the possibility that China would (economically) drive off a cliff.

Now China is having a Black Swan moment — a situation that was completely unforeseen.

China’s own economy is tanking.

Outside investment in China has dropped 95% — a response to China’s clumsy handling of the Covid crises as well as worker riots and the hostility brought on by the war in Ukraine.

CNN Business says “Consumer prices [in China] are falling, a real estate crisis is deepening and exports are in a slump. Unemployment among youth has gotten so bad the government has stopped publishing the data.”

The real estate market — the major source of investment for Chinese consumers — has seen a crash that is so bad that a major homebuilder and a prominent investment company have missed payments to their investors. Some 65 million homes sit empty — victims of the real estate drive that underlay the country’s economy.

China’s GDP targets are likely to be missed.

Which is really hard to do, because they are a fiction anyway. Its international lending and grant-giving activities remain shrouded in secrecy.

Other nations look at Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as an output: the result of things going right in your economy. China looks on GDP as a measurement declared by the government that at all levels of society must strive to make happen.

So when you hear that “China’s GDP grew by X% in the past year”, bear in mind that you are hearing “China’s GDP TARGET was X% (and of course the government said it reached its target).”

China’s ‘amazing’ GDP growth has been a sham for decades. One US prof estimates — based on NASA satellite imaging data about the consumption of electricity — that China’s GDP numbers are over-estimated by one-third.

Authoritarian regimes routinely respond to bad news by lying, and when the GDP numbers don’t seem even feasible to announce, they simply do not release economic numbers when they don’t tell the happy success story that Beijing wants the world to hear. And China has stopped releasing the numbers.

China’s economy is not going to overtake America’s because it can’t. Its labour costs are higher than competing regional neighbors, its social safety nets (ironically for a socialist country) are non-existent, and its finances are a fantasy.

Longer-term, the demographics are a nightmare. In the coming two decades China will lose a number of workers equal to the entire population of Brazil. The under-14 population is also going to fall, so there will be few people to replace the workers. Because of government policy — the one-child population control regulation — it has a dearth of women, and the women it does have seem to be disinclined to want children (two-thirds have expressed “low birth desire”). Fertility rates in Beijing and Shanghai have fallen to the lowest in the world.

China also has one of the fast-growing “debt burdens” in the world — the amount of money invested in projects whose economic benefits are less than their cost. Total debt as a share of GDP is now 295% in China, compared with 257% in the U.S.

Outside companies are overwhelmingly reducing their exposure in China. They are “re-globalizing” and spreading their operations to Vietnam, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and elsewhere.

Now, on top of this mess comes the BRI.

When it was started 20 years ago, the above factors had not clearly emerged.

The problem China has now is that the BRI client countries have not been very stable, and the money flows that could cover the interest payments alone have been falling behind…let alone attempt to pay down the loans themselves.

At one time, China could afford to keep supporting all of these projects. Now however China’s economy has chugged to a halt. Exports are falling and Chinese companies are in ‘contraction’ mode.

The Yuan, therefore, has fallen in value, which makes matters worse.

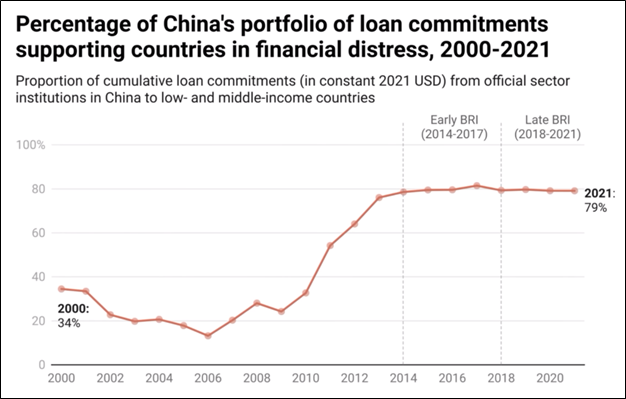

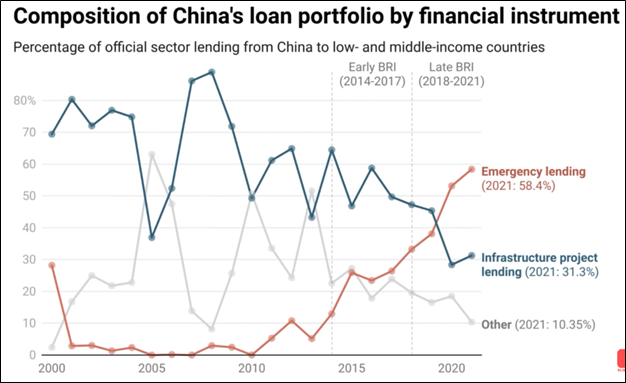

And at this point in its development BRI projects are largely in a semi-complete stage. The only thing one can do with the projects at this time is keep financing them until they are complete and are generating a return on investment. Almost 80% of the loans have been to countries that are in financial distress. China did very little in the way of financial analysis before plunging ahead with these projects. On top of that, the Chinese financing is not a grant, it is a loan, which means that the amount that the countries need to pay back is becoming an even greater burden for them…and a less likely prospect that they will pay back the loan. By the time the projects are finished, control of the assets will be in Chinese hands.

This means that in 146 countries, control over their power stations, roads, and other infrastructure could soon run by the Chinese.

China could be in a position to demand that these countries increase their sales to China and to use Chinese Yuan as the global currency. These aspects of political control are of global impact.

But China has another problem as well. The $1.3-trillion that is already invested by China is like an anchor chain looped around its ankle…it is money that has already been spent and China has to keep following the anchor down until the project are completed…until bottom is reached. China needs to continue investing at a time when their own economy is shrinking and the money would be better invested back in China.

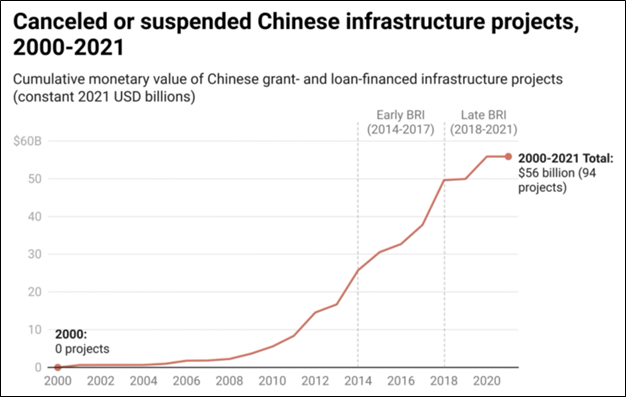

If China does not have the financial reserve to finish the projects, they will become uncompleted ruins for later generations to gawk at. There is not much value in half of an electrical dam.

This means that China’s investment thus far could be completely worthless.

Further bad news: China will soon face higher levels of competition in the global infrastructure finance market due to the US Build Back Better World Initiative and the E.U.’s recently announced Global Gateway Initiative.

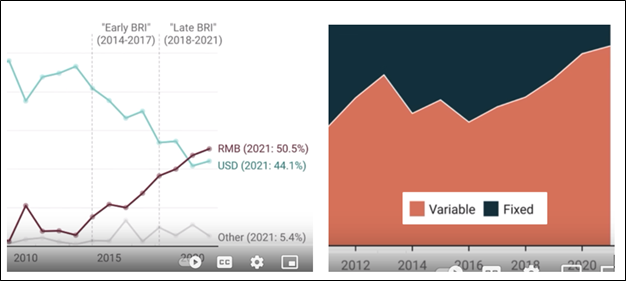

China has been increasing the loan currency lending being done in Chinese RMB (Yuan) to provide for debtor nations to pay back through increased trade with China, It has also been putting more into variable interest rates, so that China will be able to set the ongoing terms of engagement.

From a borrower’s point of view, having a variable rate is a bad thing, because it is set by the lender. China also charges ‘penalty rates’, which have now gone to 1.8%. This weakens a borrower’s ability to pay back the debt even more.

Host countries also run an increasing risk of having their collateral — e.g. a newly-constructed port — taken over by China if payments fall behind. China, for example, now has full control and ownership over a major port in Sri Lanka. This is giving heartburn to India, across the water, because China could choose to set up a military base in Sri Lanka.

The question of where the cash will come from that will enable the borrowing countries to repay the debt makes an assumption: that the projects have been completed on-time and are therefore generating the revenues that were anticipated. Now, 44% of all loans have reached their repayment date, and by 2050 all of the loan amounts will be due. China will be the only country that they can deal with to reschedule the loans.

Chinese creditors lent to high-risk countries (79%). Whether they meant to do that or not is unknown; when the BRI was being planned, China’s economy was relatively healthful if fictional.

Chinese state-owned creditors went on a lending spree, issuing thousands of loans for big-ticket infrastructure projects spread across the developing world. However, they did so without strong risk management guardrails in place. They lent to borrowers with bad credit ratings or no credit ratings (like Laos, Tajikistan, Zambia, South Sudan, Suriname, Zimbabwe, Pakistan, and Argentina); banked on borrowers being able to repay loans with the cash proceeds from natural resource exports (like Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Ecuador, Venezuela, Congo-Brazzaville, and Turkmenistan); and issued dollar- and euro-denominated loans to countries (like Russia, Belarus, Myanmar, Sudan, Iran, and Cuba) that would later be unable to transact in those currencies due to international sanctions.

Grown-ups did this.

China stepped out into the world with great fanfare, confident that it could buy its way to global influence and gratitude. Now, public approval rates for the BRI according to the World Gallop Poll are at 32%. China’s desire to use its financial leverage to buy alignment with its policies has fallen flat: governing elites in BRI participant countries are taking foreign policy positions that are increasingly out of alignment with those of China.

When a promise like BRI goes sour, politicians and press remember.

Beijing’s losses in the BRI program outnumbered its wins — by a significant margin.

If you were looking for a perfect example of ‘failed public policy’ you would not have to go further than China’s BRI program.

$1.73-trillion, wasted.

How could anyone have foreseen that economic planners from a state-run economy where the government makes up numbers for prices and wages, would turn out so badly?

Shocking, I know.

This could be a good opening for some “Go Fund Me” projects.

In the meantime, I’ve got a dam to sell you.

But instead of just watching this slow-motion crash in horror from the sidelines, there is another approach for the West.

If we stopped looking at China as an opponent, and looked at it as a project on an evolutionary path to Western democracy, we could step in and offer to help finish these BRI efforts.

The West has the financial resources. know-how and capacity to help out as equal partners. Just as important, we have the technical skill to bring these projects to completion on time.

If China would agree to re-orient the program to become a global infrastructure initiative, it would work out well for everyone.

And it would probably have side-effects for places like Taiwan, which would no doubt find itself off China’s “To Do” list…at least for the imminent future.

China could be a partner, not an enemy.

Ask Elon Musk.

OK, bad example. But you get what I mean.

Chinese executives are smart, open and ready to trade, in my experience. If we gave the country a chance, the entire structure would have to start moving our way.

It’s worth considering.