A change in international institutions is inevitable but the continued protection of human rights still a key concern

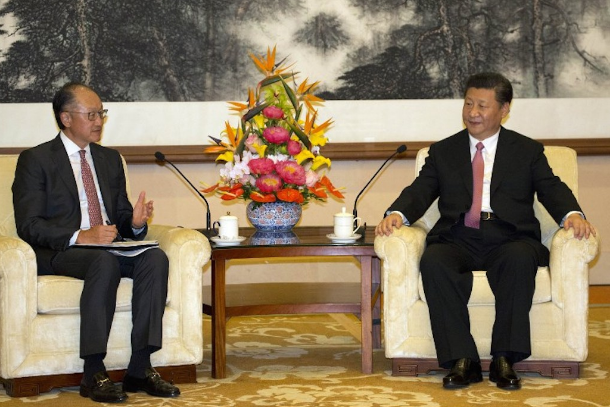

New sheriff in town: China’s President Xi Jinping (right) meets with World Bank President Jim Yong Kim at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing on July 16. (Photo by Ng Han Guan/AFP)

China’s ruling Communist Party concluded its Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs in June, only the second such event since Xi Jinping became president in 2012.

“These meetings are not everyday affairs,” said former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd, who now serves as head of the Asia Society Policy Institute.

“They are the clearest expression of how the leadership sees China’s place in the world, but they tell the world much about China as well,” added the noted Sinologist, giving a typically clear-eyed analysis of the conference.

The key takeaway from the conference is that China has its own ideas about what a new international order should look like, and Asia Pacific is already feeling the effects of this.

While post-World War II institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have lost some of their luster and become something of a mess, the same cannot be said of many developing nations.

India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and Iran — the list of fast-evolving countries that are growing in wealth, population and influence keeps getting longer.

More change is inevitable. China is determined to lead the charge and it is in a position to do just that given its growing clout in the region and the world.

Since the first iteration of last month’s conference, back in 2014, Xi has pushed the button on his Belt and Road Initiative, pumping money in the form of loans (not aid) into Southeast, South and Central Asia as well as the Pacific.

Now the project is moving further afield, into the Middle East and Eastern Europe. China has also initiated its first multilateral institution in the guise of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

This is already making waves, with $4.2 billion invested in projects and funds last year alone. That marks a huge leg up from one year earlier, the Asia-centric bank’s first year of operation.

Meanwhile, in late June the AIIB held an annual meeting in Mumbai and committed to investing $100 million in India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund. The bank also inked a memorandum of understanding with the Islamic Development Bank to co-finance certain projects.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said later that he wants the AIIB to expand its overall financing from $4 billion to $40 billion by 2020 — and climb further to $100 billion by 2025.

Yet the effect of this splurge has already seen China emasculate ASEAN, which now no longer speaks with one voice as it cannot agree on joint communiques if China is involved.

In his speech at last month’s conference, Xi, who has reasserted the primacy of the Party in his almost six years as its leader, said China can “lead the reform of the global governance system [based on] the concepts of fairness and justice.”

He specifically pointed to “multipolar” reform, which as Rudd pointed out implied a diminished role for the U.S. and Western countries in general, which together now form about 10 percent of the world’s population.

China’s foreign policy meeting last month was nothing if not timely.

The U.S.-NATO alliance is in a state of disarray and U.S. foreign policy under President Donald Trump has become an unholy mess as he cozies up to Moscow, and went through the motions of a summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in July that many critics saw as pointless.

It even prompted the following headline from The New Yorker writer Susan B. Glasser on July 19: “No way to run a superpower”: The Trump-Putin summit and the death of American Foreign Policy.”

Trump had already sown more divisions earlier by fracturing Washington’s relationship with other G7 members at a conference in Canada, a development Beijing may not have been unhappy to see.

The U.S. is effectively, and perhaps unwittingly, helping China to achieve its goal of building a new world order, part of which involves Beijing exploiting the growing rift between Washington and Brussels.

China and the European Union held their annual summit in Beijing on July 16, which produced some interesting developments.

“I have always been a strong believer in the potential of the E.U.-China partnership,” said Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission. “And in today’s world that partnership is more important than ever before. Our cooperation simply makes sense.”

The turmoil created by Trump comes as he launches deeper into a trade war with China, thus driving traditional allies of the U.S. even closer to China.

Meanwhile, at a press conference on July 18, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Hua Chunying pulled back the veil and issued remarks that were uncharacteristically revealing of the Party’s thoughts.

“The U.S. trade war is not just with China but with the rest of the world,” he said. “By regarding the rest of the world as adversaries, the U.S. has dragged the entire global economy into a place of danger.”

So this moment provides a rare opportunity for China to gather allies, at least economically, and strengthen its position in building a new world order.

But perhaps the most daunting prospect of all this change is China’s stance on human rights and religious persecution, given Xi’s current program that aims to stifle Christianity and Islam in his own country.

One example of how China is taking advantage of this situation is in its warming ties with Myanmar — a key local market for its ambitious arms makers — while other nations shun it over the alleged “ethnic cleansing” of Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state at the hands of the military.

As is the case, generally, with the rise of the largely undemocratic developing world, China is now making its voice heard and taking no prisoners along the way.

As new institutions are born and old ones such as the WTO are looking at being reshaped to survive this new era, moves to protect human rights, social justice and the billions of poor and suppressed around the world from their tormentors — of which China stands as “Example A” — are becoming more important than ever.