Bold Chinese plan for economic ‘corridor’ changes game for the civil war in Myanmar’s Kachin and northern Shan states

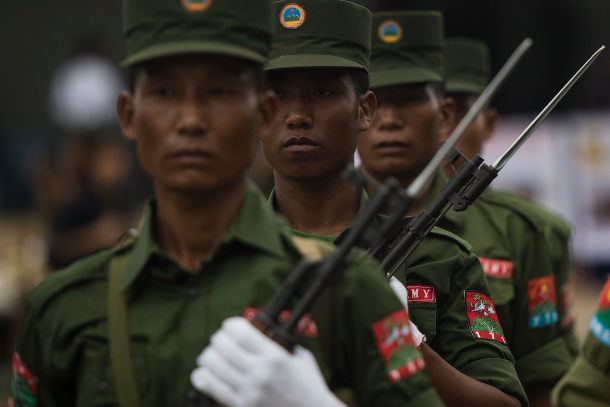

A file image of members of the United Wa State Army (UWSA) on June 26, 2017. The UWSA, a 30,000-strong militia known as Asia’s most heavily-armed drug dealers, boast their own autonomous territories on the border with China and have close links with Beijing. (Photo by Ye Aung Thu/AFP)

In recent months there has been a crackdown on religious practices by an ethnic militia force in a remote region on Myanmar’s mountainous border with China.

Churches in northern Shan State have been closed, crosses torn down and pastors and other Christian leaders detained by the United Wa State Army (UWSA).

On about Oct. 9, 100 Christians were released, but as many as 92 remained in custody, Christian leaders said.

The UWSA, the military wing of the United Wa State Party (UWSP), dominates the population of about 500,000 in the self-proclaimed Wa Self-Administered Division of Myanmar.

According to various researchers, the UWSA is the largest standing militia in the country with a force of up to 30,000 troops. The enclave has long been widely seen to be backed by China as is the implementation of the now intensified crackdown on religious practice.

The militia and its political arm are remnants of the Burmese Communist Party and retain very close links with authorities in China.

China is conducting a fresh campaign of internal repression of religion, but its motives in northern Myanmar are essentially economic.

It believes U.S. intelligence operatives have over many years been planted in Protestant missionary groups in the border region of majority-Buddhist Myanmar.

According to government census figures released in 2016, in Shan State there are nearly 570,000 Christians, the largest number of any state, amongst its 5.8 million residents.

Neighboring Kachin State, runs a close second, with 555,000 Christians in a population of 1.7 million.

China has for many years been involved in the conflict in Myanmar’s north, supporting the Kachin Independence Army and supplying it with arms, according to many reports, as well as widely seen ‘made-in-China’ munitions.

But in recent times, China has been more interested in resolving the conflict by taking an active part in peace talks between the two sides as it eyes embracing Myanmar as part of its extensive Belt Road Initiative (BRI) linking trade between Asia, Africa and Europe.

China’s economic interests in Kachin, and northern Shan State, where protestants vastly out number Catholics, include the acquisition of timber, opium for the drug trade, jade and rubies as well as cheap immigrant labor.

Communist Party-ruled China has also backed Myanmar military ethnic cleansing of Muslim Rohingyas in Rakhine State.

And China has had a hand in blocking aid to isolated internally displaced persons camps in Kachin State that can only be accessed via travel through China due to impassable mountains.

Myanmar’s major waterway, the Irrawaddy River, that starts about 50 km north of the Kachin capital of Myitkyina, is also the site of the controversial Myitsone Dam, a Chinese hydro-electric project that was halted in 2011 by then Myanmar President Thein Sein.

Front and center of Chinese interests is the long-mooted 1,700-kilometer China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) that got a green light from the Myanmar government in mid-September.

Myanmar and Pakistan are participants in the wider Belt Road Initiative that aims to build multiple land and sea trade routes that are part of a 21st century version of the ancient Silk Road, notes Sudha Ramachandran writing in the Chief Brief of the Jamestown Foundation think tank.

The CMEC is a sub section of the larger China-Myanmar Bangladesh-India corridor, one of six main planks of the BRI project.

It is planned to run from Kunming, the capital of China’s southern Yunnan province, and stretch from India and Tibet across the top of Southeast Asia to Vietnam.

The CMEC will cross the China-Myanmar border at Muse, in northern Shan State, and continue to Myanmar’s second biggest city and old imperial capital, Mandalay, in the country’s centre.

There it will split into two, with one arm running south-west to the port of Kyaukpyu in Rakhine State on the Bay of Bengal. The other arm is to run south to the former capital and commercial hub, Yangon.

In his Jamestown Foundation article, Sudha Ramachandran wrote; “The route to and from Kyaukpyu port runs parallel to gas and oil pipelines built by China that have been operational since 2013 and 2017, respectively. Although they were planned prior to the BRI’s rollout, like many Chinese projects overseas they have been re-branded as part of the Belt and Road.” Ramachandran said he was citing information obtained from the Chinese state-run news bureau Xinhua.

Already, in the country’s north, where militias led by the Kachin Independence Army have been fighting with the Myanmar military known as the Tatmadaw, there are concerns that local interests and environmental concerns may be secondary for Myanmar’s government.

The administration headed by formerly detained democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi in Nay Pyi Daw, is desperate to improve the country’s stuttering economy by bringing foreign investment.

The Rohingya tragedy and increased spotlight on the Kachin civil war have provided a timely economic opportunity for China, as investors from Western nations, lulled into what has turned out to be something of false dawn, are scaling back.

China is already the biggest foreign investor in Myanmar, buying more than US$20 billion in assets between 1988 and May of this year, according figures from the Myanmar government.

Suu Kyi’s administration has been openly concerned about the high levels of Chinese investment in Myanmar leading into a debt trap such as that experienced in other nations such as Venezuela and Sri Lanka.

Myanmar recently cut back Chinese investment in Kyaukpyu port by several billion dollars.

Conversely, Suu Kyi is desperate for peace through a dialogue process with dissident ethic groups and may see Chinese help in the north as the best option; China’s price is obvious.

It’s yet another difficult political tightrope she must walk, made none the easier by the ongoing conflict in Rakhine State that has resulted in hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas fleeing as refugees into neighboring Bangladesh.