On the morning of December 26, 2004, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra triggered a tsunami that inundated several coastal regions across South and South East Asia. The tsunami wave measuring 17.4 meters would become one of the deadliest natural disasters in the 21st century killing nearly 240 thousand people across several countries including Thailand, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and Maldives. (Indian Express, 2004) 1.4 million houses would be destroyed by the tragedy and over 5 million people displaced which would test national response capacities across South and South East Asia and highlight the need for cooperation amongst states in early monitoring and response.

This was a regional event leading to a regional response by the SAARC ( South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) to avoid massive casualties and prepare for such calamities in the future. Following the Tsunami, a Special Session of the SAARC Environment Ministers was held at Male on 25 June 2005 as a result of which, an expert group of the member countries planned to meet at Dhaka, Bangladesh to formulate a Comprehensive Framework in Early Warning, Disaster Management and Disaster Prevention. (SAARC) The SAARC Disaster Management Center (SDMC) was eventually set up on the premises of the Gujarat Institute of Disaster Management along with additional monitoring and early warning systems in Sri Lanka, Male and India. (MEA, 2017)

In most recent years, however, disaster management endeavours by the SAARC have lost momentum. A 2024 paper by the ORF concluded that SAARC mechanisms for disaster response only came into attention in the immediate aftermath of calamities and that momentum died down on such endeavours once enough time passed after disasters (Debates). Major steps in SAARC disaster relief plans only took place in the immediate aftermath of events. For example, the SAARC Agreement on Rapid Response to Natural Disasters (SARRND) was signed in 2011 only after the Pakistan flooding in 2010. Additionally, it was only five years later, in 2016, that the SARRND came into force following the Nepal earthquake in 2015 (Debates, 2024).

Background

The following paper outlines new methods of regional disaster and climate intervention by studying the period between 1992 and the present to see how the neo-liberal institution of ‘catastrophe bonds’ has helped regions in the US, Caribbean and Central America pool financial resources together to prepare for disaster and create better response measures. The paper also explores the possibilities of a parametrically triggered SAARC sovereign catastrophe bond to see how and if, they could serve as a means of sustained integration in climate and disaster cooperation in the region.

Climate-related issues and natural disasters are tricky to situate within the discourse of regional integration. It is because of this aversion of nation-states in the South Asian Region to sustain cooperation on such issues (Bose, 2024), that this paper follows a neo-liberal institutionalist approach to focus on the economic function of the catastrophe bond. Within neo-liberal institutionalism, states give up limited sovereignty to international institutions to achieve collective action goals. Here the state remains important and collaborative action elevates the status of the state as an effective gatekeeper between the domestic and the international (Hurrell 1995: 61-66).

In regional settings as well, neo-liberal institutionalism arises out of ‘inter-national policy externalities’ (Hurrell, 1995) which in this case is the increasing threat of natural disasters in South Asia due to climate change and the increased transaction costs imbedded in states taking singular action with individual deals with the UN, World Bank, international insurance companies such as Swiss Re to manage climatic catastrophe. Following this, the paper proposes that a collective SAARC ‘catastrophe bond’ could act as a collective institutional extension of the SAARC to encourage cooperation amongst states while limiting the impact on the sovereignty of states present in South Asia.

So what is a catastrophe bond? Also known as CAT Bonds, these are a special financial asset created in the United States in the wake of Hurricane Andrew which helped to reduce the risk exposure of governments and insurance companies during ‘catastrophic’ events. In 1992 Hurricane Andrew was the most expensive disaster to hit the United States, causing USD 27 Billion in damages out of which 15.6 Billion was paid out by insurance companies pushing eight such companies to failure and leading two into insolvency (Polacek, 2018).

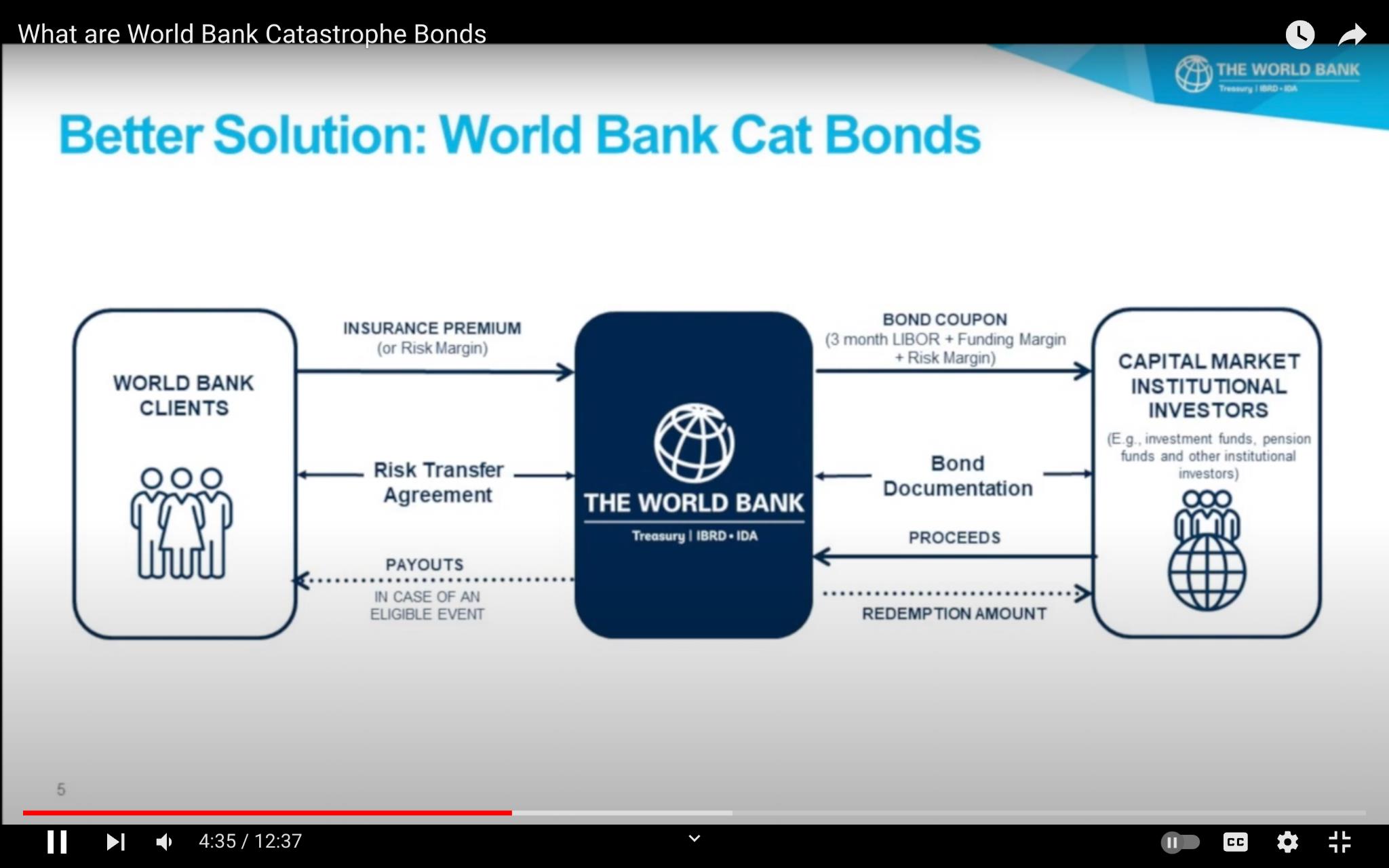

To improve the ability of insurance companies to fulfil their pay-out requirements and to collect capital, insurance companies started issuing bonds that regular investors could invest in through special-purpose vehicles (Polacek, 2018). The Special Purpose Vehicle could then invest the money into low-risk investments while the bond increased in value as more investors pooled into the bond. In the case of a ‘catastrophe’ measured parametrically, such as an earthquake ranking higher than 7.0, a hurricane with a certain barometric pressure, a tsunami wave of over 8 meters, or even a pandemic (based on the bond’s specifications), the bonds would ‘trigger’ leaving the insurer or the nation issuing the bonds free to sell the bond and use the capital to pay out dues during a catastrophe.

Historical Developments

Such bonds gained relevancy in the United States over the years as investors sought to invest in ‘uncorrelated’ assets that are not linked to the whims of the market but rather to the environment. The first state catastrophe bonds were issued in the US in the wake of Hurricane Andrew and the Northridge earthquake of 1994 leading to the creation of the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund and the California Earthquake Authority which helped ease spooked private insurance companies into reopening their firms with greater security in these states. Such bonds have since gained even more prominence especially after Hurricane Katrina hit the United States in 2005 which displaced Andrew as the most expensive disaster in US history (Polacek, 2018).

A number of regional and international organizations have expanded into the catastrophe bond markets since then. In 2014, the World Bank issued its first Catastrophe Bond through the Catastrophie Risk Insurance Facility which pooled together the risk exposure and resources of 16 Caribbean nations to provide them security against hurricane and earthquake risks (World Bank, 2014). The same bond paid a total of USD 20 million to Haiti and USD 1 million to Barbados in the wake of Hurricane Matthew in 2016 (CCRIF, 2016) Such sovereign bonds have increased in popularity since with over 30 CAT bonds issued by the World Bank since 2014.

Img: World Bank Management of Sovereign Catastrophe Bond (Source: World Bank)

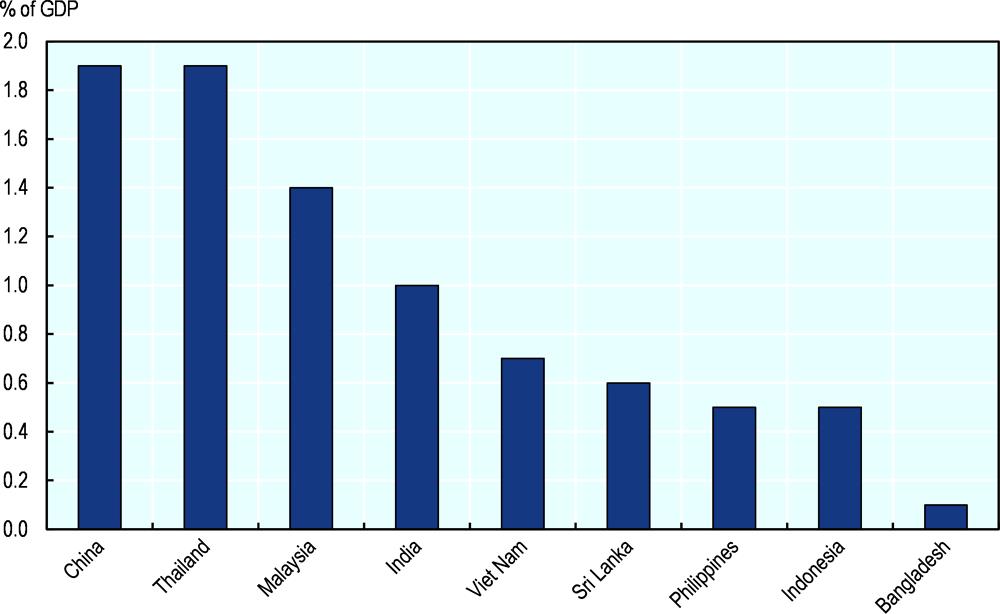

These bonds however remain underutilized in much of the developing world, especially in countries that require more intervention in risk mitigation. Several countries in the South Asian region lack insurance facilities. This creates heavy losses when such countries encounter climatic events such as floods, glacial lake outbursts, earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons and tropical storms. The worldwide protection gap, that is the difference between insured value and the economic losses has reached USD 378 billion with 78% of measured risks remaining uninsured (Evans, 2023) In the case of Asia, the following chart created by the OECD based on data from Swiss Re shows insurance gaps and risks faced by nations

Img: Insurance penetration measured as premiums as part of GDP within Asian Countries (OECD, 2024).

The sovereign CAT fund can come into help provide relief during catastrophic events since entities from developing nations are much less likely to be insured. So far however, the Phillippines is the only ASEAN country part of a CAT bond issued by the World Bank in November 2019, with no SAARC nations as part of such financial instruments. The OECD has pushed for a further adoption of CAT bonds within its member-states which are already highly served by private CAT bonds and outside its member states (OECD, 2024). Additionally, the Asian Development Bank too has proposed the Disaster Relief Bond (DRB) which is a specialized bond intended for CAREC countries (the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program (ADB, 2024).

When it comes to SAARC, creating a regional cat bond could come with great opportunities as well as challenges. One of the most recent cross-country insurance deals that the Indian government signed was in 2014 when after a visit of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bhutan, the General Insurance Cooperation of India helped Bhutan set ‘GIC-Bhutan Re’ to coordinate insurance in the country. (Economic Express, 2014) The chief managing director of GIC during the signing had stated the possibilities of further development of collective reinsurance facilities within SAARC countries stating:

“here is potential for more cooperation amongst the SAARC countries for managing their catastrophic risks efficiently. We need to work together and India will play a pivotal role in our pursuit to manage risks better ……all our countries are in a transitory phase and these catastrophe events put our growth and development several steps back.” (Economic Express, 2014)

Benefits and Risks

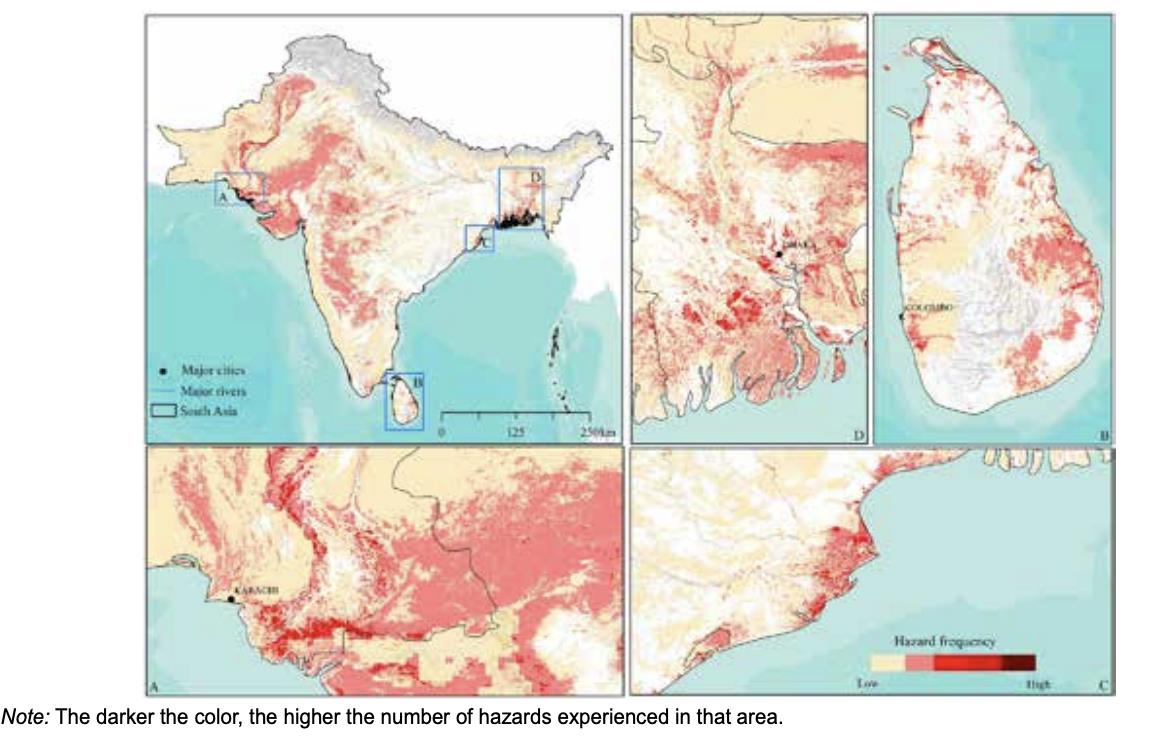

The creation of a regional catastrophe bond market would come with several advantages. For one, catastrophe bonds tend to work better following an increase in the region that is covered by the bond because of the diversification of risk and of the investors and stakeholders in creating the bond. A major glacial lake outburst for example is more likely to happen in India, Nepal or Pakistan within the SAARC region – securiting economic risks from such a catastrophe would work best with the addition of regions such as Bangladesh where other disasters are more likely to occur but at a different time. In a 2015 paper, Randey Dumm highlighted how the aggregation of geographic risk across states in the US would lead to reduced uncertainty and required reserves relative to total exposure of the least frequent and most severe incidents. (2015)

Img: Likelihood of five hazards with geographical indicators across (Amarnath et al. 2017: 18).

Additionally, a 2012 paper by Kevin Grove highlights how the Caribbean Catastrophic Risk Insurance Facility has benefited from ‘risk pooling’ allowing insurance companies and states to diversity their potential losses across a larger region and also allowing for states within the region to overcome financial exclusion and benefit from lines of credit that only existed prior for certain members. For example, 16 members of the Carribean were able to benefit from four companies (Paris Re, Swiss Re, and Hiscox, a Lloyd’s of London syndicate) and the Japanese government along with the World Bank (Grove, 2012) In a similar instance, SAARC countries could benefit from relationships from Indian, Russian markets as well as World Bank to create a broader spreadsheet of risks.

In terms of regionalism as well, the idea of a common catastrophe bond is an act of financialisation of biopolitics. It gives individuals a common vision of the future – because the value of these bonds to investors decreases with an increase in catastrophic events – it follows that environmentally friendlier policies would increase the value of these funds for investors across the region allowing space for cooperation amongst investors including banks, pension funds to cooperate to push for more environmentally friendly policies. (Grove, 2012)

CAT bonds, especially those that are ‘parametrically’ triggered, meaning bonds that are triggered when earthquakes reach a certain intensity, typhoons reach a certain wind speed, temperatures rise above a certain index or a pandemic reaches a certain infection rate – require for multi-party monitoring encouraging regional cooperation for monitoring encouraging the further development of initiatives such as the SDMC.

There are still difficulties as well as risks however in the the creation of such financial instruments. Grove also writes about how the CAT bond is a method of “the globalisation of a rationality of governing uncertainty through insurance which aligns “other” non-Western ways of being in the world with a Western financial capitalist rationality of governance”. (Grove, 2012) He proposes that the catastrophe bond is a method of financialization of the region as well as imposing a set of future-based calculations on to states which emphasise infrastructure and the functioning of the state.

With rising sea levels which pose a threat to Bangladesh – a sovereign CAT bond would trigger after levels reach a certain point – providing capital to the state and ensuring redevelopment. But this is also a shift away from the generationally occurring trend of migration away from places that face drought or harsh conditions. The neo-liberal institution then only guarantees a rationalized future of the state not of historically occurring trends of migration within the region.

Additionally, the CAT bond’s tricy use of triggers also comes into question. In September 2014 when hurricane Odile hit Baja in California, the event caused over USD 1 billion in damages – however, the Mexican Multi-Cat failed to trigger because the central pressure from the hurricane did not reach 932 millibars of pressure ( World Bank). A 7.9 earthquake could cause much the same damage as an 8.0 earthquake would but a parametric bond would not ‘trigger’ leaving developing nations within the region with little to rebuild. This also brings into question the influence that investing groups might have on meteorological and survey departments within the region. If it is in the interest of investing groups for a bond not to trigger – what is to say that in states already prone to corruption in South Asia – they cannot have an impact on how measurements are conducted – creating the scope of further anxiety and mistrust amongst states in the region.

Conclusion

The multiple technical challenges of the cat bond can be solved with proper planning and decision-making. Hybrid trigger mechanisms, and proper regulation by SAARC acting as SPVs can help create the correct the correct atmosphere for the proper functioning of the CAT bond. These bonds have appeared to be useful tools in recent years in providing much-needed catastrophe funding for major black-swan events in the US and the Caribbean and their popularity is rising with agencies such as the World Bank and ADB setting up regional agreements. Their benefits are lucrative for SAARC as well however, with what level of political dispensation, giving up certain sovereignty and also accepting the financialization of the future of states within SAARC would depend on how the region and its organizations imagine their possible futures.