by Ishaal Zehra 23 January 2020

Shaikh Hasina, the premier of Bangladesh, has long been accused of sacrificing her country’s interests and selling out to India by her political critics. This narrative intensified when the videos of Abrar Farhad, a student at the elite Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, went viral which showed how Farhad was tortured and finally killed by student wing of the ruling party after he wrote a Facebook post questioning the deals with India in October 2019.

Though most Bangladeshis love the Bollywood and like to travel to India for different purposes but somehow an anti-India sentiments run deep within a sizeable portion of the country’s population. And Farhad’s death, which triggered countrywide protests by students, academics and ordinary people alike, has intensified these sentiments and fuelled questions about Hasina’s alliance with India.

The matter has gotten worse for Hasina now after Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) has been espoused by India. There is considerable discord across the country over whether Hasina got well along CAA. The political leadership is now concerned that India may push Muslim immigrants deemed illegal under CAA across the border inside Bangladesh. The Bangladesh government had been worried of such nuisance since the National Register of Citizens (NRC) exercise was carried out in Assam (India).

At that time also, the Bangladeshi government made a demand to its Indian counterpart to give surety that NRC will not in any away push Muslim migrants into Bangladesh. At that moment, India had given a verbal assurance. However, it had refused to give it in writing, stating that the exercise was carried out as per directions of the Supreme Court. The Indian side referred to NRC exercise in Assam as an ‘internal’ matter saying the government was not in a position to give a formal assurance of anything. Just a day after, the Border Security Force pushed back at least 32 ‘Bangladeshis’ into no man’s land in Jessore, which the Karnataka police had nabbed a month earlier.

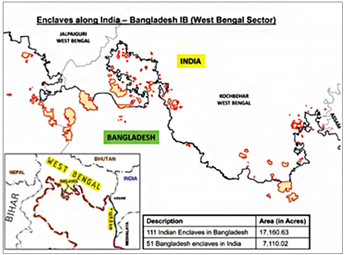

It was just 4 years back when on 6 June 2015, Bangladesh and India agreed for the historic swapping of enclaves between the two nations. Prime Minister Modi ratified the agreement during his visit to the Bangladesh capital Dhaka. In the presence of Modi and Bangladeshi Prime Minister, the foreign secretaries of the two countries signed the instruments of the exchange of enclaves and land parcels in adverse possession thus resolving the decades old border issues. The enclaves were exchanged at midnight on 31 July 2015 and the boundary demarcation was completed by 30 June 2016 by Survey Departments of the respective countries.

At the end of the exercise it was concluded that around 14,215 people (mostly Muslims) living in 51 Bangladeshi enclaves in India will become Indians. Similarly, some 37,334 people living in 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh will become citizens of that nation. Now some really intriguing questions arise after the CAA. India has already given a good share of people (37,334 to be exact) to Bangladesh already in the swap. Now after CAA what will be the fate of Muslims who were handed over to India as new entrants among those 14,215 people?

In India people fear that CAA will be used in conjunction with the NRC to deem minorities as “illegal immigrants”. Especially after many top BJP leaders including Home Minister Amit Shah have proposed that the NRC should be implemented across India after a successful pilot test in Assam where over 1.9 million applicants failed to make it to the NRC list. The NRC very clearly states that people, to remain an Indian citizen, have to produce a documentary proof that their ancestors were residing in India before March 24, 1971 – like the 1951 NRC or electoral rolls up to March 24, 1971. The next step is to produce documents for oneself to establish relationship with those ancestors. That is a tough ask in a country with a poor documentation culture and millions of people with meagre financial resources. And finally the left outs from the final NRC list will approach the Foreigners’ Tribunals and deemed as illegal immigrants will be ultimately send to detention camps or beyond borders as a worst case.

These enclave dwellers who have been living there for decades had one recurrent problem: that of identity crisis, says Brendan R. Whyte in his detail research on the issue. This, in turn, resulted in illegal migration where the dearth of reliable data has added to the complexity of the problem. Since Census had never been conducted in these areas, many created fake voter ID cards to work and more to avoid becoming an illegal migrant. This is all a result of India’s inability to implement the 1958 treaty with Pakistan, and her continued delay in ratifying a subsequent 1974 treaty with Bangladesh to exchange the enclaves. That the delays have been rooted in Indian internal politics is demonstrated, he underscores.

Bygone the past, now this non-seriousness on India’s part has become a matter of serious concern for Bangladesh. With a population of above 163 million (eighth most populous country in the world), Bangladesh has achieved 7-8 percent growth in recent times (partly thanks to the dire business conditions in Pakistan which led industrialist to shift their industries to Bangladesh). If remained as envisioned, the country will also be eligible to graduate to developing status from its Least Developed Country status by 2024. Amidst all going well, a wave of people being sent back from across the border after being branded ‘illegal migrants’ would be Bangladesh’s worst nightmare. That too at a time when Wajid has been compelled to accept nearly one million Rohingyas migrants from Myanmar.

Though Bangladesh has played well so far by balancing Chinese interests to progress and India’s desire to protect its influence in the region, but the uncertainty about the consequence of NRC in Assam and fear of forced pushbacks of Muslim migrants can harm Indo-Bangla ties irreparably. In Bangladesh concerns have grown in recent times over Modi policies in India, many of which not only destabilized the internal situation at home but also give rise to multiple regional problems and crisis. Sheikh Hasina is all troubled by having to explain to her people what Bangladesh has gained for the long list of favours she has done to India. Adding salt to the injuries is the no Indian support on the Rohingya issue, persecution of Muslims in India and oppression of Kashmiri Muslims at the hands of Hindu Rulers.

Regardless of its phenomenal economic growth, Bangladesh is an overpopulated country. If India continues with its NRC-linked pushbacks, it would certainly affect New Delhi’s bilateral ties with Dhaka. Worse, it would weaken Wajid’s grip on the country while spurring anti-India sentiments among its residents. Also, China might take advantage of this situation. And this certainly does not augur well for India at a time when other neighbours are already turning towards China.