by Aejaz Ahmad Wani 11/6/2018

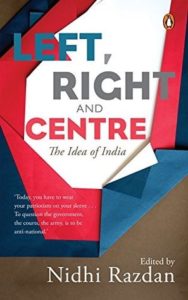

There has been much fuss about nationalism in India in the past few years. Catchphrases such as national/anti-national, anti-Hindu, anti-State, Sickularity, and intolerance have kept coming up in public sphere. This is nothing but a contestation on the Idea of India, whether the idea of India is reducible to a single category with certain attributes or whether intolerance is essential to the Indian tradition or is, in fact, there is such a thing as the Indian tradition at all. In recent times, these questions came up for discussion in several academic works which include inter alia, Sunil Khilnani’s Idea of India or Amartya Sen’s magnum opus The Argumentative Indian or a more recent work India Dissents: 3000 Years of Difference, Doubt and Argument by Ashok Vajpeyi. Towards that end, Nidhi Razdan’s debut book Left, Right, and Centre: The Idea of India is a stimulating work seeking to readdress these questions and make sense of the Idea of India in the context of some sweeping changes in the last seven decades. To talk about Idea of India, academically speaking, has never been short of a herculean task because it carries within itself a charge of essentialism and reductionism, no matter how best we sensitise and refine our arguments. Left, Right and Centre is not an academic work en masse. Academicians, politicians, activists, journalists and civil servants across the spectrum of ideologies have teamed together to jot-down thirteen essays (including the introduction), unfold their thematic and problematic of the idea of India, the way it has been perceived and understood and the ensuing political implications for India’s present and future as India completes seven decades of Independence. What I intend to do, in below headings, is to present, analyze and situate some key arguments made by various contributing authors to this book.

Introduction: The Rise of “The New Normal”

In the introduction to the book, Nidhi Razdan, the editor, begins with her early experiences in Kashmir in its halcyon days, when Kashmir was a ‘byword for religious tolerance’. Her ideal Kashmir, and therefore the idea of India, came crumbling down in 1989 with the emergence of the militant movement in Kashmir, and the consequent en masse exodus of Kashmiri Pandits therein. With the issue described as exhibiting communal undertones, it eventually became a plank of newly emerging nationalistic narratives. While all the communities in Kashmir have suffered the violence perpetrated by the State and non-state actors, there has been an increasing urge to weigh up the pain of community over the other, thus, justifying one sort of pain over the other. For Razdan, it is the rise of neo-nationalism or simply new forms of nationalism which are culturally defined and narrowly imagined, that compartmentalizes our social senses and doesn’t allow us to look beyond this narrow prism.

The ‘new normal’ as Razdan calls it, entails the emergence of narrow discourses on nationalism that situates every act in a ‘national’ and anti-national’ dichotomy, even those acts which are unrelated to it. This discourse generates its own ‘alternative facts’ about India to legitimise its claims. Razdan notes some of its peculiarities of such a discourse that has percolated politics, media, and even courts. First, it squarely exempts certain institutions from any sort of criticism, for example, army, thus, setting a discourse of what can and cannot be said in the public realm. This was evident in the soldiers who, after having had released a series of confessional statements about corruption in the army, were abused and verbally harassed. Secondly, it valorises war as the only solution to every sort of problem, especially with Pakistan. Thirdly, it is reductionist, that is, it reduces every act into a dichotomy. Four, it gives more importance to nationality than humanity. Last but not least, it targets educational institutions so as to find its way there.

Razdan reemphasises Tagore’s prophetic warning about the pitfalls and moral degeneracy of nationalism as we continue to grapple with it even today. The only way out, Razdan argues, is to reassert our belief in a democracy wherein every institution, including army, is called into question whenever the need be. This is only possible when dissent is given a space to ease the nervousness that represents our nationalism today. Razdan’s diagnosis of our times is correct, yet she refrains from taking names, of those who sponsor such discourses. This could have been a bold diagnosis from a brief account of those who spread nervousness about our collective existence.

In Search of a Middle Ground

Shah Faesal’s essay On the Wrong Side of History is all more about his childhood days, personal struggles, the killing of his father and the perpetual fear that doomed Kashmir in the 90s. This essay, however, makes some key observations on the Kashmir conundrum. To begin with, Faesal shows how difficult it is to take a middle ground, or what he calls being a fence-sitter, in the turmoil-ridden Kashmir. Faesal laments the way Kashmiris are dying while the two countries are settling the unfinished business of history between them. But he questions the way people in Kashmir indulge in selective outrage by condemning one type of violence, especially committed by the State while condoning other types of violence, particularly committed by non-state actors. Here Faesal makes a somewhat contentious point. He writes that the inability of people to speak out when one is killed by militants essentially “makes an Ikhwani (pro-government militia) out of an innocent fence sitter”. Faesal perhaps fails to recognize that Ikhwanis were ruthless surrendered militants who indulged in mindless violence. The Indian government in the 1990s capitalized the internal fault-lines in Kashmir and mobilized, funded and sponsored, mostly, surrendered militants who were ruthless in perpetuating violence across Kashmir. Very frequently, Ikhwanis killed innocents, collected ransom, siphoned-off resources, all followed from the power-shift into their hands. If every innocent fence-sitter targeted by militants necessarily become Ikwanis, as Faesal claims, then, he has to justify why every other innocent fence-sitter targeted by the State shouldn’t join the other side, as a corollary. Faesal, thus, fails to nurture a sustainable middle ground by necessarily rationalizing one sort of violence over another, an end he has been defending for quite some time now. Faesal, nevertheless, recognizes non-violence and inclusiveness as prerequisite mainstream strategies for the resolution of the conflict in Kashmir.

The Coma of Civilization

Much like Razdan and Faesal, Rahul Pandita’s essay narrates his side of the story of Pandit exodus from the Valley, but unlike them, he doesn’t invoke Kashmir’s syncretic past, Kashmiriyat, or its recession in the 1990s. In Pandita’s two accounts, of the pre-1990 and the post-1990 Kashmir, there isn’t much difference, for he claims that it was not the first exodus that ‘his community’ had faced but several, spanned back across centuries. The connecting thread between Pandita’s ‘idea of Kashmir’ and ‘Idea of India’ has been the similarity of Hindu gods. Using V.S. Naipaul’s imagery of ‘lost India’, Pandita underscores that the idea of Kashmir, and for that matter, India, have been assaulted several times, ostensibly by the Muslim invaders, and just as Indians have developed collective amnesia of those assaults, the Pandit mass exodus was yet another assault in the series that was eventually subsumed under what he calls “Coma of Civilization”. For Pandita, the talk of Kashmiryat is just like a sweet pill that is said to ease the ‘pain’ of the wrongs committed by a particular community, therefore, an attempt to expedite the process of collective amnesia. Pandita’s overarching claim is quintessential rightist position, Hindu or Islamic, that ‘’our civilization” has been under attack and that we need to pay “heed” to it, to restore it, to purify it and bring back its “lost glory”. Towards the end of his essay, Pandita reminds us that people of India have rightfully voted into power a man who claims to ‘heal’ the ‘wounded civilization’, to restore the “equilibrium of Dharma”.

Quest for the Dignity of Other Sexualities

The debates on Idea of India are often predicated on the issues pertaining to religious and cultural identities, to the total exclusion of sexual identities, their dignity and their rights. Gautam Bhan’s essay The (In)Dignity of Our Sexualities is an unprecedented attempt to unfurl the issue of sexualities in the otherwise frozen debate. As a gay activist, Bhan highlights the struggles of other sexualities, LGBT, in India, for recognition, legal and societal. He notes that their struggle for the right to dignity is not confined to the legal sphere only, it is more than that, it is a resistance against what is described as normal, against the Othering of people in India.

Bhan, then, turns to the much-touted claim that cities in India, as elsewhere, are essentially cosmopolitan, inclusive and tolerant, that sustains a shared space for every sort of dissent and allows open views. Unfortunately, however, Bhan finds India’s cities exhibiting “patterns of entrenched hierarchies”, where Othering of some is a norm, where ‘people’ doesn’t mean all and sundry but chosen categories, where society retains caste endogamy, and to use his words where “gates rather than streets mark our urban forms’’. Therefore, Bhan’s idea of India constitutes a space which provides and protects sexual equality and dignity of LGBT community. For him, the aim of the struggles of sexualities is not just to legalize other sexes in India, but to challenge the roots of prejudice and intolerance in communities, societies towards other possible forms of life.

Through the Past into the Future

Yashwant Sinha’s essay Through the Past into the Future presents a right to the centre reflection on what the idea of India has been and where it is heading now. Sinha often brings up issues that normally remain moribund in the Right-wing party, the BJP. In this essay, Sinha views India as an ‘eternal country’ that has survived the onslaught of history, keep up its unique identity and provided an epitome of assimilation. Sinha engages in essentialism and describes Indians as essentially peace-loving, slow-moving or gradualists, non-violent, indifferent, tolerant, features that have helped them to not just accommodate changes and people, but also to fight their freedom struggle non-violently and reject non-violence as an acceptable strategy. Sinha, however, doesn’t discuss if same essential features, if there truly are, also prevent them from fighting caste and gender oppression, poverty, corruption and criminalization of politics. While much of this essay is devoted to discuss the political history of India, the conclusive paragraphs do advance an important development of our times. Sinha notes that apart from several deformities plaguing Indian politics; the even worst is the rise of neo-conservative tendencies, “liberalism on the economic front and sectarianism in politics”, both religious and caste types. Sinha continues to be one of the most reasonable and self-critical voices from within the Right.

Anglo-Indians in the Idea of India

Darek O’Brien’s essay Addressing Nellie narrates the glimpses of experiences of the Anglo-Indian community in India after Partition, their accommodation, decline and a subsequent emergence after the 1990s. Darek’s petite essay is emotionally charged. He narrates the Partition saga that divided two sons of a mother, Nellie, great-grandmother of Derek, one decided to live in India and other in Pakistan. It is not until 1984 when Darek’s family reconnect with their relatives in Pakistan and find most of their relatives having converted to Islam, of course giving up in pressurized and sometimes hostile ambience there. Darek’s implicit comparison between the social and political conditions in both countries that minorities get to face reflects his idea of India. For him, unless a happy society is created, with opportunities, hope and aspiration, no country can have a happy minority. India, for Darek, thus, represents a pluralistic country which embraces every shade of difference with dignity, freedom notwithstanding it’s all limitations.

From Federation of Communities to Zone of Freedom

Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s essay India: From Identity to Freedom is a gripping academic reflection on the theme. It challenges the conventional contestation in India normally poised between secularism and communalism, and finds it rather in between two different ideas of India; India as a “Federation of Communities” and India as a “Zone of Freedom”. For Mehta, several of the pathologies in Indian politics can be attributed to the tension between them. By FOC, Mehta means a “bewildering mosaic of communities of all kinds…that have shown a remarkable ability to incorporate diversity.” But this federation, Mehta argues, is predicated on a weaker conception of toleration, one that doesn’t ensure freedom and dignity and superimposes identities.

Conventionally speaking, diversity is celebrated in India or maybe constitutes India per se. For Mehta, however, such a celebration also becomes an insidious pathology too. Firstly, diversity itself cannot be a panacea to the problems of diversity, we need to find its limits. Because such an invocation is misleading for it places no value on individual freedom but all value on diversity of cultures. Subscribing to a certain liberal critique of Communitarian argument, Mehta notes, it is the enrichment of the former that will certainly lead to the enrichment of the latter and not vice versa. Secondly, this Diversity Talk is attuned only to what he calls –segmented or hierarchical toleration, one which presumes walls between communities. The problem is that, Mehta explains, following this conception, “there can be no incompatibility between celebrating the diversity of the nation and not renting housing to a Muslim just because he is a Muslim”. Thus, our moral discourse is essentially misleading. Third, such a conception of diversity is comfortable with philosophical non-engagement. Mehta laments that despite the historical engagement and exchanges between Islam and Hinduism, our public discourse is so compartmentalized that we don’t talk about it anymore. Invoking the works of Iqbal and Aurobindo, Mehta writes;

“it is almost as if, except for a cursory reference to idolatry, Hindu thought doesn’t exist for Iqbal; and Islam doesn’t for Aurobindo’’

Furthermore, he argues that there has been serious engagement between Islam and Hinduism, exemplified particularly by Dara Shikoh’s works, that were driven by the quest for knowledge rather than a desire to add identities. Forth, our conception of toleration helps institute what he calls the tyranny of compulsory identities, which entails the state provides no choice to the individuals to define or redefine their own identities. Once classified into a category freezes your identity forever and there is no escape from it whatsoever. He writes; “in the name of breaking open prisons, they imprison us even more”. This leads Mehta to argues further that the real battle in India is not played between majorities and minorities, but “between forces and institutions in each community that want to bend the arch of history away from freedom and equality in the personal space”. These forces and institutions include religious boards, Hindutva ideologues and some secularists who take this discourse as a hostage. What India requires is not a new conception of Indian identity that emphasises pluralism and compositeness but a social contract over how we respect and deal with those with whom we disagree about India’s identity, to find the ways of acknowledging the difference.

In highlighting the contradictions in FOC, Mehta pitches for a shift from FOC to the idea of India as a Zone of Individual freedom, premised on the individual as a unit of moral justification rather than its commitment to individualism or an idea of ‘unencumbered self’. This conception doesn’t set goals for individuals, but merely makes them an outcome of ‘free choice’. In short, Mehta’s cardinal argument here is that once individual freedom is honoured, it will ensure and promote the communities rather than the other way round. That such a conception doesn’t rule out differentiated rights but rather ensures that their function is to honour freedom.

Idea of India and its Dying Environment

Imagine an idea of India where each of its identities gets its due expression and protection but where its environment is dying fast, pollution eating up each of its resources! Sunita Narian’s essay somewhat invokes a similar imagination. For her, our idea of India is increasingly emphasising unbridled economic growth and consumerism but doesn’t ask whether such a growth is inclusive and sustainable. She shows how increasing accentuation of economic growth based on trickle-down economics is failing fast to even benefit the rich, let alone the poor; destroying the environs; culminating into a climatic catastrophe across the word. In India, she notes, owing to our obsession with economic growth, the air quality is dipping, rivers dying, and rain and temperature showing alarming variance and it is poor Indians who are worst hit. With rising social costs, and increasing unemployment owing to automation, poor become the face of this global tragedy. She argues that it is the time now that we realize what we are aspiring in our search for the Utopian India based on economic growth is actually dystopia and recommit to the idea of Indian built on the concept of justice, inclusive and equitable economic growth.

India as a Space of Shared Value

Tharoor’s essay The Idea of an Ever-Ever Land acknowledges the immensity of diversity in India making it impossible to pinpoint what the idea of India is, for every idea of India stands contradicted by another idea. Tharoor concedes that the very idea of India is inherent in its civilization and as time passed, it incorporated various other cultures within it, with which it now shares a sense of history. This makes India An Ever-Ever Land. But what sustains this myriad of cultures is a pluralistic democracy, and modern liberal values of liberty, equality and fraternity, values that are enshrined well in our Constitution. Democracy provides a space to every difference. The constitutional values don’t make Indian nationalism dependent on any particular indices of identity, culture, caste or religion. It allows the possibility of multiple but complementary identities. Tharoor Writes;

“My idea of India celebrates diversity: if America is a melting pot…..then to me, India is a thali, a selection of sumptuous dishes in different bowls. Each tastes different and does not necessarily mix with the next, but they belong together on the same plate and they complement each other in making the meal a satisfying repast”.

Tharoor admits the challenges posed by various divisive forces to our shared idea of India and warns us that any attempt to define Indianness in exclusive and divisive terms will be dangerous for India’s future.

Conclusion

Apart from the essays distilled above, there are other essays that reflect upon this theme but seem rather simplistic historical accounts. For instance, Chandan Mitra’s essay simply traces the political history of the Right in India to make sense of its hegemonic present. Similarly, Shabana Azmi’s essay tries to understand factors that sustain the unity of India. Nidhi Razdan’s book serves several purposes. To begin with, it is a timely reflection on this messy issue and certainly clears out much confusion that looms around it in India today. Second, as stated earlier, it is not purely an academic work. Barring a couple of essays, it is a smooth-tongued work that avoids academic sophistication and mechanistic argumentation making it more reader-friendly. Third, it brings contesting reflections on the Idea of India on a single table, thereby, enabling readers of every sort to evaluate the issue more comprehensively and meaningfully. As a post-script to this essay, one, perhaps, feels that this book should have carried few more Right essays than it presently has, to make the debate more nuanced and balanced.